Top Python Security Vulnerabilities

In today’s fast-paced development pipelines, insecure Python code can introduce serious risks. Python is loved for its simplicity, but that same flexibility can turn dangerous if secure coding practices are neglected. From code injection pitfalls to vulnerable third-party libraries, even a small oversight can open the door for attackers. Recent studies show millions of credentials and API keys accidentally leaked in code – a stark reminder that security can’t be an afterthought. In this article, we’ll break down some of the top Python language-level security vulnerabilities (beyond just web framework issues), illustrate their impact with real examples (including CVEs in popular libraries), and offer tips to mitigate each risk. We’ll also highlight how integrating security tools (like Aikido’s SAST, secret scanning, and dependency checks) early in your workflow can help catch these issues before they wreak havoc.

The Top 10 Python Security Vulnerabilities

Below are ten of the most common and dangerous security vulnerabilities in Python applications. For each, we explain how the vulnerability arises, the potential impact, and how to fix or prevent it – with a special callout to how modern security tooling can help.

1. Arbitrary Code Execution via eval() and exec()

Python’s eval() (and its cousin exec()) allows dynamic execution of Python code from strings. Used injudiciously, eval can turn a simple script into a ticking time bomb. If an attacker can influence the string passed to eval(), they can execute any code they want – from printing data to deleting files or worse. As one developer put it, “The problem with eval is that it risks allowing attackers to craft malicious input ... that tricks your program into executing harmful code”. In other words, an eval(user_input) call might work today with safe inputs, but a cleverly crafted input tomorrow (like __import__('os').system('rm -rf /')) could wipe your server.

Impact: Arbitrary code execution is as severe as it sounds – it means a complete compromise of the application. Attackers could steal data, modify it, or take over the host. This isn’t a theoretical edge case: real breaches have occurred from unsafe use of eval. Even if your use of eval is “safe” today (e.g. only evaluating mathematical expressions), it creates a latent vulnerability that future changes can accidentally trigger.

Mitigation: Never use eval or exec on untrusted input. In fact, avoid them altogether unless absolutely necessary. Python provides safer alternatives for most use cases (for example, use literal evaluation via ast.literal_eval for reading data structures, or dispatch tables for calling functions instead of building a string to eval). Always validate or sanitize inputs rigorously if dynamic execution is needed.

Aikido Security Callout: A good static analysis tool (SAST) can catch use of dangerous functions. Aikido’s code scanning, for instance, can flag instances of eval() or exec() in your code. This helps you identify risky code paths during code review or CI – before they ever reach production. By integrating such scanning in your pipeline, you’ll get alerted whenever a new use of eval sneaks in, so it can be refactored or scrutinized immediately.

2. OS Command Injection via subprocess or os.system

Building on the code injection theme, another critical pitfall is OS command injection. This happens when a Python program passes user input to system shell commands without proper sanitization. Functions like os.system(), subprocess.run() (with shell=True), or even uses of backticks/popen can execute shell commands. If user-controlled data is concatenated into those commands, an attacker can inject rogue commands. For example:

# Vulnerable snippet:filename = input("Enter the filename to delete: ")os.system(f"rm -f {filename}")

An attacker could input file.txt; shutdown -h now and suddenly our innocent script executes rm -f file.txt; shutdown -h now. In a real incident, attackers exploited an MLflow vulnerability that stemmed from passing unsanitized data to an os.system call inside a predict function. As Snyk’s security researchers note, command injection allows unauthorized command execution, leading to data breaches, system compromise, and other malicious activities.

Impact: OS command injection can be devastating. Attackers may chain commands to steal sensitive files (e.g. read application config or credentials), create backdoor user accounts, or pivot deeper into the network. Since these commands run with the same privileges as your Python process, the impact could range from dumping a database to full server takeover. Breaches enabled by command injections often result in severe financial and reputational damage.

