Insecure Direct Object References, commonly referred to as IDORs, remain one of the most common and damaging classes of application vulnerabilities. Despite being well documented and widely understood at a conceptual level, they continue to appear in real production systems, particularly in modern, API-driven applications.

An IDOR vulnerability occurs when an application uses a user-supplied identifier to access an internal object without verifying that the current user is authorized to access that specific object. This issue sits within the broader category of broken access control, but it is distinct in how it manifests and why it is difficult to eliminate completely.

IDORs persist not because teams are unaware of them, but because they emerge from how real systems evolve. They are often introduced at the edges of workflows, during refactors, or when ownership assumptions are reused across steps that were not originally designed to be connected. This article explains what IDORs look like in practice, why common security testing approaches struggle to detect them reliably, and how modern testing techniques validate ownership failures in running systems.

What Is an Insecure Direct Object Reference in Practice

An IDOR vulnerability occurs when an application accepts an identifier that references an internal object, such as a record, document, or account, and uses it directly without consistently enforcing authorization for that object.

Identifiers commonly appear as:

- User IDs in URL paths

- Order or invoice IDs in query parameters

- Resource identifiers in request bodies

The vulnerability is not the identifier itself. The vulnerability is the assumption that the identifier belongs to the authenticated user, without revalidating that assumption on the server.

In modern applications, this assumption often holds in most places but not all. That inconsistency is where IDORs exist.

Why IDOR Vulnerabilities Are Especially Dangerous in APIs

In API security literature, IDORs are often referred to as Broken Object Level Authorization (BOLA), the top risk in the OWASP API Security Top 10. OWASP moved to the term BOLA to fit modern API design.

APIs expose core application functionality and data. When an IDOR exists in an API, attackers can often exploit it at scale.

Common impacts include:

- Accessing sensitive data belonging to other users

- Modifying or deleting resources owned by others

- Bypassing business rules tied to ownership or role

- Undermining workflows such as approvals, billing, or account management

Because APIs are designed for automation, a single missing ownership check can compromise large portions of a system.

Common Types of IDOR Vulnerabilities

IDOR is an umbrella term. In practice, teams encounter several recurring patterns:

- Horizontal IDOR: A user accesses another user’s objects at the same privilege level

- Vertical IDOR: Identifiers allow access to privileged or administrative objects

- Blind IDOR: The response does not expose data, but the action succeeds on someone else’s object

Blind IDORs are especially easy to miss with tools that focus on obvious data exposure. They often require explicit validation to confirm impact.

How IDOR Vulnerabilities Are Traditionally Tested in Practice

During a penetration test, IDOR testing is typically performed through careful request replay and comparison.

In practice, this involves:

- Authenticating as a legitimate user

- Exercising workflows through the UI

- Capturing requests sent by the browser or client

- Replaying those requests with a different authenticated user

- Comparing responses to see whether behavior changes

For example, if a request that should only return data for User A returns the same data when replayed as User B, this indicates broken access control.

This approach is effective and widely used. It relies on the tester’s understanding of application intent and their ability to reason about which requests are security-sensitive.

However, it is also inherently manual and time-consuming. Each additional workflow, role, or state transition multiplies the number of requests that need to be captured, replayed, and interpreted. As applications grow more complex, it becomes impractical to apply this comparison exhaustively across all possible paths.

This is why manual testing often finds IDORs in areas that receive close attention, but cannot guarantee comprehensive coverage.

Why DAST Tools Miss Real IDOR Vulnerabilities

Dynamic application security testing tools operate at the request level. They crawl endpoints, fuzz inputs, and look for anomalous responses. What they do not understand is intent. A scanner does not know whether a given invoice belongs to User A or User B. It does not reason about ownership, workflow context, or whether a response is appropriate for the authenticated identity. As long as the application responds cleanly, often with a 200 OK, a scanner may treat the interaction as successful even when sensitive data is exposed to the wrong user.

This makes DAST useful for surface-level issues, but fundamentally limited when it comes to IDORs and other authorization failures that depend on object ownership and context. This limitation is not specific to any one tool. It reflects the fact that request-level scanning, even when well implemented, does not have enough context to reason about object ownership and workflow intent.

Why Static Analysis Creates Noise Around IDORs

Many teams rely on static analysis tools to flag potential IDOR issues. These tools typically look for patterns where identifiers are passed into handlers or controllers without obvious authorization checks nearby.

This often produces a large number of findings.

In practice, most of these are false positives. Authorization checks frequently exist elsewhere in the call chain, in shared middleware, or at a framework level. Static analysis cannot reliably determine whether an identifier is exploitable at runtime.

