Top Software Supply Chain Security Vulnerabilities Explained

Introduction: When was the last time you audited the dependencies and build processes behind your software? The ugly truth is that every open-source library you npm install, every Docker image you pull, and every script in your CI pipeline is a potential attack vector. Modern development heavily relies on external components and automation, which has opened the door to a new breed of software supply chain threats. In fact, supply chain attacks have skyrocketed – Sonatype reports discovering over 700,000 malicious open-source packages since 2019. And just recently, a single npm maintainer’s account compromise led to 18 widely-used packages being backdoored with malware, putting billions of weekly downloads at risk. These incidents underscore why development teams, DevOps engineers, and DevSecOps practitioners need to care about software supply chain security now more than ever.

A “software supply chain vulnerability” refers to any weakness in the processes or components that go into building and delivering your code – from third-party packages to build tools and CI/CD workflows. Attackers have realized they can compromise countless downstream applications by poisoning one upstream component. The rest of this post breaks down nine of the most critical and commonly overlooked software supply chain security vulnerabilities. For each, we’ll explain how it works, how it might manifest in real projects, the risks it poses, and how to mitigate it. We’ll also include Aikido Security callouts to illustrate how modern security tools (like Aikido’s dependency scanner, secrets detection, SBOM analysis, and CI/CD scanning) help identify or prevent these issues.

The Top 9 Software Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

1. Malicious Typosquatting Packages

One of the simplest supply chain attacks is typosquatting – where attackers upload malicious packages to registries (npm, PyPI, RubyGems, etc.) using names nearly identical to popular libraries. The goal is to trick developers (or their automated tools) into installing the impostor by mistyping or misidentifying the package name. For example, threat actors have impersonated packages like typescript-eslint on npm with names like @typescript_eslinter/eslint, which racked up thousands of downloads before detection. These counterfeit packages often contain hidden malware: they might run a post-install script that drops a trojan or exfiltrates data. In one case, a typosquat of a code formatter silently installed a malicious executable (prettier.bat) that persisted on Windows startup.

How it works: Attackers observe popular libraries and create a malicious package with a name that’s a common misspelling or variant. This could be as subtle as a missing hyphen (types-node vs the legit @types/node) or a different namespace. They publish these packages to the public repository with some enticing version number or description. Unsuspecting developers might typo the name or choose the wrong package in a hurry, thereby pulling in the malicious code. Automated scripts and CI systems are equally vulnerable if the package name is wrong by even one character.

Risks: Once installed, the malicious package runs with the same privileges as your application build. It can steal environment variables (secrets), install backdoors, or download second-stage malware. In enterprise environments, a single poisoned dependency can spread to many applications or services. These attacks are insidious because developers often don’t realize the mistake until after damage is done. The trust we place in package managers can be abused to execute code on developer machines or CI runners, potentially leading to stolen credentials, data exfiltration, and compromised servers.

Mitigation: To defend against typosquatting, developers should double-check package names and only install libraries from official or verified sources. Enable 2FA on package registry accounts (to prevent attackers creating look-alike scopes or profiles). Many ecosystems now offer package signing or verification – use these features to ensure authenticity. Incorporating automated tooling is also key. For instance, a dependency scanner can flag suspicious packages or names that don’t match known official libraries. Using a “allow list” of approved packages or package URL (pURL) identifiers can prevent installing something that just looks right. Educate your team to be vigilant when adding new dependencies.

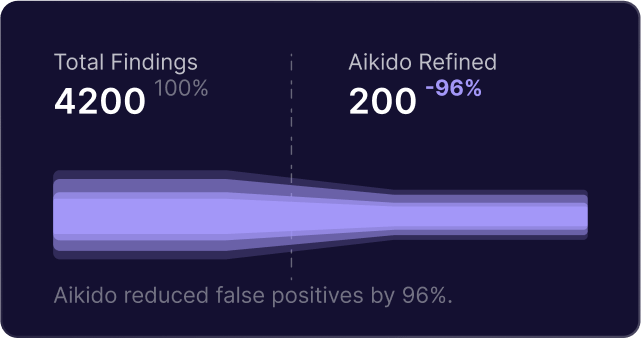

Aikido’s dependency scanner can automatically detect known malicious packages and typosquat variants before they make it into your build. For example, Aikido’s SafeChain feature blocks packages that are brand-new or known to be malicious, preventing that dangerous npm install from succeeding. By scanning your project’s manifest and lockfiles, Aikido helps ensure that react-router is actually the real React Router – not a malware impostor. This kind of proactive scanning and policy (e.g. requiring packages to be a certain age or popularity) can stop typosquatting attacks early, keeping your supply chain clean.