Mitigation: Never directly concatenate user input into shell commands. If you need to call external programs, use the safer APIs: Python’s subprocess module allows you to pass arguments as a list (which avoids invoking an actual shell). For instance, use subprocess.run(["rm", "-f", filename]) instead of os.system("rm -f " + filename). If using subprocess with shell=True is unavoidable, ensure input is strictly validated or sanitized (for example, allow only expected alphanumeric filenames). Additionally, consider using high-level libraries for OS tasks (e.g., use Python’s file handling instead of rm for deleting a file).

Aikido Security Callout: Aikido’s static code analysis includes rules to detect command injection patterns. It will warn you if it sees something like os.system(user_input) or subprocess.Popen(..., shell=True) with variable input. In practice, this means your CI pipeline can fail a build if a dangerous usage is introduced. By catching these during development, you prevent that “oops” moment where a forgotten debug snippet or a quick-and-dirty shell call becomes an open door for attackers.

3. Hardcoded Secrets in Code

Hardcoding secrets – like API keys, credentials, tokens, or private keys – in source code is a pervasive and dangerous practice. It’s easy to do (“just put the AWS key here for now…”), but hard to undo, since secrets can linger in commit history even after removal. Exposed secrets are a goldmine for attackers. In fact, secret leaks have exploded recently: in 2022, one analysis of public GitHub repos found 10 million secrets exposed in just 1 year (a 67% increase over the previous year). These aren’t just committed by junior developers – it happens across all levels. Once leaked, secrets have been used in major breaches (for example, an attacker used hardcoded admin creds in code to breach Uber’s internal systems).

Impact: If an attacker finds a secret (in a public repo, a leaked backup, a Docker image, etc.), they can often pivot directly into your systems. Imagine a hardcoded database password – if leaked, an attacker could log into your database and extract user data. Hardcoded cloud API keys are even worse: cloud providers report that exposed credentials are typically exploited within minutes of discovery by bots scanning repos. The blast radius can include full cloud environment compromise, hefty cloud bills for cryptominers, or unauthorized access to sensitive services. Secrets truly are “the keys to the kingdom,” so leaking them is like leaving your front door unlocked for burglars.

Mitigation: Never commit real secrets to code. Use configuration files, environment variables, or secret management services (like HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, etc.) to inject secrets at runtime instead. If you must include a default or example credential in code, ensure it’s a non-production placeholder. Conduct regular secret scanning on your codebase and history; if a secret does slip in, rotate it immediately (i.e., invalidate and replace it) and purge the commit if possible. Employ the principle of least privilege – even if a secret leaks, a read-only token is less damaging than a full admin key.

Aikido Security Callout: This is where secret detection tools shine. Aikido’s secret scanning (inspired by the likes of GitGuardian and others) will automatically search for patterns like API keys, credentials, certificates, and more in your repositories. It can alert you the moment a developer accidentally commits a secret. Integrating such a tool into your CI/CD (or even pre-commit hooks) means that a hardcoded AWS key gets flagged before it ever reaches GitHub. Aikido’s platform even offers automated remediation – for example, revoking the exposed credential and guiding the developer to use a secure storage method instead.

4. Insecure Deserialization (Pickle Abuse)

Python’s pickle module provides a way to serialize and deserialize complex objects. However, pickle is notoriously insecure by design. Unpickling data from an untrusted source can execute arbitrary code during the deserialization process. The Python documentation itself is crystal clear on this: “The pickle module is not intended to be secure against malicious data. Never unpickle data received from an untrusted or unauthenticated source.” In practice, this means if an attacker can feed your application a pickle (e.g., a forged cookie or a cached object), they could run any Python code on your server – essentially a pre-auth RCE (Remote Code Execution) vulnerability.

Real-world example: A developer might use pickle.loads() on data received over a network (perhaps thinking it’s just a convenient way to transmit Python objects). Attackers can craft a pickle payload that, when unpickled, executes system commands. Security researchers have demonstrated trivial exploits where unpickling a seemingly innocuous object triggers a reverse shell to the attacker. In one case, a 15-line exploit using pickle was enough to spawn a shell, because the application blindly trusted pickle data over the network.

Impact: Insecure deserialization is a critical issue – typically leading to full remote code execution. Because pickle can invoke any class and method during loading, an attacker can abuse it to do things like delete files, install malware, or pivot to other internal services. Unlike some vulnerabilities that “just” leak data, this gives direct control to the attacker. The impact is limited only by what the running application’s permissions are (and often Python apps run with plenty of privileges).

Mitigation: Do not use pickle (or similar serialization like marshal) on data from untrusted sources. If you need to exchange data between systems, use safe formats like JSON or XML – and even then, be cautious (validate the inputs). For Python-specific use cases (sharing objects), consider jsonpickle in safe mode or other safer serializers, but always assume input may be hostile. If you absolutely must accept pickled data (e.g., for compatibility), treat it as code: require authentication, use digital signatures to ensure it’s from a trusted source, or run the deserialization in a sandbox with restricted privileges. The simplest advice is usually the best: avoid dynamic deserialization of user input altogether.

Aikido Security Callout: Modern code scanners can detect usage of dangerous APIs like pickle.loads or pickle.load on potentially external data. Aikido’s SAST engine, for instance, has checks for insecure deserialization – it knows that any invocation of pickle is a red flag unless proven otherwise. It will highlight these during code reviews. Moreover, Aikido’s dependency scanner keeps track of known deserialization CVEs. For example, some libraries (or frameworks) have had deserialization flaws (not just pickle – even things like XML or YAML, which we’ll cover next). Aikido will alert you if you’re using a vulnerable version of such a library and suggest upgrades or patches.

5. Unsafe YAML Loading (PyYAML Vulnerability)

Serialization issues aren’t limited to pickle. YAML, a human-friendly data format, can also bite you if used unsafely. The popular PyYAML library had a well-known flaw: using yaml.load() on untrusted input could execute arbitrary Python objects. In fact, PyYAML’s load() was basically as powerful as pickle. CVE-2017-18342 was assigned to this issue – "In PyYAML before 5.1, the yaml.load() API could execute arbitrary code if used with untrusted data." The fix was to introduce a safe_load function and make load() default to safe mode in newer versions. But many applications still may inadvertently use the old yaml.load (or an older PyYAML version), thinking they are just parsing a config, when in reality an attacker could craft a YAML that runs code.

Impact: Similar to pickle, the impact is remote code execution. For example, a YAML file can embed a Python object of a type that, upon construction, runs a system call. Attackers exploiting this can cause your app to execute OS commands the moment it tries to parse a malicious YAML. This can be exploited through any functionality that parses user-provided YAML (common scenarios include configuration importers, Kubernetes templating in CI/CD, or web apps that accept YAML input). The CVE above was marked Critical (CVSS 9.8) precisely because of how easily it could be triggered and how severe the outcome is.

Mitigation: Always use safe loading methods for data formats. In PyYAML, use yaml.safe_load() for any content that is not fully trusted. This mode only parses basic YAML types (strings, ints, lists, dicts) and will refuse to instantiate custom objects. If you are on PyYAML < 5.1, upgrade the library – the old load() is outright unsafe. Similarly, be wary of other serialization formats: use json.loads (JSON has no code execution by design, which is good), or if using pickle-like alternatives, ensure they have a safe mode. A defense-in-depth idea: run parsing in a low-privilege environment or sandbox if possible (so even if code executes, it can’t do much harm).

Aikido Security Callout: Dependency scanning is key here. Aikido’s dependency analyzer would flag that you have PyYAML <5.1 in your requirements, warning you of CVE-2017-18342 and advising an upgrade. On the code side, Aikido’s SAST can also catch usage of yaml.load(...) and suggest using safe_load instead. It’s all about catching the issue at two levels: make sure you’re using a safe library version, and ensure you’re calling the safe functions. By integrating these checks, you’d be notified during development that “hey, this YAML parsing call is unsafe” with guidance to fix it.

6. Directory Traversal via Insecure File Operations (Tarfile Extraction)

Handling files is common in Python (e.g., unpacking user-uploaded archives). But naive file operations can introduce path traversal vulnerabilities. A prominent example is Python’s built-in tarfile module. It was revealed that for over 15 years, tarfile.extractall() was vulnerable to a path traversal attack (dubbed a “15-year-old vulnerability” when rediscovered). If a malicious tar archive contains file entries with ../ in their names, extractall would happily write files outside the intended directory, potentially overwriting critical system files. This is tracked as CVE-2007-4559. Although it’s an old CVE, it remains unfixed in the Python standard library as of this writing, and research in 2022 showed hundreds of thousands of repositories are still using tarfile in a vulnerable way.

An attacker could upload or supply a specially crafted tarfile such that, when your code extracts it, it plants a payload (e.g., a web shell, or an overwritten config) into a location that the attacker should not have access to. In one demo, researchers exploited this to get code execution by overwriting a Python package’s own code after extraction.

It’s not just tar files – similar issues can occur with zip files (zip slip vulnerability) or any file operation where you construct paths from external input. Without proper checks, an archive entry named ../../../../../etc/passwd will write to /etc/passwd on extraction.

Impact: Path traversal can lead to arbitrary file write (or read, in some cases) on the server. Writing files in the wrong place can escalate to code execution – for instance, overwriting an app’s config to point to attacker-controlled code, or dropping a Trojan binary in the PATH. Even if it doesn’t immediately lead to RCE, overwriting critical files can sabotage system integrity or facilitate later attacks. Consider the consequences of an attacker overwriting your application’s .env file or a script that gets executed – they could insert malicious commands. In the case of CVE-2007-4559, the community upgraded its severity when it was shown code execution is often a direct consequence of exploiting the file overwrite.

Mitigation: Never extract archives from untrusted sources without validation. For tarfile, use tarfile.extractall(path, members=...) and manually filter the members. You can implement a check to ensure no member’s filepath is outside the target directory (e.g., by resolving absolute paths and checking for traversal patterns). The Python documentation now includes a code snippet to do this safely – essentially rejecting any file with .. or drive prefixes. Alternatively, consider using third-party libraries that perform safe extraction. For zip files, similarly inspect names before writing, or use libraries that mitigate zip slip. Always least-privilege: if possible, run extraction in a sandbox or a directory with limited permissions. That way, even if an exploit tries to break out, it can’t hit system-critical files.

Aikido Security Callout: Aikido’s static analysis can detect dangerous patterns like tarfile.extractall() usage without safe member filtering. It knows about CVE-2007-4559 and can flag instances in your code where you call extractall or extract without precautions. This serves as a prompt to implement the proper checks. Additionally, Aikido’s vulnerability intelligence feed (its in-house research) keeps track of these “lurking” issues in both standard libraries and popular packages. By scanning your code and dependencies, it will surface a warning like “Potential path traversal in tarfile usage – consider validating archive contents,” linking to best practice guidance. In short, it helps developers catch a 15-year-old bug that might otherwise go unnoticed in their code.

7. Using Outdated Libraries with Known Vulnerabilities (Requests, urllib3, etc.)

Python’s rich ecosystem of packages is one of its strengths – but every dependency you include can also introduce vulnerabilities if not kept up-to-date. High-profile Python libraries have had their share of CVEs. For example, the widely used Requests HTTP library has had bugs like:

- CVE-2023-32681 – where Requests would leak HTTP Proxy credentials in certain redirect scenarios, sending

Proxy-Authorizationheaders to destination servers and potentially exposing sensitive info. (This was fixed in Requests 2.31.0.) - CVE-2024-35195 – a logic flaw where if you disabled SSL cert verification once in a Session, Requests would persistently ignore verification for subsequent requests to the same host, even if you tried to re-enable it. Essentially, once broken, always broken – a nasty surprise that could silently leave connections insecure. Fixed in 2.32.0.

- CRLF Injection in urllib3 – urllib3 (used by Requests under the hood) had a vulnerability allowing CRLF injection in HTTP headers if an attacker controlled part of the request URL or method (e.g., newline characters in a header could be inserted). This could be abused to smuggle headers or split responses, potentially leading to session hijacking or manipulating web caches. (Multiple CVEs, e.g., CVE-2019-9740 for Python’s builtin urllib, were assigned to such issues.)

These are just a few examples. Other notable ones include vulnerabilities in URL parsing (e.g., CVE-2023-24329, an issue in urllib.parse that allowed attackers to bypass URL blocklists by using a tricky URL starting with a space or control char), and issues in package management tools (like pip’s past vulnerability CVE-2018-20225 which allowed a malicious download to overwrite arbitrary files). Even popular data libraries (Pandas, NumPy) occasionally have security fixes (often DoS or memory corruption issues).

Impact: Known vulnerabilities in libraries can have a wide range of impacts – from information leakage and denial of service up to full compromise – depending on the bug. The key point is that attackers actively scan for applications using outdated versions. If you’re running an old Requests and your app makes network calls, an attacker might exploit the proxy auth leak to steal credentials. Or if you have an outdated urllib3, they might exploit CRLF injection to poison your HTTP interactions. Since these vulnerabilities are public, attackers know exactly what to look for. Failing to update dependencies is like leaving known holes unpatched in your app.

Mitigation: Stay on top of dependency updates and security advisories. Use tools to check for known CVEs in your dependencies (pip-tools, GitHub’s Dependabot, or commercial SCA tools). When a new critical CVE is announced (e.g., a severe bug in Django, Flask, Requests, etc.), prioritize upgrading to a fixed version. Where possible, pin your dependencies to known-good versions and review changelogs of updates. Also consider minimal version pins: e.g., require requests>=2.31.0 if you know older ones are vulnerable. Additionally, employ defense-in-depth: for instance, even if Requests had a cert verification bug, you could add a layer of network security (like TLS interception or additional certificate pinning) to mitigate the risk. But the simplest is: keep your packages updated.

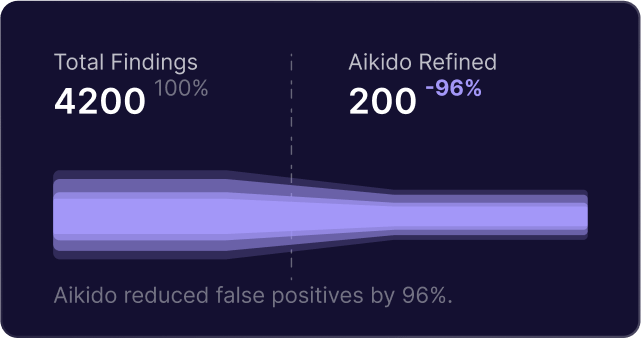

Aikido Security Callout: This is where Software Composition Analysis (SCA) in Aikido comes into play. Aikido’s dependency scanner continuously checks your project’s requirements (and even your transitive dependencies) against a database of known vulnerabilities. It will alert you, “Library X version Y is vulnerable to CVE-2023-32681”, often providing details and a recommended fixed version. Even better, Aikido’s platform can do automated fixes – for example, opening a pull request to bump a version. By integrating this into your CI/CD, you ensure that you’re not deploying containers or applications with outdated libraries. In short, tools like Aikido help you catch known CVEs and even automatically remediate them, complementing open-source scanners with custom rules and up-to-date intel.

8. Disabling Security Features (e.g., Ignoring SSL Certificate Validation)

Sometimes in development or testing, engineers turn off important security checks – and then the code ships to production that way. A classic example in Python is making HTTP requests with SSL verification disabled. The Requests library (and others like urllib3) allow a verify=False flag to ignore SSL certificate errors. This is convenient when dealing with self-signed certs in a dev environment, but if it makes it to prod, it exposes you to man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks. The Requests documentation explicitly warns: when verify=False, the client will accept any certificate – ignoring host name mismatches or expired/self-signed certs – making your application vulnerable to MITM attacks. Essentially, you no longer confirm you’re talking to the real server. An attacker could intercept your traffic (especially if they can spoof DNS or are on the same network) and present any certificate to hijack the connection.

Beyond SSL verification, other disabled features can haunt you too: for instance, using HTTP instead of HTTPS for sensitive communication, turning off TLS host name checking manually, or disabling Python’s built-in safety nets (like running the interpreter with assertions off if those assertions were guarding a security-critical check).

Impact: If an attacker can get in the middle of your traffic (which is easier than many think, especially in cloud or container networks, or public Wi-Fi, etc.), they can decrypt and modify data in transit when cert verification is off. This could mean an attacker steals API tokens, injects malicious responses, or impersonates services. In a microservice architecture, one compromised service or network foothold could allow pivoting by intercepting calls from one service to another if those calls aren’t properly verified. We’ve also seen scenarios where turning off SSL verification in an API client library allowed attackers to serve malware from what should have been a trusted update server, simply by using a self-signed cert on a spoofed domain. The fallout can be stolen data, account takeover, or injection of malicious data/commands into your app’s functioning.

Mitigation: Never disable SSL verification in production code. If you truly must (e.g., connecting to an internal service with a self-signed cert), then at least pin the certificate or thumbprint so you’re not blindly trusting any cert. Better yet, use a private CA and make your internal certs trusted by providing the CA bundle. During development, if you use verify=False, be extremely cautious to remove it before committing or use configuration to only disable it in non-prod environments. Code reviews should treat verify=False as a big red flag. Additionally, consider using tools like linters to forbid this flag in committed code. The same goes for other shortcuts – e.g., don’t catch and ignore security exceptions, don’t disable authentication or CSRF in debug and forget to re-enable, etc.

Aikido Security Callout: Aikido’s scanners can detect usage of risky settings like verify=False in requests. In fact, it can enforce policies (similar to how Prisma/Checkov policies work) to ensure no code is disabling certificate checks. If such a pattern is found, Aikido will call it out in the scan results, treating it as a vulnerability. It might say “SSL certificate verification disabled here – this should not be used in production” with a link to the line of code. By integrating that in CI, you effectively prevent the “I left a debug flag on” scenario. Moreover, the earlier-mentioned dependency scanning will also clue you in on bugs like CVE-2024-35195, where even unintentional disabling persists – highlighting that you need to update your library to fully restore security.

9. Malicious or Compromised Packages (Software Supply Chain Attacks)

Not all threats come from mistakes in your own code – sometimes the code you pulled from PyPI itself is the attack. Supply chain attacks via malicious Python packages have surged in recent years. Attackers publish typo-squatted or outright fake packages to PyPI, naming them similar to popular libraries (e.g., reqeusts instead of requests) or appealing names like free-net-vpn. Unsuspecting developers install them, and the malicious code runs during install (in setup.py) or upon import. For example, in 2022, ten malicious PyPI packages were discovered that impersonated common libraries and injected info-stealing malware into developers’ systems. One package, mimicking a well-known one, was designed to search for AWS credentials and send them to an attacker via a Discord webhook. Another called WINRPCexploit claimed to be an exploit tool but actually exfiltrated all environment variables (often containing secrets) to the attacker.

Even legitimate packages can become compromised if an attacker gains access to the maintainer’s account (as happened with event-stream in Node.js, and has happened in Python too). There have been cases where widely used packages were briefly hijacked to include malicious code in new releases. For instance, a package might suddenly start sending usage telemetry (spying) or include a backdoor triggered under certain conditions.

Impact: The impact of malicious packages can be severe and far-reaching. Since these packages often execute code at install time (via setup scripts) or when imported, they can do anything your user can do: steal credentials (from config files, env vars, AWS CLI config, etc.), install trojans, encrypt files (ransomware), or open reverse shells. And because they often run with the developer’s privileges, it can compromise not just the app but the entire system or credentials that developer has. In a CI pipeline, a poisoned package could exfiltrate secrets from your CI environment. In a production environment, a malicious dependency could become a backdoor for attackers to continuously exploit. Supply chain attacks are particularly insidious because they undermine trust in the very tools we use.

Mitigation: Carefully vet and monitor your dependencies. Some best practices: Pin dependencies to specific versions (so you don’t automatically pull a tampered update). Verify checksums or signatures of packages (PyPI now supports GPG signing and similar, though not all packages use it). Use tools like pip install --no-build-isolation --only-binary=:all: for known-good wheels to avoid executing setup.py of unknown packages. Consider employing a local PyPI proxy or mirror and only allow vetted packages through. Always read the package details: if requests has 100 million downloads and suddenly there’s a new reqeusts package – that’s suspicious. The PyPI security features (like 2FA for maintainers) are improving, but the onus is on users too: don’t install random packages without scrutiny. If possible, review the source of new dependencies (at least a quick scan for obvious malicious patterns like os.system('curl ...')).

Aikido Security Callout: Aikido’s platform tackles supply chain risks in multiple ways. First, its dependency scanning will flag packages that are known malware or have suspicious behavior. Aikido continuously ingests threat intelligence (malicious package indicators) and can warn you, “Package X is reported as malicious – do not use it.” Secondly, Aikido SafeChain (an open-source tool by Aikido) can prevent installation of untrusted packages. It essentially blocks packages that haven’t aged enough or that appear suddenly in your dependency tree, mitigating typosquatting attacks by requiring a “cool-off” period (e.g., only install packages that have existed for >24 hours, to avoid freshly published malware). By integrating these defenses, you add an automated watchdog whenever you do pip install. In effect, Aikido helps ensure that the libraries you depend on aren’t betraying you – catching known bad actors and enforcing policies to make it harder for new ones to slip in.

10. Weak Cryptography Practices (Insufficient Randomness & Poor Crypto Use)

Cryptography is hard, and using it incorrectly can undermine security just as much as an outright bug. In Python, a common mistake is using the wrong random number generator for security-sensitive contexts. For example, developers might use random.random() or random.randrange() to generate a password reset token or session ID. However, the standard random module is not cryptographically secure – it uses predictable algorithms not suited for secret generation. Python introduced the secrets module for this reason, stating that secrets should be used for security-critical randomness in preference to the default pseudo-random number generator in the random module, which is designed for modeling and simulation, not security or cryptography. If you use random for tokens, an attacker might be able to predict values (given enough observations or knowledge of the seed).

Another weak practice is using outdated or weak algorithms. For instance, using MD5 or SHA1 for password hashing (both are considered broken for this purpose) or not salting passwords at all. Or rolling your own “encryption” (e.g., a homebrew XOR scheme) instead of using proven libraries. These weaknesses might not manifest as a CVE in your code, but they significantly lower the bar for attackers. A real example: if passwords are stored unsalted with SHA-1, an attacker who steals the hash database can crack most passwords quickly using precomputed rainbow tables.

Impact: Insecure randomness could lead to account hijacking or token forgery. Imagine an attacker guesses session cookies because they were derived from predictable PRNG output – this is not just theory, it has happened in poorly designed systems. Weak hashing or encryption means that if an attacker breaches one layer (say, gets read access to a database or intercepts encrypted traffic), they can easily decrypt or crack the supposedly protected data. Overall, weak crypto gives a false sense of security; attackers might not need an “exploit” when they can simply brute-force or predict what they need.

Mitigation: Follow current cryptographic best practices. Use the secrets module or os.urandom() for generating any secret tokens, keys, or nonces. Use high-level libraries for encryption (like Fernet in the cryptography library) rather than writing your own crypto. For password storage, use established KDFs (bcrypt, Argon2, PBKDF2 with adequate iterations) – never plain hashes without salt. Keep algorithms updated; for instance, SHA-256 is good for integrity but for passwords you’d still want a slow hash like bcrypt. And always enable TLS for network communication, using modern protocols (TLS 1.2+). Essentially, defer to well-vetted implementations instead of custom or legacy approaches. Also, stay aware of deprecations: if an SSL/TLS setting or cipher is no longer recommended (Python’s ssl module usually updates defaults, but be mindful if you override settings).

Aikido Security Callout: Aikido’s SAST can help spot some crypto no-nos – for example, it can warn if it sees the random module being used where secrets would be appropriate, or if it finds MD5 being used in a security context. Moreover, Aikido’s vulnerability intelligence will alert you if you’re using a known weak algorithm in a context that had prior CVEs (for instance, if a library you use defaults to an insecure mode, Aikido might point that out). While human oversight is crucial in cryptography, having an automated tool to double-check doesn’t hurt. It’s like a linter for security: if you inadvertently commit token = random.random(), a tool can say “Are you sure? This isn’t cryptographically secure.” This kind of feedback early on can nudge developers towards the right modules (perhaps even suggesting: import secrets and secrets.token_hex() as an alternative). In sum, Aikido aids in enforcing cryptographic hygiene by catching obvious weak patterns and keeping you informed about cryptography-related vulnerabilities in the ecosystem.

Conclusion: Secure Your Python Code from the Start

Python’s flexibility and rich ecosystem can be a double-edged sword – powerful in the hands of developers, but offering many avenues for attackers if proper care isn’t taken. We’ve explored how things like dynamic code execution, injection vulnerabilities, leaked secrets, outdated dependencies, and other pitfalls can undermine the security of your Python applications. The good news is that each of these flaws is preventable with a mix of best practices and the right tooling:

- Adopt secure coding practices: validate inputs, avoid dangerous functions, and use safe defaults (e.g. safe loaders, secure random, updated algorithms).

- Keep your dependencies updated and vetted: don’t let known CVEs linger in your requirements, and be cautious of what you install.

- Integrate security into your development pipeline: this means running static analysis, secret scanning, and dependency audits as you code and during CI, not after an incident.

Modern DevSecOps platforms like Aikido can make this process much easier by automating the detection of these issues – from catching a hardcoded password before it leaves your laptop, to blocking a vulnerable package from being deployed, to alerting you of a newly disclosed flaw in one of your libs. As the Red Hat container security report noted, nearly half of teams lose sleep over container (and by extension, software) security – the same likely holds true for Python application security. By shifting security left – i.e., addressing it early in development – you can significantly reduce the chances of a late-night emergency caused by an avoidable Python bug.

In summary, staying informed and proactive is key. Keep learning about secure coding (the Python Security Guide and OWASP resources are great), encourage code reviews with security in mind, and leverage automated tools as your safety net. Python developers who build security in from the start will save their organizations time, money, and reputation in the long run. Let’s write code that’s not just clever and clean, but also safe and secure. Your future self (and your users) will thank you for it.

Continue reading:

Top 9 Docker Container Security Vulnerabilities

Top 7 Cloud Security Vulnerabilities

Top 10 Web Application Security Vulnerabilities Every Team Should Know

Top 9 Kubernetes Security Vulnerabilities and Misconfigurations

Top Code Security Vulnerabilities Found in Modern Applications Top JavaScript Security Vulnerabilities in Modern Web Apps

Top 9 Software Supply Chain Security Vulnerabilities Explained

Secure your software now

.avif)