This problem is amplified when authorization is implemented implicitly or distributed across layers, including:

- Access control enforced by middleware or decorators

- Checks implemented in shared services or model methods

- Permission logic spread across multiple files and call paths

In these cases, static tools see an identifier and a data access path, but miss the full authorization context. The result is a high volume of plausible-looking findings with low confidence.

This is a fundamental limitation of static analysis. Without runtime state and identity context, no code-level analysis can reliably determine whether an object reference is exploitable in practice.

Even AI-assisted static analysis tools remain predictive. They reason about code structure, but cannot confirm runtime behavior. As a result, IDOR-like findings often carry false positive rates exceeding fifty percent, forcing teams to triage theoretical issues while real ownership failures risk being buried.

The Core Problem: Ownership Is Contextual

IDORs are not simply missing checks. They are failures of contextual authorization tied to object ownership.

Ownership is established through a combination of:

- Authentication state

- Role and permission models

- Workflow progression

- Server-side state created earlier in a process

If any part of that context is assumed rather than revalidated, an IDOR can emerge.

Some IDORs are second-order. An identifier is accepted in one step, stored, and only used later when access control is no longer checked. These issues are particularly difficult to detect because the exploit is separated across time and steps.

Testing IDORs reliably requires repeatedly asking a simple question: what happens if this identifier belongs to someone else?

UUIDs Do Not Prevent IDOR Vulnerabilities

It is a common misconception that switching from sequential identifiers to UUIDs eliminates IDOR risk.

Unpredictable identifiers reduce brute force attacks. They do not prevent unauthorized access if ownership checks are missing.

In real systems, attackers obtain identifiers through normal application behavior, including:

- References returned by other endpoints

- Shared links and URLs

- In-app messages and notifications

- Logs, exports, and browser history

If an attacker can obtain a valid identifier and the backend does not enforce ownership, an IDOR still exists.

How AI Pentesting Finds IDOR Vulnerabilities Others Miss

AI pentesting takes a different approach to identifying authorization failures.

Rather than stopping at detection, it actively tests hypotheses about ownership and access control in a running application.