2. Dependency Confusion (Internal vs. Public Package Mix-ups)

Dependency confusion, also known as a namespace confusion attack, is a clever exploit against organizations that use a mix of private (internal) and public packages. It takes advantage of how package managers resolve names: if an internal package name accidentally matches a package on the public registry, an attacker can publish a public package with the same name and a higher version to “confuse” the resolver. The result? Your build system might pull the attacker’s code from the public registry instead of your intended internal package. This attack vector was famously demonstrated by security researcher Alex Birsan in 2021, when he breached dozens of major tech companies (Apple, Microsoft, Tesla, etc.) by uploading rogue packages matching those companies’ internal project names.

How it manifests: Suppose your company has an internal npm package called @acme/widget-core at version 1.3.0, hosted on a private registry. Your project’s package.json requests @acme/widget-core. If an attacker publishes @acme/widget-core version 9.9.9 to npm (public) and your build isn't locked to the private source, the package manager might fetch the 9.9.9 from the public registry (thinking it’s a newer release). The malicious package could contain a postinstall script that runs automatically on install, achieving remote code execution in your build environment. In CI/CD pipelines, this is especially dangerous: the code runs on build agents which might have access to sensitive environment variables, source code, and deployment keys.

Risks: Dependency confusion can lead to immediate compromise of the build or dev environment. The malicious payload could exfiltrate secrets (API keys, tokens, credentials) or inject backdoors into the built application without any code in your repo changing. It effectively bypasses traditional code review or vulnerability scanning of your repo because the harmful code lives in a dependency you unknowingly pulled. The impact can be severe: attackers might gain lateral movement into company networks (if build servers are compromised) or insert malicious logic into software delivered to customers. It’s a widespread threat surface given how common internal package naming collisions can be.

Mitigation: Preventing dependency confusion involves a mix of technical controls and hygiene. Always explicitly scope your private packages and configure your package managers to prefer private registries for certain namespaces. Package manager settings like npm’s @acme:registry in .npmrc or pip’s index settings should be used to lock dependencies to the intended source. Use strict version pinning and lockfiles so that even if a higher version appears elsewhere, your build won’t automatically take it. Monitor public package registries for any of your internal package names accidentally leaked (attackers often guess these via public repo mentions or config files). Many organizations now use artifact repositories as a proxy, so that only approved packages are fetched. This creates a gate where unknown packages (even if name matches) won’t be pulled in. Finally, regular audits of dependency configs and generating an SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) can help spot if an unexpected external package snuck in.

Aikido’s platform is equipped to catch dependency confusion scenarios. For example, Aikido’s dependency scanner cross-references your package manifest against both public and private sources. If it sees a dependency name that exists on npm/PyPI but is supposed to be internal, it will raise an alert. Aikido can also enforce policies to only allow certain registries or enforce namespace controls, ensuring your builds don’t accidentally reach out to untrusted sources. Through SBOM analysis, Aikido provides visibility into exactly which package version and source was used in a build – making it easier to detect and prevent a stray public package from sneaking into an internal app. In short, Aikido can help ensure that what you build is exactly what you intended to build, with no surprise code.

3. Hijacked Libraries and Protestware (Compromised Maintainers)

Not all supply chain attacks come from new, fake packages – sometimes trusted packages turn malicious due to maintainer account compromises or intentional sabotage. When an attacker gains control of a legitimate package (via phishing the maintainer, stealing credentials, or exploiting lax security), they can publish a trojanized update that consumers download thinking it’s a normal new version. This happened in September 2025, when a maintainer known as “qix” was phished and attackers pushed malicious updates to 18 popular npm libraries, including debug, chalk, and ansi-regex. Those libraries collectively had billions of weekly downloads, meaning the impact of just two hours of malicious code availability was enormous. Another scenario is “protestware,” where an open source maintainer intentionally alters their library (e.g., to display political messages or worse, to sabotage systems in certain countries). In both cases, the package that you’ve trusted and used for years can suddenly become a weapon against you.

How it works: Attackers target high-impact packages – often those deep in dependency trees so developers might not notice an update. Common tactics include phishing maintainer login credentials (as with the npm incident above) or leveraging OAuth/token leaks. Once they have access, they publish a new version containing malicious payloads. These payloads can be quite sophisticated. In the 2025 npm attack, the injected code was a crypto wallet stealer that only activated in browser contexts. Other backdoors might collect environment data, open reverse shells, or encrypt data (ransomware style). Because the version is still semantically valid (e.g. 4.4.2 to 4.4.3), and often the package still works normally aside from the hidden malicious side-effect, it can propagate widely before detection. Users typically only discover the compromise when security scanners flag unusual behavior or when the community/public registries announce it.

Risks: The obvious risk is that you’re running malicious code under the guise of a trusted dependency. This can lead to theft of sensitive information (the npm incident’s malware targeted crypto transactions, but it could just as easily target authentication tokens or customer data). It undermines the integrity of your software – even if your code is secure, the compromised library can completely subvert it. Additionally, these attacks erode trust in the ecosystem; teams might freeze updates (missing out on legit fixes) out of fear. In a worst-case, a widely used compromised package can serve as a backdoor into many companies at once, as it essentially creates a botnet of all installations phoning home to the attacker.

Mitigation: Defending against hijacked packages is tricky since it’s a betrayal of trust. However, there are best practices to limit the blast radius. Treat dependency updates with healthy skepticism: review changelogs and diffs of new versions, especially for core utilities that don’t usually update often. Utilize automated malware scanning on new package versions – some tools analyze package behavior (like detecting if a new version suddenly starts making network calls or reading system info). Pinning versions (and not auto-upgrading to latest without review) can buy time to observe community reports. Use of lockfiles and checksum verification (as supported by npm, pip’s hash checking mode, etc.) can ensure you’re installing exactly what you expect – and consider enabling 2FA and verification on your own packages if you publish any. From a process standpoint, maintain an inventory of your dependencies (an SBOM) so you can quickly identify if you use a package that gets compromised and need to respond.

Aikido’s continuous dependency monitoring shines here. Aikido’s scanner doesn’t just check for known CVEs – it also looks out for suspicious package behavior and known malware signatures in dependencies. For instance, if a new version of requests on PyPI suddenly attempts to open network connections on install, Aikido would flag that anomaly. Aikido integrates threat intelligence (including feeds of known compromised or hijacked packages) so it can warn you if a dependency in your supply chain is reported as sabotaged. Additionally, with Aikido’s AutoFix and vulnerability feeds, if a malicious version slips through, the platform can recommend and even automatically open a fix PR to revert or upgrade to a safe version. The key is speed – Aikido helps detect these incidents early and automate your response, reducing the window of exposure.

4. Exposed Secrets and Credentials in Code or CI

It’s often said that credentials and secrets are the keys to the kingdom. In the context of supply chain security, leaked secrets (API keys, cloud credentials, signing keys, etc.) can be as dangerous as any malware. Why? Because if an attacker finds a valid AWS key or CI/CD token in your GitHub repo or build logs, they can directly use it to infiltrate your systems or poison your pipeline. Leaked credentials are a leading cause of breaches – according to the Verizon Data Breach report, 22% of breaches in 2024 were caused by exposed credentials. In supply chain terms, secrets in source code or config can allow attackers to publish rogue code (using your credentials), access private package registries, or push malicious artifacts into your deployments.

How it manifests: Secrets can leak in many ways. A developer might accidentally commit a .env file with database passwords to a public repo. Or a CI/CD pipeline might print a sensitive token to logs that are world-readable. Even more subtly, an attacker who gains initial access might search your codebase for hardcoded keys. Once obtained, these secrets can be used to impersonate your accounts. For example, an AWS key could let an attacker push a poisoned container image to your private ECR registry which your deployment then pulls. A GitHub personal access token could allow an attacker to commit code to your repo or tamper with your releases. In CI pipelines, if an attacker gets a hold of credentials for CI or cloud, they can effectively bypass normal code review and directly insert malicious components or infrastructure.

Risks: The direct risk is unauthorized access. Exposed cloud keys might lead to infrastructure breaches or data theft. Exposed package registry credentials could let an attacker publish a new version of an internal library with malware (another route to the hijacked package scenario). In CI, leaked tokens might let attackers alter build configurations, retrieve secrets from vaults, or intercept artifacts. Essentially, secrets are like skeleton keys: once the attacker has them, they can often move through your systems without needing to exploit a software vulnerability. This can result in anything from a full production environment compromise, to attackers silently altering artifacts (e.g., swapping out a binary in a release pipeline with a backdoored one). These scenarios are part of supply chain attacks because the integrity of the software delivery process is broken by stolen trust.

Mitigation: The best mitigation is don’t leak secrets in the first place. Easier said than done, but there are concrete practices: Use secret scanning tools on your repos to catch API keys or passwords before they get committed. Git providers like GitHub have integrated secret scanning – enable it. Never hardcode sensitive creds in code; instead use environment variables or secret management services (and ensure your repos don’t contain those values in config files). In CI/CD, mask secrets in logs (most platforms have options to prevent printing of secret env vars). Regularly rotate keys so that if something does leak, it’s only valid for a short window. Employ the principle of least privilege: a leaked token that only has read access is far less damaging than an admin token. For any high-privilege keys, enforce multi-factor or IP restrictions if possible. Monitor for usage of secrets – e.g., if a key that should only be used by your app starts being used elsewhere, that’s a red flag.

Aikido’s secrets detection feature is designed to catch exposed credentials early. It scans your code, config files, and even CI pipeline definitions for patterns that match API keys, private keys, tokens, and more. For instance, if someone accidentally commits a GitHub Personal Access Token or an AWS secret key, Aikido will flag it immediately, allowing you to purge and rotate it. But detection is just part of the story – Aikido can integrate with your CI to fail a build if a secret is found, preventing accidental deployment of sensitive info. It also helps maintain an inventory of what secrets are where, complementing your use of vaults or secret managers. By integrating secrets scanning into the development workflow (IDE plugins, pre-commit hooks, CI checks), Aikido helps developers keep credentials out of repositories and pipelines, cutting off one of the easiest paths attackers use in supply chain breaches.

