Open‑source dependencies are the backbone of modern software—but they’re also a prime attack surface. Malicious actors are increasingly targeting package registries and developer workflows to inject malware that runs the moment a dependency is installed. This post explains how these supply‑chain malware campaigns work, why traditional scanners miss them, and practical defenses you can apply today.

The threat landscape: why the supply chain is a preferred target

Threat actors — including state‑sponsored groups — are actively exploiting open‑source ecosystems. Attacks range from compromised maintainer accounts to automated worms that self‑propagate across registries. The impact is amplified by how widely packages are reused: a single compromised module can be downloaded millions or billions of times across projects and organizations.

How attackers inject malware

There are several common techniques attackers use to get malicious code into your builds. Understanding these patterns makes them easier to detect and block.

- Account takeover — An attacker phishes a maintainer or steals developer tokens for registries like npm or PyPI, then publishes malware into a trusted package. When that package is installed, every consumer pulls in the malicious code.

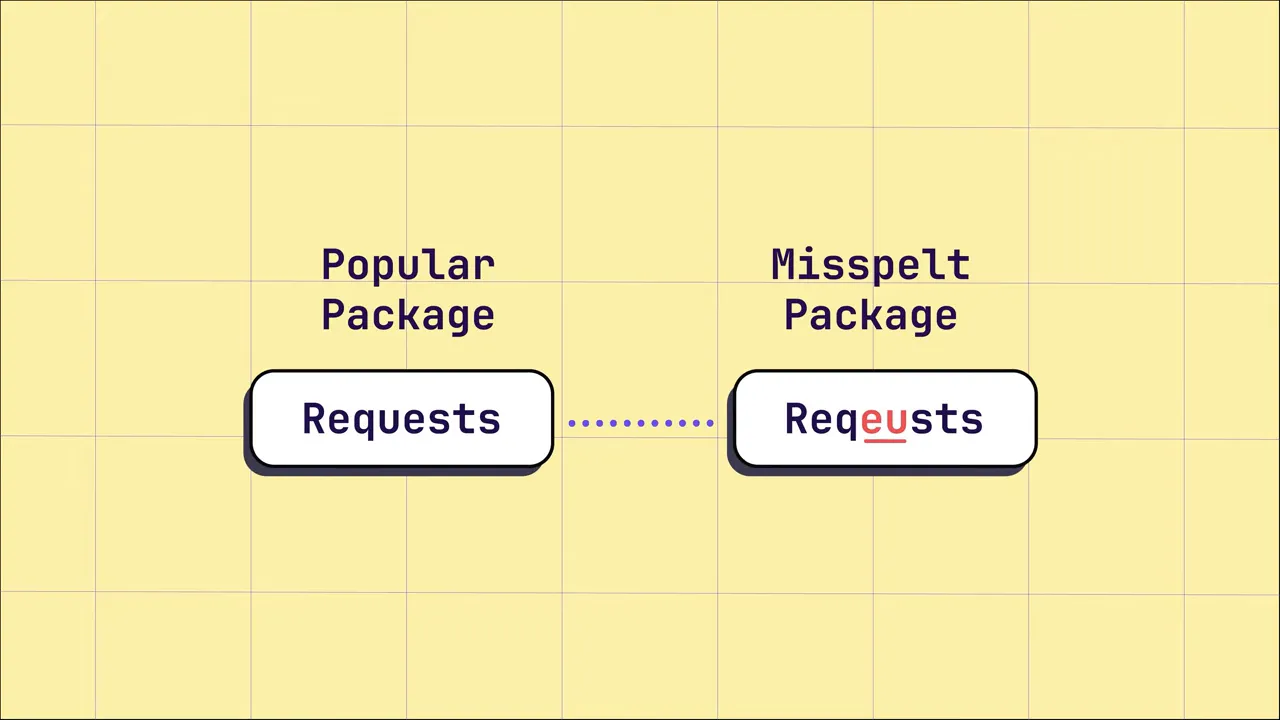

- Typo‑squatting — Adversaries publish a package with a name very similar to a popular module (e.g., CCTVX vs CCXT). A simple typo during install can mean you fetch a malicious package instead of the legitimate one.