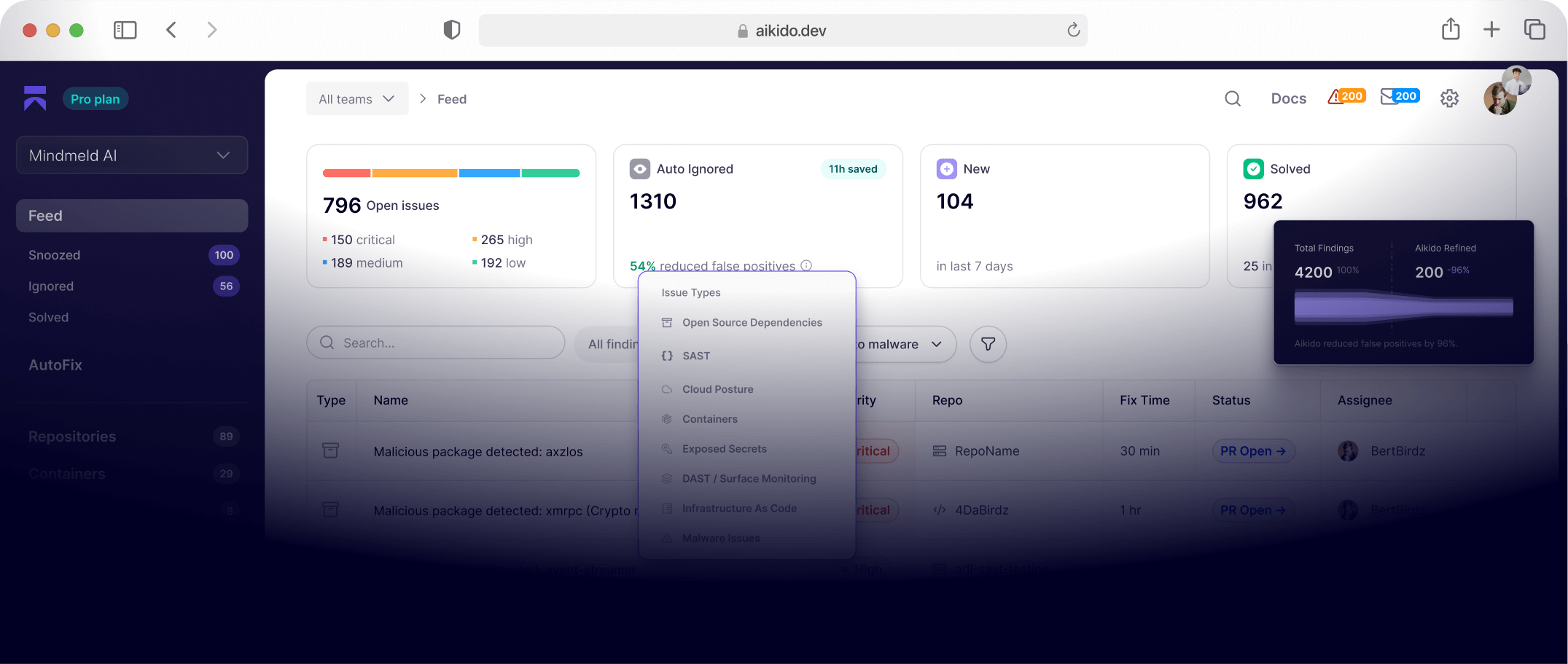

Within Aikido, this approach is implemented through Aikido Attack, autonomous penetration testing that matches human creativity with machine speed. It is.designed to evaluate authorization and ownership failures in real environments. Aikido Attack operates using real identities, exercises workflows end to end, and validates exploitability before reporting findings.

For IDORs, this process involves:

- Authenticating as real users

- Exercising full workflows end to end

- Reusing object identifiers across roles and contexts

- Attempting to access or modify resources owned by other users

- Validating whether the behavior is exploitable and reproducible

Only issues that can be exploited in practice are reported. The rest are discarded automatically.

This reduces false positives and ensures that reported findings represent real authorization failures. In situations where intent is unclear, a human tester would typically need to consult with the application owner. Runtime validation resolves this directly.

Focused Testing of Ownership Assumptions

AI pentesting allocates dedicated effort to evaluating ownership assumptions tied to object identifiers across an application.

Rather than treating IDORs as a side effect of generic testing, it explicitly focuses on:

- Identifiers bound to user-owned resources

- Workflow transitions that reuse object references

- Backend endpoints that rely on frontend ownership assumptions

This ensures consistent coverage of the parts of a system where IDORs actually occur.

Example: IDOR in a Multi-Step Approval Workflow

This example illustrates how an IDOR can emerge across multiple workflow steps even when individual endpoints appear to enforce access control correctly.

Application Context

The application includes a multi-step approval workflow for sensitive actions. A user creates a request that must later be reviewed and approved. Each request is tied to the user who created it and is referenced by an identifier used across multiple API calls.

Only the owner of a request is intended to view or modify it prior to approval.

What the System Observed

AI pentesting authenticated as a standard user and exercised the request creation flow. During this process, the system stored intermediate workflow state on the server and reused it across later steps.

Initial ownership checks were correctly enforced when the request was created.

Ownership Testing Across the Workflow

Further testing evaluated how the request identifier was used in later stages. It observed that:

- The identifier was reused when resuming a pending request

- Later API calls assumed ownership based on earlier validation

- Ownership was not revalidated when the workflow was resumed

By replaying the resume action with a different authenticated user and substituting the request identifier, the system was able to access and act on a request it did not own.

Why This Was an IDOR Vulnerability

The issue did not originate from a single missing check.

It resulted from an assumption that ownership had already been validated earlier in the workflow and did not need to be rechecked when the request was resumed. That assumption failed once object identifiers were reused across users.

Validation and Reproducibility

Before reporting the issue, the system:

- Replayed the full sequence multiple times

- Confirmed consistent behavior

- Captured evidence of unauthorized access

Only after reproducibility and impact were confirmed was the issue reported.

Why This Would Be Missed by Other Approaches

Each individual endpoint behaved correctly in isolation. The vulnerability only emerged when:

- A workflow was partially completed

- Server-side state was reused

- A later step was invoked outside the original user context

This made the issue difficult to detect through manual testing and invisible to request-based scanning tools.

Why Continuous Testing Matters for IDOR Vulnerabilities

IDORs are often introduced by change.

They commonly appear when:

- New features reuse existing data models

- Authorization logic is added in one place but not another

- Refactors unintentionally bypass earlier ownership checks

A point-in-time test may confirm that ownership is enforced today, but that assurance degrades as the application evolves.

Continuous AI-driven testing maintains confidence by re-evaluating ownership assumptions as software changes. Continuous pentesting tools support this by continuously testing new and modified workflows for unauthorized object access.

IDOR Vulnerabilities as a Symptom of System Complexity

IDORs are not edge cases. They are a natural outcome of complex systems evolving over time.

As applications grow, ownership logic spreads across services, workflows, and layers. Assumptions accumulate, and reasoning about object-level access becomes increasingly difficult.

AI pentesting does not remove this complexity, but it makes it testable.

By systematically exercising workflows, tracking state, and validating ownership in context, it turns one of the most persistent vulnerability classes into something that can be detected earlier, more consistently, and with greater confidence.

Security teams increasingly prioritize IDORs and other authorization failures because they are system-specific, regression-prone, and difficult to validate without workflow-aware, runtime testing.

You may also like: