TL:DR

IDORs are the #1 way multi-tenant SaaS companies leak data, and they’re usually discovered after deployment. Aikido Zen makes tenant isolation non-optional. Zen parses all of your SQL queries at runtime using a proper SQL parser (written in Rust), checks that every query filters on the correct tenant, and throws an error if it doesn't. Developers can no longer accidentally ship cross-tenant access. It's available today for Node.js, with Python, PHP, Go, Ruby, Java, and .NET coming soon.

Why IDORs are more dangerous now

IDOR vulnerabilities, otherwise known as Insecure Direct Object References, are one of the most common and dangerous flaws in multi-tenant applications. They happen when a query forgets to filter by tenant, letting one account access another account's data.

For a long time, IDORs were hard to catch. They didn't show up in code scans and required a lot of manual effort. Because of that, many IDOR bugs were only discovered during expensive, laborious pentests, or when security researchers found them through bug bounty programs.

But that's shifted. Agentic security testing tools can now behave like real users, clicking through workflows, switching roles and automatically trying to access resources. This makes IDOR vulnerabilities much easier to detect. But this is a double-edged sword: If these flaws are easier to find, they're also easier to exploit. This is why organizations shouldn't just be focused on detecting IDORs, but preventing them.

Why detection is not enough

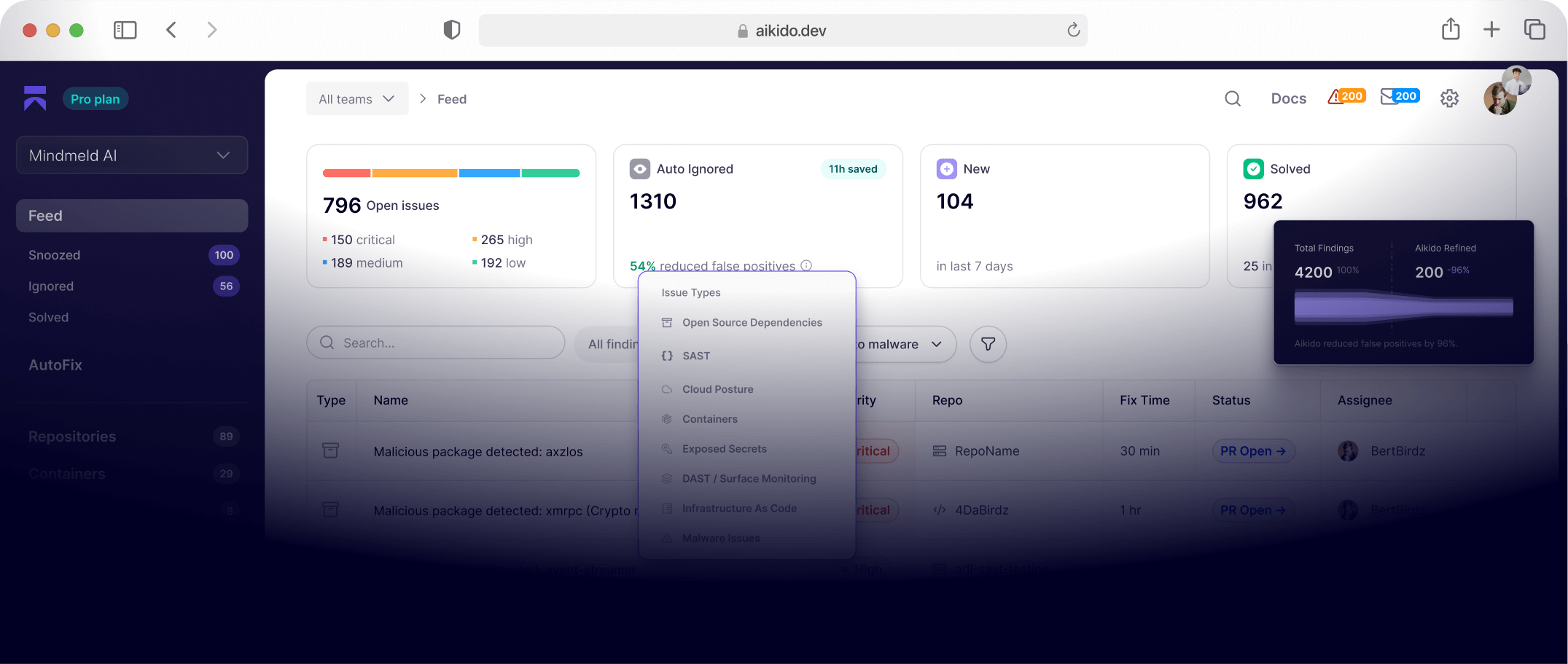

On the detection side, Aikido's AI Pentest can already find IDOR vulnerabilities, something that traditional pattern-based SAST tools could never reliably do, because IDOR requires understanding authorization context, not just code patterns. AI Pentest authenticates as real users, exercises complete workflows, and reuses object identifiers across roles to find actual exploitable IDOR flaws. It’s for this reason that many organizations that use our AI Pentest capability are predominantly interested in finding IDORs.

But finding IDOR vulnerabilities is only half the equation. In an ideal world, you'd prevent them from being introduced in the first place. That's what this post is about: IDOR protection in Zen, our open-source in-app firewall. It analyzes every SQL query at runtime and throws an error if a query is missing a tenant filter or uses the wrong tenant ID, catching the bug during development and testing before it ever reaches production.

In many enterprise environments, especially during security reviews or vendor assessments, one recurring question is how multi-tenancy is enforced and how cross-tenant data access is prevented.

Security teams and leadership want clear, technical assurances that tenant boundaries are enforced systematically, not just by convention.

Having a mechanism that automatically validates tenant scoping at the query level provides a straightforward, credible answer. It moves the conversation from "we rely on developers to remember this" to "the system enforces it automatically".

Here's what the setup looks like:

import Zen from "@aikidosec/firewall";

// 1. Tell Zen which column identifies the tenant

Zen.enableIdorProtection({

tenantColumnName: "tenant_id",

excludedTables: ["users"],

});

// 2. Set the tenant ID per request (e.g., in middleware after authentication)

app.use((req, res, next) => {

Zen.setTenantId(req.user.organizationId);

next();

});

// 3. Optionally bypass for specific queries (e.g., admin dashboards)

const result = await Zen.withoutIdorProtection(async () => {

return await db.query("SELECT count(*) FROM orders WHERE status = 'active'");

});

What does an IDOR vulnerability look like?

If your app has accounts, organizations, workspaces, or teams, you probably have a column like tenant_id that keeps each account's data separate. But when the query forgets to filter on that column, or filters on the wrong value, it means one account can access another’s data. This is an IDOR vulnerability.

Here's a simple example. You have an endpoint that returns a user's orders:

app.get("/orders/:orderId", async (req, res) => {

const order = await db.query(

"SELECT * FROM orders WHERE id = $1",

[req.params.orderId]

);

res.json(order);

});See the problem? There's no tenant_id filter. If Alice sends GET /orders/42 and order 42 belongs to Bob, Alice gets Bob's order. That's an IDOR.

The fix is straightforward, add a WHERE tenant_id = $2 clause. However, the bug is easy to introduce and hard to spot, especially in a large codebase with hundreds of queries across dozens of files. One missed filter is all it takes.

IDOR is a broad category. It also includes things like accessing other users' files via URL manipulation or API endpoints that do not check ownership. This post focuses specifically on the SQL tenant-filtering subset, making sure every database query is properly scoped to the current tenant. For a deeper dive into IDOR more broadly, check out our IDOR vulnerabilities explained post.

What's out there today

Aside from security scanning, which is more about finding existing bugs, there are other methods to prevent new IDORs from being introduced: framework-level libraries and database-level enforcement. Each has strengths and limitations.

Framework-level libraries

Several frameworks have libraries that automatically scope queries to the current tenant:

- Ruby on Rails: acts_as_tenant adds automatic tenant scoping to ActiveRecord models. Declare acts_as_tenant(:account) and all queries on that model are filtered by the current tenant.

- Django: django-multitenant does the same for Django's ORM. Set the current tenant in middleware, and Product.objects.all() automatically becomes tenant-scoped.

- Laravel: Tenancy for Laravel provides both single-database and multi-database multi-tenancy, with automatic context switching.

- .NET / EF Core: Global query filters let you apply

WHERE tenant_id = Xto every query automatically at the model level.

These libraries work well within their own ORM. The limitation is that they only protect queries that go through the ORM's abstraction. Raw SQL queries, queries from other libraries, or queries built with a different query builder in the same project will not be scoped. They're also opt-in, you have to remember to add the annotation to every model, and new models can slip through without anyone noticing. To be fair, acts_as_tenant has a require_tenant config that raises an error when no tenant is set, which mitigates the "forgot to set the tenant" risk significantly.

There are also subtle footguns. In Rails, for example, acts_as_tenant works by adding a default_scope. If a developer calls Project.unscoped to remove a different default scope, such as an archived filter, it strips all default scopes, including the tenant filter, with no error or warning. Rails has unscope (without the d) for surgically removing a single scope, but that requires knowing the tenant scope exists in the first place. In a codebase with many developers, someone will eventually reach for unscoped, and the tenant boundary silently disappears.

Database-level enforcement

PostgreSQL Row-Level Security (RLS) takes this a step further by enforcing tenant isolation at the database level. Instead of relying on your application to add WHERE tenant_id = ? to every query, you tell Postgres itself to enforce it:

-- 1. Enable RLS on each table

ALTER TABLE projects ENABLE ROW LEVEL SECURITY;

-- 2. Create a policy: only allow rows matching the session variable

CREATE POLICY tenant_isolation ON projects

FOR ALL

USING (tenant_id = current_setting('app.current_tenant_id')::uuid);

-- 3. Per request, set the tenant context before executing queries

SET app.current_tenant_id = 'aaaa-aaaa-aaaa';

-- Now even a bare SELECT only returns that tenant's rows

SELECT * FROM projects;

RLS is the strongest guarantee of the approaches listed here. Raw SQL or ORM queries, it does not matter. The database enforces it. And unlike acts_as_tenant, if you forget to set the session variable, no data is returned rather than all data. That is a much safer default.

But it comes with real trade-offs. RLS does not throw errors; queries silently return fewer rows or affect nothing. That is safer than returning all data, but it makes debugging harder. An UPDATE that should modify 100 rows might quietly affect 0 because of a policy mismatch, and it is difficult to distinguish this from "no data exists."

Connection pooling adds complexity as well. RLS with SET does not work properly with pgBouncer in statement or transaction pooling mode, which can lead to rows being returned for the wrong tenant. This may only surface in production.

There are also structural limitations. Superusers bypass all policies entirely, and views bypass RLS by default, so your app must connect as a non-superuser role. Finally, it is Postgres-only. If you need to support MySQL, SQLite for development, or another data store, your security layer does not come with you.

The pragmatic takeaway: RLS is excellent as a safety net for tenant isolation, but the operational complexity and debugging difficulty mean it is not a drop-in solution for every team.

Where Zen fits in

These are all valid approaches, and if you're using one of them, that's great. Zen's IDOR protection is designed for a different scenario: your queries go through a database driver, directly or via an ORM, and you want a safety net that works regardless of which ORM, query builder, or raw SQL pattern you use, without changing your database configuration or adopting a specific framework library.

Zen has its own trade-offs to be honest about. Like acts_as_tenant, it requires you to call setTenantId on every request. If you forget, Zen throws an error, so it fails loudly rather than silently, but it is the same class of per-request setup. And unlike RLS, Zen only covers queries that run inside your application. If someone connects to the database directly, for example through psql or a separate service without Zen, those queries are not checked.

It is also language-agnostic by design. Because the SQL analysis engine is written in Rust, we compile it to WebAssembly for Node.js and Go, and a native library that other agents call via FFI. IDOR protection specifically will be coming to the Python, PHP, Go, Ruby, Java, and .NET agents as well.

How Zen protects against IDORs

Zen sits inside your application and analyzes SQL queries at runtime, with full context about who is making the request.

A proper SQL parser, written in Rust

At the heart of Zen's IDOR protection is a real SQL parser built on the sqlparser crate in Rust, compiled to WebAssembly for Node.js and Go. It parses SQL the same way a database would by building a full Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) of your query, then walks the tree to extract:

- Which tables the query touches (including aliases)

- Which equality filters are in the WHERE clause

- Which columns and values are in INSERT statements

Why not regex? Regex works fine for simple queries like SELECT * FROM orders WHERE tenant_id = ?. But real-world applications have CTEs, UNIONs, subqueries, JOINs with aliases, and all sorts of valid SQL that a regex-based approach has trouble with. As queries get more complex, regex-based parsing becomes increasingly fragile. It is not necessarily wrong, but it is hard to maintain and easy to get surprised by.

A proper parser handles all of this out of the box. It also correctly recognizes statements that do not need checking, such as DDL statements (CREATE TABLE, ALTER TABLE), transaction control (BEGIN, COMMIT, ROLLBACK), and session commands (SET, SHOW).

Here is what the analysis looks like under the hood. Given this query:

SELECT * FROM orders

LEFT JOIN order_items ON orders.id = order_items.order_id

WHERE orders.tenant_id = $1

AND orders.status = 'active';

The parser produces:

[

{

"kind": "select",

"tables": [

{ "name": "orders" },

{ "name": "order_items" }

],

"filters": [

{ "table": "orders", "column": "tenant_id", "value": "$1" },

{ "table": "orders", "column": "status", "value": "active" }

]

}

]

Zen then checks whether every table in the query has a filter on tenant_id, and whether the filter value matches the current tenant.

The same applies to INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE. Zen makes sure the tenant column is always present and always has the right value. These are thrown as errors, not just logged. IDOR is a developer bug, not an external attack, so you want it to surface loudly during development and testing rather than slip through to production.

Performance

Parsing SQL on every query sounds expensive, but in practice it is fast. The key insight is that most applications use prepared statements or parameterized queries. The SQL string stays the same, only the parameter values change. So SELECT * FROM orders WHERE tenant_id = $1 AND status = $2 gets parsed once, and every subsequent execution of that same query is a cache hit.

The first time Zen sees a new query string, the Rust parser builds the AST and extracts the tables and filters. Every time after that, it is just a cache lookup and a comparison of the tenant ID against the resolved placeholder value.

If you are embedding values directly into SQL strings, for example string concatenation instead of parameterized queries, each unique string requires a fresh parse. But you probably should not be doing that anyway. Parameterized queries protect against SQL injection and happen to make IDOR checking fast too.

The road to production: eating our own dog food

We deployed Zen's IDOR protection on several of Aikido's own internal services. This immediately surfaced edge cases that needed handling.

Transaction support was a blocker early on. Real applications use BEGIN, COMMIT, and ROLLBACK, and Zen needed to recognize these as safe statements that do not require tenant filtering rather than erroring on them. We added this quickly after seeing it fail on our first internal deployment.

Common Table Expressions (CTEs) were another challenge. A CTE like WITH active AS (SELECT * FROM orders WHERE tenant_id = $1) creates a virtual table that downstream queries reference. Zen needed to track CTE names and exclude them from the “real table” list while still analyzing the CTE body for proper filtering.

The withoutIdorProtection escape hatch also proved essential. Not every query needs tenant filtering, such as admin dashboards, background jobs, or cross-tenant analytics. We initially tried an ignoreNextQuery approach, where you would call a function before the query to skip the check for the next SQL statement:

Zen.ignoreNextQuery();

const result = await db.query("SELECT count(*) FROM orders");

This turned out to be fragile in practice. With connection pools, the "next query" on a given connection might not be the one you intended to skip. The callback-based withoutIdorProtection is explicit about scope. IDOR protection is disabled for the duration of the callback and nothing else.

How we protected our API that serves cloud asset data

One of the services we protected early on was the internal API that serves cloud asset data across the platform.

This API is used by the UI, background jobs, and several security engines whenever they need to read information about a customer’s infrastructure. It sits at the core of the system and handles thousands of requests per second.

Because the platform is fully multi-tenant, strict tenant isolation is critical. Every query must be scoped to the correct organization, and we cannot rely on developers remembering to add the right filter in every code path.

Before Zen supported IDOR protection natively, we had a custom implementation that enforced tenant scoping at the query level. Once Zen introduced first-class support for this behavior, we migrated from the homegrown solution to the built-in functionality, which is considerably less code for us to maintain.

Today, Zen automatically verifies that queries are properly scoped to the current tenant, even under heavy load. After introducing Zen’s IDOR protection, we saw no noticeable performance impact.

Detection & prevention

Aikido's AI Pentest finds IDOR vulnerabilities in your running application by simulating real attacks. Zen's IDOR protection prevents them from being introduced in the first place by catching missing tenant filters at development time.

Together, they cover both sides. AI Pentest validates that your existing code is safe, and Zen ensures new code stays safe. Use AI Pentest to audit what is already deployed. Use Zen to catch mistakes as you write them.

Getting started

IDOR protection is available today in @aikidosec/firewall for Node.js. Check out the setup guide to get started. Support for other languages is coming soon!