Typosquatting, registering a typoed version of a popular package and waiting for a developer to accidentally type and install the wrong package, has been around for a decade in npm. It’s nothing new— the registry has protections for it.

Then AI came along and changed everything again. Slopsquatting is the new, AI flavor of typosquatting. Instead of betting on human typos, attackers bet on AI hallucinations, the package names that LLMs confidently recommend that don't actually exist. For a while, this was treated as a theoretical risk, but that's no longer the case. AI hallucinations are in the room with us, and so are the slopsquatters.

In this piece, we'll look at how slopsquatting works, what researchers are finding in the wild right now, and what you can actually do about it.

What is slopsquatting?

Slopsquatting, also called hallucination squatting, is what happens when an attacker registers a package name that AI models tend to hallucinate, then waits for developers to install it on an AI's recommendation. Squatting attackers rely on AI assistants confidently suggesting package names that don't exist, and developers trusting them that it's a real package that they have asked for.

When a developer run install on this package name, they get the attacker's package. The package will generally run some post-install script that steal whatever credentials are sitting in the environment (API keys, cloud tokens, npm auth tokens) and forwards them to the attacker.

While some packages just include the attack in a post-install script, fancier packages skip putting malicious code in the package entirely, instead using npm's support for URL-based dependencies to fetch a payload from an external server at install time. The package looks clean to any naive static scanner because there’s no obviously malicious code.

Let’s say you ask your AI to install a JavaScript linter package. It offers unused-imports and asks if you want to install it (if it doesn’t just bypass asking you altogether). This sounds like the package you’ve used before, so you install it.

Claude wants to run: npm install unused-imports

[y] Accept [n] Reject [e] Edit [Esc] CancelHowever, the real package is eslint-plugin-unused-imports. Turns out, unused-imports is a malicious package, and surprise! You just installed malware! (This is actually a real malicious package, by the way, and potentially an intentional slopsquatting attack. You can look it up on Aikido Intel. npm has it under a security hold now).

LLMs actually hallucinate package names quite a bit. Mackenzie Jackson, Developer Advocate at Aikido Security, described a hallucination he encountered on an episode of the Secure Disclosure podcast. He asked an AI to help connect his Node.js project to an OrientDB database, a technically feasible but uncommon combination with no obvious package solution. Instead of admitting it was stumped, the model invented package names. Mackenzie says of the AI’s thought process, "I don't have anything for you, but I need to have something for you, so here's what I think packages for this would be called."

How is slopsquatting different from typosquatting?

Typosquatting is when an attacker registers a malicious package with a name close enough to a popular package that a user will typo their way into it. Attackers will find a high-download package with a name that's easy to misspell, drop a hyphen, swap two letters, add an extra character, and “squat” on the misspelled package before anyone else does. Typosquatting has been a fixture of npm since at least 2017, when an attacker published crossenv, a squat of the popular cross-env package. npm now has protections against this, by preventing the registration of package names too similar to exisiting ones.

Slopsquatting is typosquatting, but instead of betting on a human's fat fingers, attackers are betting on an AI being confidently wrong. (Yeah, that’s how reliable AI is considered right now). The main difference between slopsquatting and typosquatting we’ve had in the past is that the variants look totally different, and with the former, there’s a higher volume of names for attackers to choose from.

For example, 8.7% of AI hallucinated Python package names turned out to be valid JavaScript packages. In this case, the model makes the right connection to a real thing, just in the wrong ecosystem. Fertile ground for attackers to register package names from other ecosystems.

Researchers at USENIX Security 2025 tested 16 models across 576,000 code samples and found that hallucinations follow predictable patterns: 38% are conflations like express-mongoose, where the model mashes two real things together, 13% are typo variants, and 51% are pure fabrications. That's a much bigger pool of squattable names than typosquatting ever offered, and unlike typosquatting, none of these new names have anything to be "similar to" in npm's protection system.

Is slopsquatting happening now?

We think so. We're seeing malware packages whose names are consistent with slopsquatting pattern, but we can’t prove what the attackers intend with the names. Take unused-imports, the confirmed malicious package that we talked about earlier. As of early February, it was still pulling 233 downloads a week. Those developers are either following AI recommendations that are still pointing at this name, have it somewhere in their dependency tree and are reinstalling it, or found it in the docs or Stack Overflow that haven't been updated.

However, researchers are definitely finding and proving the first precursors of slopsquatting in real life. In early 2024, Bar Lanyado of Lasso Security noticed AI models repeatedly hallucinating a Python package called huggingface-cli. The real tool installs differently, as pip install -U "huggingface_hub[cli]", but models kept suggesting the shorter, non-existent version. Lanyado uploaded an empty package under that name to PyPI to see what would happen.

huggingface-cli got more than 30,000 authentic downloads in three months. Alibaba had copy-pasted the hallucinated install command into the README of one of their public repositories. The package was harmless, but Lanyado proved this strategy works. Alibaba is just lucky Lanyado figured it out before an attacker did.

An AI package hallucination that spread on its own

Charlie Eriksen, Security Researcher at Aikido found something even more wild– a hallucinated package name spreading through real AI infrastructure, with real agents trying to execute it, that nobody planted deliberately. In January 2026, Charlie claimed this npm package called react-codeshift. The package wasn’t real, had no author, and definitely hadn’t been registered before. The name is a classic hallucination-by-conflation. Two real packages with similar names exist, jscodeshift and react-codemod, which an LLM mashed together to invent the name react-codeshift.

The package had made its first appearance in a single commit of 47 LLM-generated Agent Skills. We can guess that an AI was asked to generate a set of coding agent instructions, and in doing so, hallucinated package names it would need to carry out those tasks. No human reviewed the output (or at least didn’t test it), so this AI hallucination was immortalized via GitHub.

By the time Charlie had found it as part of his research on unclaimed packages, this non-existent package’s name had spread to 237 repositories through forks and been translated into Japanese. After Charlie claimed it, react-codeshift kept getting a couple of daily downloads. Those are AI agents following skill instructions and triggering npx installs in real environments. If an attacker had registered it first, there could have been a larger slopsquatting attack that spread organically

How to protect against slopsquatting attacks

Verify the publisher, not just the name

The obvious answer is to verify package names before installing, but it’s really not that simple. Download count isn't a reliable signal (we saw that malicious packages still have regular daily downloads). What actually matters is the publisher: who registered this package, when, and does that match what you'd expect from a legitimate maintainer? A package claiming to be an eslint plugin with no maintainer information and a registration date of last Tuesday is a red flag, regardless of its download numbers.

Treat autonomous package installation as a privileged operation

If you're running AI agents that can install packages without confirmation, Claude Code in bypass mode, an agentic coding setup, or CI pipelines with broad npm permissions, the verification step you'd normally do as a human is gone. The agent will just proceed if it has the authority. That's the threat model slopsquatting is built around, so scope those permissions accordingly.

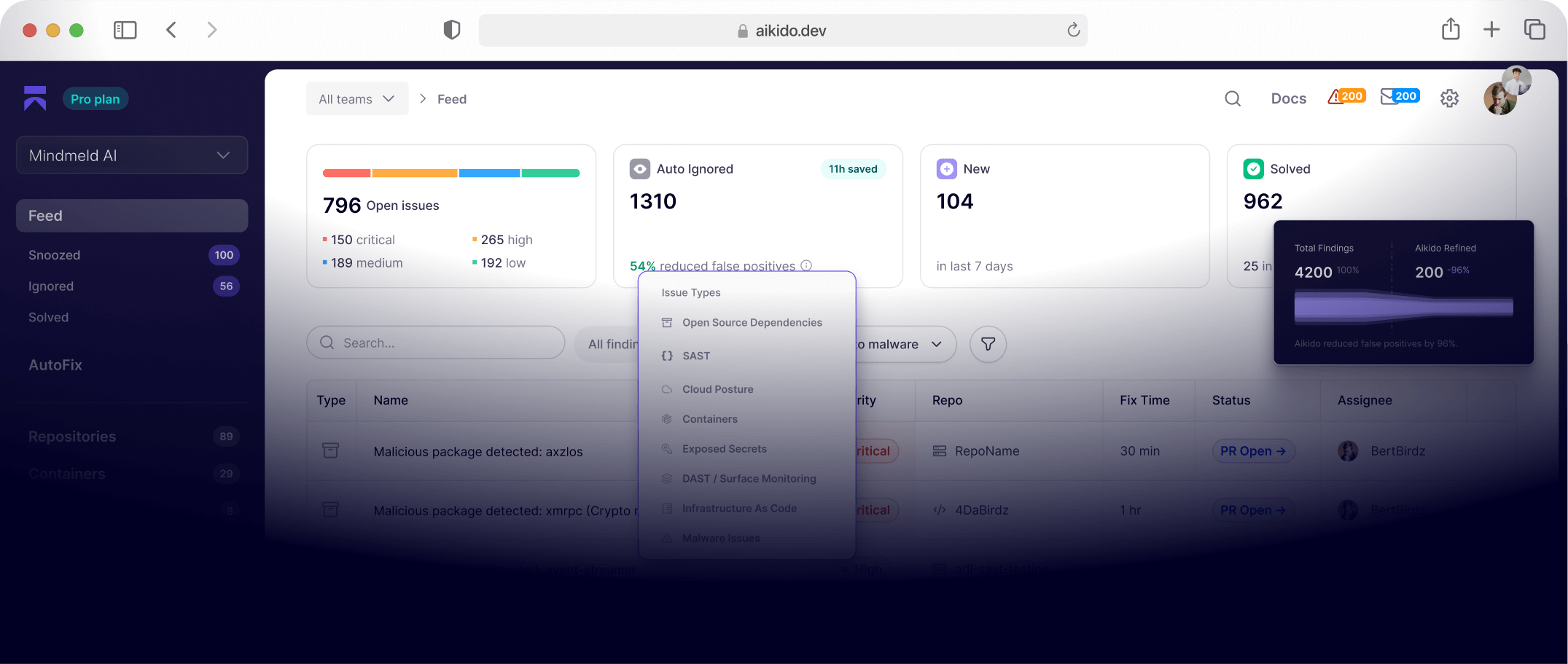

Scan your full dependency tree

Some hallucinated package names are ending up as nested dependencies rather than direct installs, which means they won't surface in your package.json. A software composition analysis (SCA) scanner looks at your full dependency tree to catch hidden, buried malicious packages.

Use SafeChain for npm-level protection

Aikido SafeChain is an open source wrapper for npm, npx, yarn, and pnpm that intercepts package install commands and checks them against Aikido Intel before anything hits your machine.

Conclusion

Unclaimed package names have always been claimable, but we now have AIs that confidently give us fake package names to install and AI agents that spread the names across repositories.

As vibe coding becomes the norm and more lobster-themed AI agents start coding with no humans around (read our piece on ‘Why trying to secure OpenClaw is ridiculous’), the window for a human to catch a bad package name before it runs keeps shrinking. We’ve seen that the names the LLMs hallucinate are consistent and repeatable, and attackers are catching on.

Check your dependency trees. Verify publishers. And use a tool that sits between your package manager and the registry and does the checking for you.