5. Insecure CI/CD Pipeline Configurations (Pipeline as Attack Surface)

Your CI/CD pipeline is effectively the assembly line of your software factory – and if it’s misconfigured or insecure, attackers can tamper with everything coming off that line. CI/CD systems (like GitHub Actions, Jenkins, GitLab CI, etc.) often have broad access: they pull code, integrate dependencies, run tests, push artifacts, and even deploy to production. This makes them a juicy target. Common pipeline security issues include overly broad access permissions, lack of isolation, and using default insecure settings. A recent analysis found that about 23.8% of software supply chain attacks exploit CI/CD build vulnerabilities, underscoring how pipeline security is now a major front. In practice, we’ve seen incidents where attackers exploited CI misconfigurations to move laterally. For example, a misconfigured Jenkins server open to the internet or a CI job that inadvertently runs untrusted code (e.g. building PRs from external contributors without sandboxing) can lead to a compromise.

How it manifests: One scenario is over-privileged pipeline runners. Imagine a CI agent that has admin access to your cloud or is allowed to deploy artifacts directly. If an attacker can insert themselves into the CI (through a code injection, a compromised credential, or exploiting the CI tool), they now effectively have the “keys to the kingdom” – they can inject malware into builds, or even use the CI agent to run commands in your infrastructure. Another scenario is not enforcing checks on incoming code: e.g., a malicious pull request that contains a CI configuration change to exfiltrate secrets or skip tests could slip through if code reviews are lax. Also, many CI pipelines mount secrets (like signing keys or deployment credentials) as environment variables. If the pipeline is not configured to restrict who can trigger builds or what code runs, those secrets can be stolen by attackers who manipulate the build. For instance, some default setups might allow forked repository PRs to run the main CI with access to secrets – a known dangerous setting that can leak secrets to malicious contributors.

Risks: The CI/CD pipeline, if compromised, gives an attacker a direct path to compromise software at build or deployment time. This could result in unauthorized code being shipped to production or users (imagine malicious code added during the build that never existed in source control). It can also lead to widespread data exposure; CI systems often contain logs or artifacts with sensitive info. An insecure pipeline can be abused to pivot elsewhere – for example, if your Jenkins server has network access to internal services, an attacker who breaches Jenkins can then exploit those services. Essentially, a vulnerable CI is an entry point to both your software product and your infrastructure. It’s also an often overlooked area – dev teams focus on app code security but might not scrutinize the pipeline with the same rigor.

Mitigation: Securing CI/CD pipelines requires treating them as production assets. First, lock down access: ensure your CI system isn’t openly accessible, use VPNs or IP allow-lists, and require authentication for triggering sensitive jobs. Apply the principle of least privilege to pipeline credentials – for example, if a build job only needs push access to an artifact repository, don’t also give it cloud admin rights. Use separate credentials for separate jobs/stages. Second, sanitize inputs: for publicly facing workflows (like open-source projects where anyone can open a PR), use isolated runner environments with no secrets, or require manual approval for running untrusted code. Many CI platforms let you mark secrets to not be available to forked PRs. Enable audit logging on your pipeline: know who changed what in build configs. Another key practice is to pin your CI dependencies – if your pipeline uses build containers or third-party actions/plugins, pin them to specific versions or hashes (avoiding “latest” tags) to prevent an attacker from swapping something out (more on this in the next section). Regularly update your CI software and plugins, as vulnerabilities in CI tools themselves do emerge. Finally, consider using ephemeral isolated runners for each build (where feasible) so that one compromised build doesn’t persist a foothold for the attacker.

Aikido provides CI/CD security scanning that helps audit your pipeline configurations for best practices and potential misconfigurations. For instance, Aikido can analyze your GitHub Actions workflows or Jenkins files to flag issues like unpinned actions, usage of self-hosted runners with broad permissions, or secrets exposed to forked PRs. It acts like a linter for CI security. Aikido’s platform also integrates with CI pipelines to enforce policies: if someone tries to run a deployment job from an unauthorized branch or if a critical workflow file was modified in a PR, Aikido can require additional approvals. By continuously scanning the pipeline setup, Aikido helps ensure that your “software factory” is well-guarded – no open doors, no easy ways for an attacker to hijack the process. Think of it as a CI/CD configuration watchman working alongside your DevOps team.

6. Poisoned Pipeline Dependencies (Third-Party CI/CD Tools and Actions)

Modern pipelines often pull in a variety of third-party tools, Docker images, scripts, and actions to perform tasks (like code coverage, deployments, etc.). Each of these is an implicit dependency in your supply chain. If any of them is malicious or compromised, your pipeline (and the resulting software) can be compromised. A striking example of this was the attack on the reviewdog/action-setup GitHub Action and subsequent compromise of tj-actions/changed-files in 2025. Attackers managed to inject malicious code into these widely used CI actions by exploiting their update process, causing any project using them to leak secrets from CI runners. Similarly, consider pipeline scripts like the Codecov Bash uploader (which was breached in 2021) – thousands of pipelines trusted a tool that was silently exfiltrating their data. These incidents illustrate how an attacker can poison the well by targeting the tools your pipeline relies on.

How it works: Attackers look for popular CI/CD utilities or images that have supply chain weaknesses – perhaps a maintainer who doesn’t sign commits or an outdated dependency in a Docker image. By compromising the upstream project (via account takeover, exploit, or sneaking in as a contributor), they can insert malicious code. In the GitHub Actions case, an attacker gained access to the maintainers’ account or token and modified the action code, even retagging the Git refs so that what was tagged as “v1” now pointed to a malicious commit. Projects using uses: reviewdog/action-setup@v1 in their workflow suddenly pulled a tainted action that dumped secrets. Because CI systems usually fetch the latest tagged code on each run, a pipeline can be unknowingly running altered code from a third-party. Docker images used in CI (for build or test) are similarly at risk – if someone pushes a malicious update to an image like node:alpine that your pipeline uses, you’d execute whatever is in that image.

Risks: The impact here is similar to a library hijack, but potentially even more direct. CI tools often run with high privileges (some GitHub runners have sudo, etc.) and access to credentials. A poisoned action or script can immediately exfiltrate all your environment secrets, or inject backdoors into the code being built/tested. In one real incident, a malicious GitHub Action was dumping CI secrets into public logs. Another risk is that a compromised build tool could alter the compiled output (imagine a malicious compiler that always inserts a certain vulnerability or backdoor into binaries). The difficult part for defenders is these pipeline dependencies might not be as well scrutinized as your code dependencies – many teams blindly trust a Docker image or an open-source action because it’s widely used. That gives attackers a stealthy way in, and the breach might not be discovered until much later (if ever).

Mitigation: Just as you pin application dependencies, pin your pipeline dependencies. In GitHub Actions, instead of using @v1 or @main for an action, use a specific commit SHA so it can’t be silently changed. For Docker images, use digests or specific versions instead of latest. This ensures you’re running a known good version each time. Next, verify and trust but verify: prefer actions or tools that are widely trusted and ideally have a verification mechanism (some actions are GitHub-verified or have signing). Monitor upstream notifications – subscribe to security feeds of the third-party tools you use so you get alerts of any compromises. Where possible, vendor or self-host critical pipeline tools: e.g., instead of pulling a random script from the internet at build time, bake it into your codebase (after reviewing it) so it can’t change under you. Use sandboxing for risky steps – e.g., run linters or test coverage tools in isolated containers with limited access. Finally, consider adopting frameworks like Google’s SLSA (Supply Chain Levels for Software Artifacts) for your pipelines, which provide guidelines to harden build processes and require provenance for build steps.

🛡 Aikido Security Callout: Aikido’s CI/CD scanning also extends to the dependencies of your pipeline. It will check if your workflows are referencing actions with mutable tags or pulling from potentially untrusted sources. For instance, Aikido can flag that you’re using uses: someaction@latest and suggest pinning it to a commit. Aikido’s dependency scanner doesn’t just look at your app code; it can also scan your build containers and tools for known vulnerabilities or malware signatures. If you’re using a base Docker image in CI, Aikido can scan that image’s SBOM to ensure it doesn’t contain known bad components. Essentially, Aikido helps enforce that your pipeline’s ingredients are as safe as your application’s ingredients. By integrating these checks, Aikido ensures that your CI tools and actions aren’t a hidden backdoor. In case a popular tool does get compromised, Aikido’s threat intelligence would update, and you’d get an alert if your pipelines are affected – enabling you to respond quickly (e.g., pausing the pipeline, updating to a safe version) before damage is done.

7. Unpinned Versions and Mutable Dependencies (The “Latest” Problem)

Using floating or unpinned dependency versions is a supply chain vulnerability that can bite you two ways: you might unknowingly pick up a malicious update or a buggy/vulnerable update because you always pull “latest”. Whether it’s a Docker base image tagged :latest or a package version range like ^1.0.0 in npm, using non-fixed versions means your build today might fetch a different component than it did yesterday. This undermines build reproducibility and opens the door for attackers to time their moves. For example, if an attacker compromises a package and you aren’t pinning to a specific known-good version, your next build will grab the compromised version. In the GitHub Actions attack discussed earlier, one contributing factor was projects referencing a mutable tag (v1) which the attacker repointed to a malicious commit. Using strict pins (like commit SHAs or exact versions) would have prevented that tag redirection from affecting builds.

How it works: Consider a Python project that uses requests>=2.0 in its requirements (allowing any new 2.x version). When you pip install, it will fetch the newest 2.x release. If maintainers (or an attacker) release requests 2.999 tomorrow and it has issues, your environment changes unexpectedly. Or imagine your Dockerfile uses FROM node:latest; whenever the Node team updates that image (or if an attacker managed to push a lookalike image), your builds pull a new image with possibly different contents. Unpinned dependencies basically hand over control of your supply chain to external parties’ timelines. Attackers particularly like this if they gain access to push an update – they know many users will auto-upgrade. Even without a malicious actor, there’s the risk of a bad update causing failures or introducing a security hole before you realize it. The infamous left-pad incident (where a package removal broke builds globally) is an example of what can happen when many projects implicitly trust an external latest version.

Risks: The primary risk is lack of control and visibility. You may think you’re building the same code, but in reality a library or image underneath has changed. That change could be a critical vulnerability (if you auto-upgraded to a version with a new CVE) or malicious logic. In supply chain attacks, timing is key: if the adversary can briefly introduce a bad version while you’re building, they win, even if that version is later fixed. Unpinned dependencies also make incident response harder – if you don’t know exactly which version was used in a given build, it’s difficult to track if you were affected by a malicious or vulnerable release. Essentially, it erodes the reproducibility and traceability that are foundational to secure builds. The integrity of software builds depends on having deterministic inputs; “latest” is the opposite of deterministic.

Mitigation: Always pin or lock your dependencies to known good versions or digests. Use exact version numbers in package manifests, and employ lockfiles (package-lock.json, Pipfile.lock, etc.) so that everyone and every environment uses the same resolved versions. For Docker images, pin to a specific version or better yet a digest SHA (which is immutable). For Git-based dependencies or actions, pin to commit hashes. If you must allow ranges (for getting minor updates), consider using dependable bots or update tooling that alerts you to new versions rather than automatically pulling them. Implement a policy that no build should consume an artifact that isn’t explicitly tracked in source control (or in a metadata file). Additionally, maintain an SBOM for each release – this is a list of exact component versions in your product. That way if a risk emerges (say version X was compromised on date Y), you can quickly query which of your releases included that version. It’s also smart to test your dependency update process separately – don’t update in production builds blindly; have a staging or CI job that tests updates so you can catch issues. Ultimately, pinning versions gives you control: you decide when to upgrade after vetting, rather than being surprised by upstream changes.

Aikido’s tooling strongly encourages dependency pinning and version visibility. When Aikido generates an SBOM for your project, it lists every component and version – helping enforce that there are no “floating” dependencies. Aikido can also integrate with your CI to fail builds that use unpinned dependencies or mutable tags, acting as a safety net. For instance, if someone introduces FROM python:latest in a Dockerfile or adds a GitHub Action without a pinned SHA, Aikido’s scanner will flag it. Moreover, Aikido’s dependency management features can automatically open pull requests to update dependencies in a controlled manner (with security context), so you’re not stuck on old versions but can upgrade safely. By using Aikido to monitor and manage your open source components, you effectively get a shield that ensures you know exactly what you’re building. There’s power (and security) in that knowledge.

8. Outdated Components with Known Vulnerabilities

At the other end of the spectrum from “latest” issues is the risk of running outdated dependencies that have known security vulnerabilities (CVEs). This is more a traditional vulnerability, but it’s absolutely a supply chain concern: your software is only as secure as the weakest link in its dependency graph. Attackers often exploit well-known flaws in popular libraries that organizations have been slow to patch. For example, using an older version of a Struts, Log4j, or OpenSSL library with a publicized critical CVE can lead to remote code execution or data breach in your application – effectively a supply chain failure to update. With the explosion of open source, keeping everything up-to-date is challenging; however, software composition analysis (SCA) reports consistently show that a large percentage of applications have outdated libraries with known flaws. If you include a vulnerable open-source component, an attacker might not need to write a new exploit – they can just leverage the existing CVE against you.

How it manifests: Often, development teams include a library for some functionality and then forget to update it. That library might pull in others (transitive dependencies), and somewhere in that chain there could be a critical bug. For instance, consider a Node.js app pulling in a package that depends on an outdated lodash version with prototype pollution vulnerability. Your app could be exploitable via that vulnerability even if your code is fine. In CI/CD and build tools, outdated components can be lurking too – maybe your build container has an old OS package with a shellshock bug, or your CI server itself is unpatched. The manifestation is usually that a scanner or penetration test finds the known CVE, or worse, an incident occurs (e.g., the app gets hacked via that component). A notorious case was the Log4j “Log4Shell” vulnerability (CVE-2021-44228); many organizations were caught off-guard using old Log4j versions and got hit by exploits in the wild. This kind of scenario is exactly what proactive supply chain security aims to prevent.

Risks: The risk from known-vulnerable components is straightforward: attackers already know how to exploit them. Once a vulnerability is public, it often comes with proof-of-concept exploits or at least detailed descriptions. Attackers will scan the internet for applications or services that appear to be using the vulnerable component (for example, checking app headers or specific behaviors). If your software is using that component and exposed in an applicable way, you’re a target. This can lead to full system compromise, data theft, or service outages, depending on the vulnerability. Aside from direct exploitation, there’s also compliance and customer trust issues – running known vulnerabilities may violate regulations or contractual security requirements. It’s an indicator of poor security hygiene. Remember that your supply chain includes not just code you write but code you consume; neglecting updates is like leaving holes in your defenses that are well-documented in attacker playbooks.

Mitigation: Embrace a culture of continuous dependency management. This means regularly scanning your projects (and container images) for known vulnerabilities. Use SCA tools to flag when a dependency version has a CVE against it. Many package managers now have audit commands (e.g., npm audit, pip audit) to list vulnerable packages. Make this part of CI, so builds warn or fail if new vulnerabilities are introduced. Have a process (possibly automated via bots like Dependabot or Aikido’s AutoFix) to prompt upgrades to patched versions. It’s important to prioritize – not all CVEs are equal; focus on those with high severity or in software reachable from your application. Also, ensure you update your build and deployment environment – e.g., keep your base Docker images updated with security patches, update CI tools or plugins to patched releases. Another key is maintaining a bill of materials (SBOM) as mentioned, which helps you quickly answer “are we using the library that everyone is freaking out about this week?” When Log4Shell hit, organizations with a good SBOM process could immediately search and find where Log4j was in use. Finally, subscribe to security bulletins for the major projects you use, so you get heads-up when new vulnerabilities arise. Rapid patching is crucial; attackers often start exploiting popular CVEs within days or even hours of announcement.

Aikido’s dependency scanner and SCA capabilities are built to tackle this exact problem. It will scan your projects to identify all open-source components and check them against a continuously updated vulnerability database. The output isn’t just a list of issues – Aikido provides actionable info like severity, whether there’s a fix available, and even an AutoFix feature that can automatically generate secure update patches. For example, if your Maven project is using an old Struts library with a critical flaw, Aikido can suggest the safe version and update your pom.xml for you. Moreover, Aikido integrates across your development workflow (IDE plugins, PR checks, CI) so that known vulnerabilities are caught early, not after your software is in production. It also helps you generate SBOMs with ease, giving you visibility into what’s in your software. This means when the next zero-day in a common library makes headlines, you can quickly query your Aikido dashboard to see if you’re affected. Staying on top of updates becomes much easier when Aikido continuously watches your back, ensuring that outdated components don’t linger unaddressed.

9. Lack of Integrity Verification (Insufficient Signing and Origin Validation)

The final vulnerability to highlight is a more systemic one: failing to verify the integrity and origin of components. In other words, not using or checking signatures, checksums, or provenance for the code and binaries that flow through your software supply chain. Without integrity verification, you are essentially trusting by default. Attackers can exploit this by tampering with artifacts or impersonating sources. For instance, if you download a third-party library or installer over plain HTTP or from a mirror site without verifying a hash/signature, an attacker in the middle could serve you a compromised version. Similarly, if you don’t verify that a container image is signed by a trusted party, someone could trick you into running a lookalike image with a backdoor. Even within CI/CD, lack of verification means if an attacker compromises one step, subsequent steps might blindly trust outputs. An illustrative case in the Docker world was the “Ghostwriting” or image layer tampering attack, where an image’s content was altered without changing its manifest digest, thus bypassing naive validation. The principle carries to supply chain in general: without rigorous integrity checks, attackers can slip in unnoticed changes.

How it works: Code signing and verification are the primary defenses here. Many package ecosystems now support signing packages (e.g., npm’s package signatures, PyPI’s upcoming signing, etc.), and container registries support image signing (like Docker Content Trust with Notary, or Sigstore Cosign for Kubernetes). If these are not used, or not enforced, an attacker who can either intercept network traffic or breach a build pipeline could insert malicious artifacts that will be accepted as genuine. Lack of integrity verification also includes not verifying dependency integrity: e.g., not checking a downloaded library’s checksum against what the vendor published. In CI, not verifying the identity of the source (like not checking that a Git commit is signed or came from the expected repository) can lead to pulling in wrong code. The scenario is often an advanced attack – e.g., a sophisticated adversary might compromise a DNS or BGP route to your artifact server and serve you malware for a short period, or compromise a build server to alter binaries post-compilation. If you’re not verifying signatures/hashes, you’d be none the wiser.

Risks: The obvious risk is a complete compromise of software integrity. You might ship software that has been tampered with by attackers, undermining all other security measures. It’s especially concerning for things like installer files, updates, or container images that get distributed widely – an attack here can have a massive blast radius (akin to the SolarWinds incident where a build system compromise led to a trojaned software update). Another risk is supply chain attestation – if you can’t prove the integrity of your components, it’s hard to trust them in secure environments. We’re seeing more industry and regulatory push for verified provenance (e.g., US Executive Order on secure software requires checking integrity via SBOM and signatures). Lack of verification can also allow simpler attacks like dependency substitution (an attacker swaps out a file or library on your build machine because you never verify it). Essentially, not verifying is an invitation for attackers to get creative, because you’ll only catch them if something blatantly breaks – stealthy modifications go unnoticed.

Mitigation: Start adopting signing and verification practices in your development lifecycle. Enable GPG or Sigstore signing for the packages and containers you build and distribute, and similarly verify signatures on the things you consume. For example, before using a binary from a release, verify its GPG signature or at least compare its SHA-256 hash with the official one. In container deployments, use tools like Cosign to verify container images against expected public keys or utilize admission controllers to block unsigned images. Implement zero-trust for artifacts: just because a file is on your network doesn’t mean it’s safe – verify it. Use HTTPS for all package and artifact downloads (most do by default now, but ensure no one’s downgrading it). For internal build processes, consider techniques like reproducible builds and storing hashes of build outputs to detect tampering. Employing an admission control in CI or deploy that says “only allow artifacts that match known good checksums or signatures” can be a last line of defense if something sneaky happened upstream. The key is to make verification automated and mandatory, so developers aren’t manually clicking “okay” on warnings but rather the pipeline refuses unverified code.

Aikido helps enforce integrity in multiple ways. Through its SBOM analysis and integration with signing tools, Aikido can validate that your dependencies and containers are what they claim to be. For instance, Aikido can integrate with Sigstore/cosign to ensure that any container image deployed via your pipeline has a valid signature from your organization – if not, it flags or blocks it. Aikido’s platform also tracks checksums of scanned components; if an artifact’s content changes unexpectedly (doesn’t match the SBOM or prior scan), that’s a red alert. Additionally, Aikido’s vulnerability database and policies include checks for things like “is this package from an official source?” which indirectly covers integrity (if someone slips in a fake package source, Aikido would detect it via metadata mismatches). By incorporating Aikido, teams get an automated integrity gatekeeper. It ensures that from code commit to build to artifact deployment, each piece can be traced and trusted. When combined with the other practices (scanning, secrets management, etc.), this gives developers confidence that their software supply chain is secure end-to-end, with Aikido verifying each link in the chain.

Conclusion: Secure Your Supply Chain from Day One

Software supply chain attacks may sound complex, but as we’ve seen, they often exploit rather basic gaps: unvetted dependencies, unsecured pipelines, leaked credentials, and unverified artifacts. The good news is that by being aware of these common vulnerability types, dedavelopment teams can take proactive steps to close the holes. Security isn’t someone else’s job down the line – it starts at day one of development and continues through every commit, build, and deployment. Adopting a developer-friendly security approach means baking in practices like dependency scanning, secrets detection, and CI/CD auditing into your daily workflow, rather than treating them as afterthoughts.

The threats are real and growing – from malicious npm packages to CI pipeline breaches – but with the right mindset and tools, you can stay ahead. Encourage your team to practice good “supply chain hygiene”: review what you import, rotate and protect secrets, lock down your build process, and verify everything. Automate as much as possible using modern DevSecOps tools. In fact, leveraging platforms like Aikido Security can make this far easier. Aikido acts as your intelligent security assistant, catching risky dependencies and configurations early, and guiding you with fixes (often automated) before they become incidents.

Don’t wait for a headline-grabbing attack to force action. Take charge of your software supply chain security now. Start by integrating security tooling into your CI/CD pipeline and IDE – for example, try Aikido’s free developer toolkit to scan your dependencies and pipelines for vulnerabilities and secrets. Educate your developers about these threats so they become stakeholders in protection, not just consumers of open source. With vigilance and the aid of smart security automation, you can deliver software with confidence that your supply chain – from code to cloud – is resilient against attackers. Secure coding and building isn’t a hurdle to velocity, it’s an investment in your product’s trust and reliability. Empower your team to adopt these practices today, and you’ll significantly reduce the risk of becoming the next supply chain cautionary tale. Happy (and secure) coding!

Continue reading:

Top 9 Docker Container Security Vulnerabilities

Top 7 Cloud Security Vulnerabilities

Top 10 Web Application Security Vulnerabilities Every Team Should Know

Top 9 Kubernetes Security Vulnerabilities and Misconfigurations

Top Code Security Vulnerabilities Found in Modern Applications

Top 10 Python Security Vulnerabilities Developers Should Avoid

Top JavaScript Security Vulnerabilities in Modern Web Apps

Secure your software now

.avif)