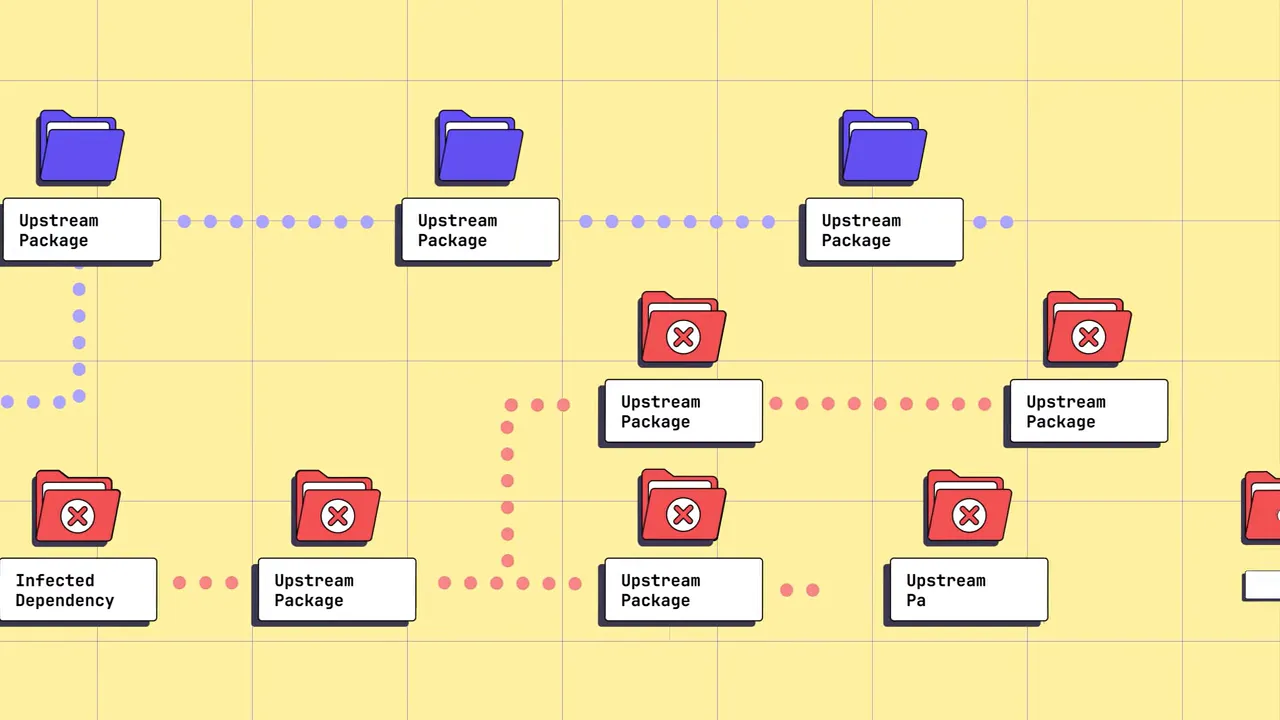

- Dependency confusion — If an internal package name is not strictly scoped to a private registry, package managers may prefer a public package with the same name. Attackers publish a public package that overrides your internal dependency.

- Hallucination squatting — Large language models sometimes invent dependencies that don’t exist. Attackers discover what LLMs tend to hallucinate, publish those invented packages, and await victims who copy generated code into projects.

Real examples that show how widespread this is

There have been high‑profile incidents where widely used packages were compromised, leading to massive exposure across the ecosystem. In other cases, self‑propagating worms stole developer tokens to automatically push the infection to more packages—turning a single compromise into an expanding campaign.

Why malware is worse than a typical vulnerability

Unlike a vulnerability that must be discovered and exploited, malware is intentionally crafted to act. Many malicious packages include pre‑install or post‑install scripts that execute immediately when the dependency is installed. Common malicious behaviors include:

- Contacting a command‑and‑control (C2) server to exfiltrate data or receive commands

- Installing backdoors or obtaining remote code execution on build systems

- Stealing package maintainer tokens to propagate across registries

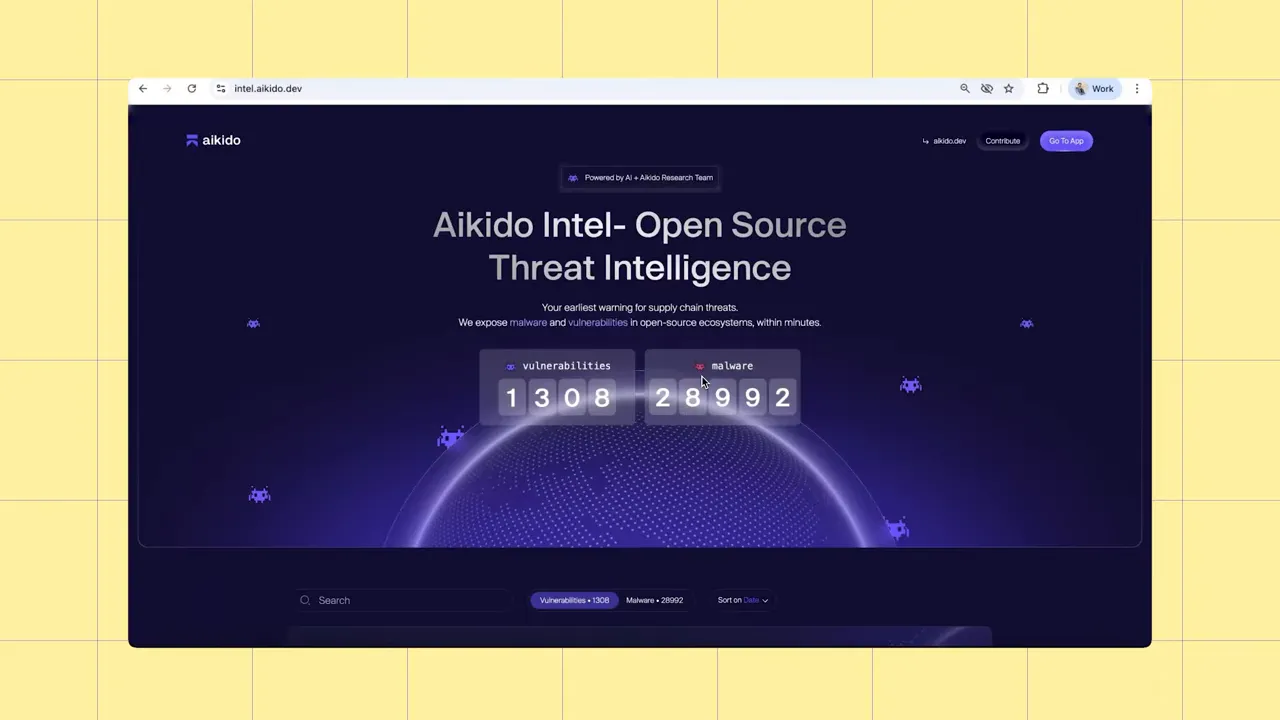

The scale: thousands of malicious packages every month

Malware in registries is not rare. Research teams monitoring registries find thousands of malicious packages each month. Most are live for only hours before takedown, which means detection needs to be fast and continuous.

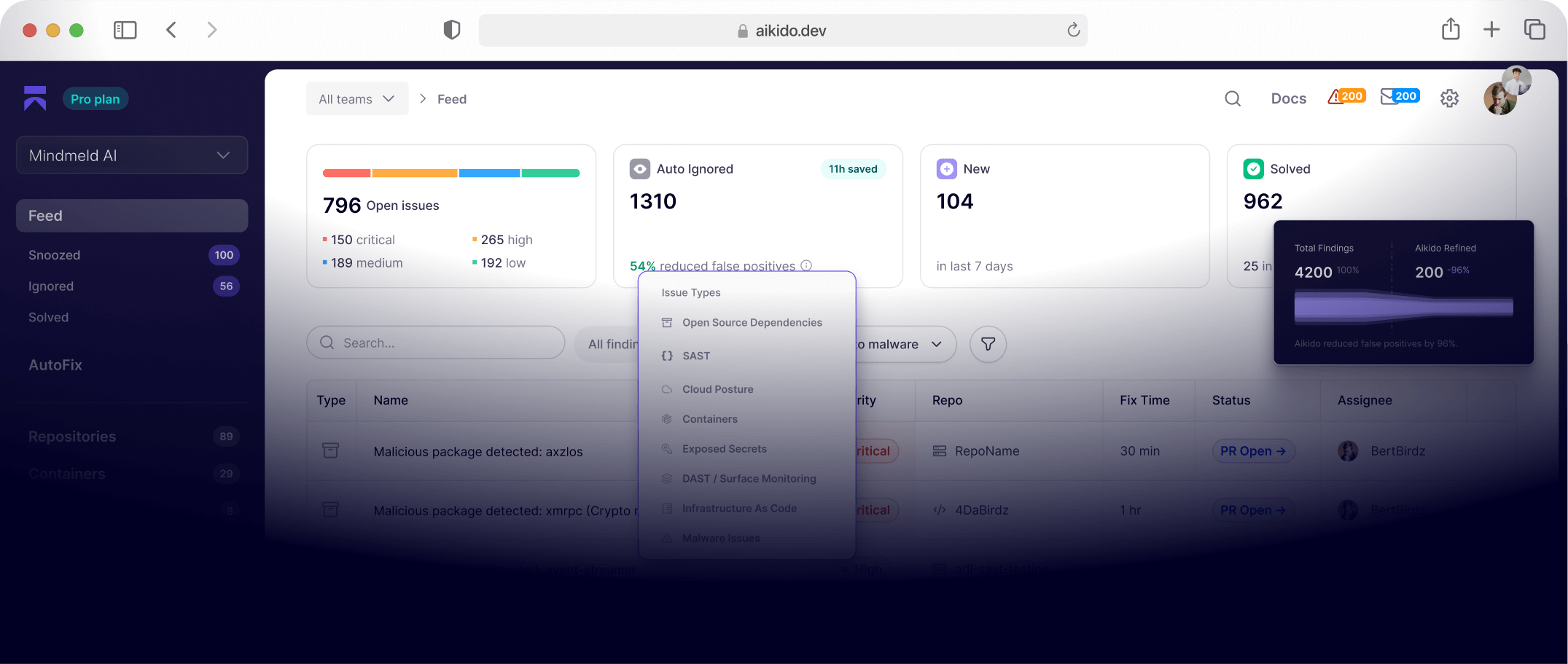

Detecting malware in real time

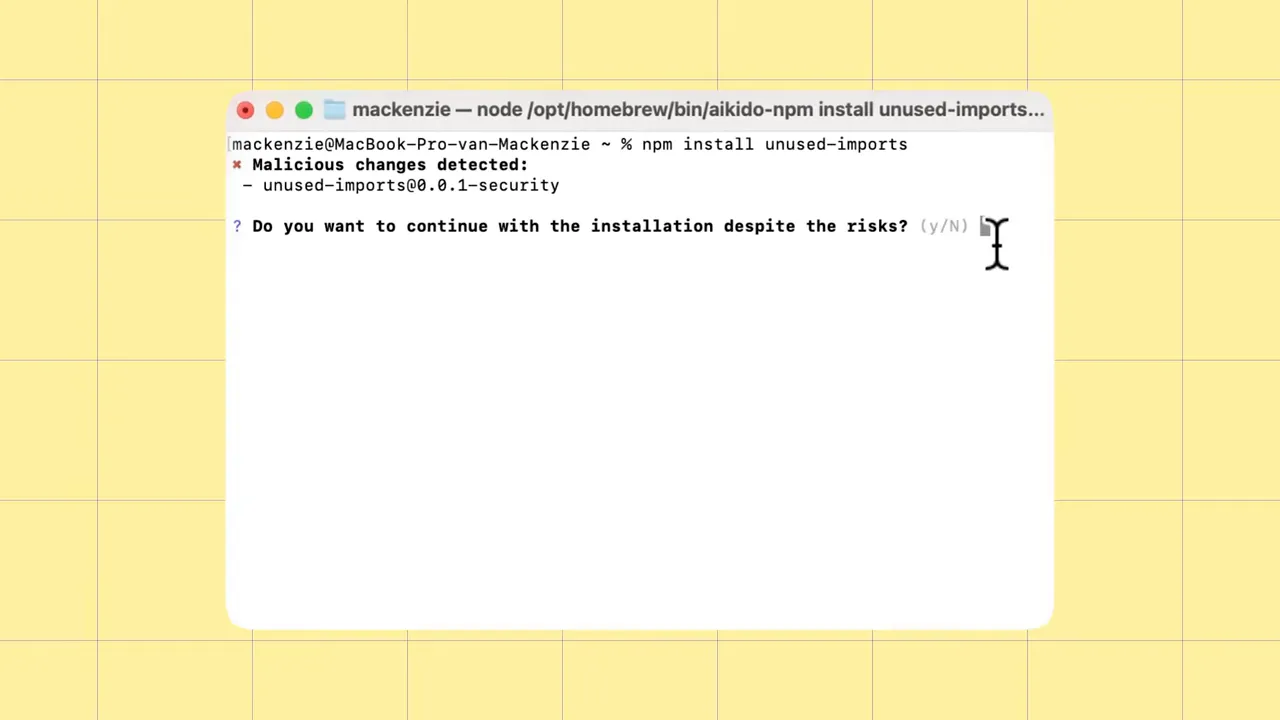

Because malicious releases can be live for a very short time window, detection tools must operate in near real time and integrate with developer workflows. Two key capabilities are essential:

- Real‑time threat intelligence — A database of malicious packages that updates continuously so installs can be checked against the latest indicators.

- Installer‑level checks — A small, low‑friction wrapper around package managers that validates packages before they are installed, without disrupting developer flow.

Tools that sit in the install path (for example wrapping npm, yarn, or pip installs) are particularly effective because they can block malware before it hits a build or a developer machine.

How threat intelligence systems spot malicious packages

Detecting supply‑chain malware is tricky because each indicator can also be benign. Examples of suspicious indicators include heavy base64 obfuscation, outbound calls to unusual domains, and invisible Unicode characters embedded in code. Any one of these flags could be legitimate.

To separate noise from true threats, modern feeds use a layered approach:

- Automated scanning for hundreds of indicators across newly published packages.

- AI or ML models that combine indicator signals to assign a probability score for maliciousness.

- Human review for medium‑risk cases, and automated takedown or blocking for high‑confidence detections.

Practical controls you can deploy today

Here are concrete steps development and security teams should take to reduce risk from supply‑chain malware:

- Enforce scoped/private registries for internal packages — Ensure internal package names cannot be confused with public packages and configure package managers to always prefer private registries for internal dependencies.

- Wrap install commands — Add an install‑time check in CI and developer machines that queries a live threat feed before allowing package installation.

- Harden developer accounts — Require multi‑factor authentication for registry accounts, rotate tokens, and monitor for suspicious logins.

- Reduce reliance on freshly published packages — Consider policies that require a minimum package age for direct installs in CI to limit the impact of same‑day malicious releases.

- Integrate threat intel into your pipeline — Feed real‑time malicious package lists into CI/CD, dependency scanners, and IDE tooling to block risky packages early.

- Train for AI hallucinations — Treat dependencies suggested by code generation tools as untrusted until verified; avoid blindly copying generated package names into manifests.

Closing thoughts

Supply‑chain malware is an active, evolving threat. It exploits both human errors (phishing, typos) and automation (registry behavior, LLM hallucinations). Combating it requires real‑time threat intelligence, tooling that integrates into normal developer workflows, and basic hygiene like scoped registries and MFA for maintainers.

Detecting and blocking malicious packages before they execute protects not only your codebase but also the broader open‑source ecosystem. Make detection fast, integrate it into installs, and treat every new dependency as untrusted until verified.

“Malware in the supply chain acts immediately—your defenses must act faster.”

Try out Aikido Security today!