We’ve all been there: you send an API request, wait for the response, and boom, you get hit with the “CORS error” pops up in your browser console.

For many developers, the first instinct is to find a quick fix: add Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * and move on. However, that approach misses the point entirely. CORS isn’t just another configuration hurdle, but one of the most important browser security mechanisms ever built.

CORS, or Cross-Origin Resource Sharing, exists to protect users while allowing legitimate cross-domain communication between web applications. Yet, it’s often misunderstood, misconfigured, or treated like a bug to “bypass.”

But not anymore.

In this guide, we’ll go beyond the basics. You’ll learn:

- Why CORS exists and how it evolved from the Same-Origin Policy (SOP)

- How browsers and servers actually negotiate cross-origin access

- What makes some CORS setups fail, even when they “look right”

- How to handle preflight requests, credentials, and browser quirks securely

By the end, you won’t just know how to configure CORS, but also, you’ll understand why it behaves the way it does and how to design your APIs around it securely.

What Is CORS (and Why It Exists)

CORS is a browser security standard that defines how web applications from one origin can safely access resources from another.

To understand CORS security, you first need to know why it was created.

Long before APIs and microservices took over the web, browsers followed a simple rule called the Same-Origin Policy (SOP).

This policy stated that a webpage could only send and receive data from the same origin, meaning the same protocol, domain, and port.

For example:

This restriction made perfect sense in the early web, when most websites were monolithic. A single site hosted its front end, back end, and assets all under one domain.

But as the web evolved with APIs, microservices, and third-party integrations, this same rule became a barrier. Developers needed front-end applications to communicate with other domains, such as:

- www.example.com talking to api.example.com

- Your app connecting to a CDN or analytics endpoint

- Web clients calling third-party APIs (like Stripe or Google Maps)

The Same-Origin Policy became a wall that blocked modern, distributed architectures.

That’s where Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) came in.

Rather than removing browser restrictions altogether, CORS introduced a controlled relaxation of SOP. It created a secure way for browsers and servers to communicate across domains, safely, and only when both sides agree.

Think of it like this: SOP is a locked door that lets no one in, and CORS is the same door, but with a guest list and a bouncer checking IDs.

This balance between flexibility and protection is what makes CORS configuration critical for every modern web app.

Understanding the Same-Origin Policy (SOP)

Before we go any further into CORS configuration, it’s essential to understand its foundation: the Same-Origin Policy (SOP).

As earlier stated, SOP is the browser’s first line of defense against malicious behavior on the web. It prevents one website from freely accessing the data of another, which could expose sensitive information like cookies, authentication tokens, or personal details.

Here’s how it works in practice: when a webpage loads in your browser, it gets assigned an origin based on three elements: the protocol, host, and port:

https:// api.example.com :443

^ ^ ^

protocol host port

Two URLs are considered same-origin only if all three of these parts match. Otherwise, the browser treats them as cross-origin.

This simple rule stops harmful cross-site actions. Without it, a random site could load your online banking dashboard in an invisible frame, read your balance, and send it to an attacker, all without your consent.

In short, SOP exists to isolate content between different sites, ensuring that each origin is a self-contained security zone.

Why SOP Alone Wasn’t Enough

The Same-Origin Policy worked perfectly when websites were self-contained. But as the web evolved into an ecosystem of APIs, microservices, and distributed architectures, this strict rule became a major limitation.

Modern applications needed to:

- Call their own APIs hosted on different subdomains (app.example.com → api.example.com)

- Fetch assets from CDNs or third-party services

- Integrate with external APIs like Stripe, Firebase, or Google Maps

Under SOP, these legitimate cross-origin requests were blocked. Developers tried every workaround possible including JSONP, reverse proxies, or duplicate domains, but these fixes were either insecure or painfully complex.

That’s where CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing) changed the game.

CORS introduced a handshake system that allowed browsers and servers to negotiate trust. Instead of breaking SOP, it extended it, providing a way to securely whitelist specific origins for cross-domain communication.

How CORS Works: The Protocol-Level Flow

As earlier stated, when your browser makes a request to a different origin, it doesn’t just send it blindly. Instead, it follows a well-defined CORS protocol: a back-and-forth conversation between the browser and the server to determine if the request should be allowed.

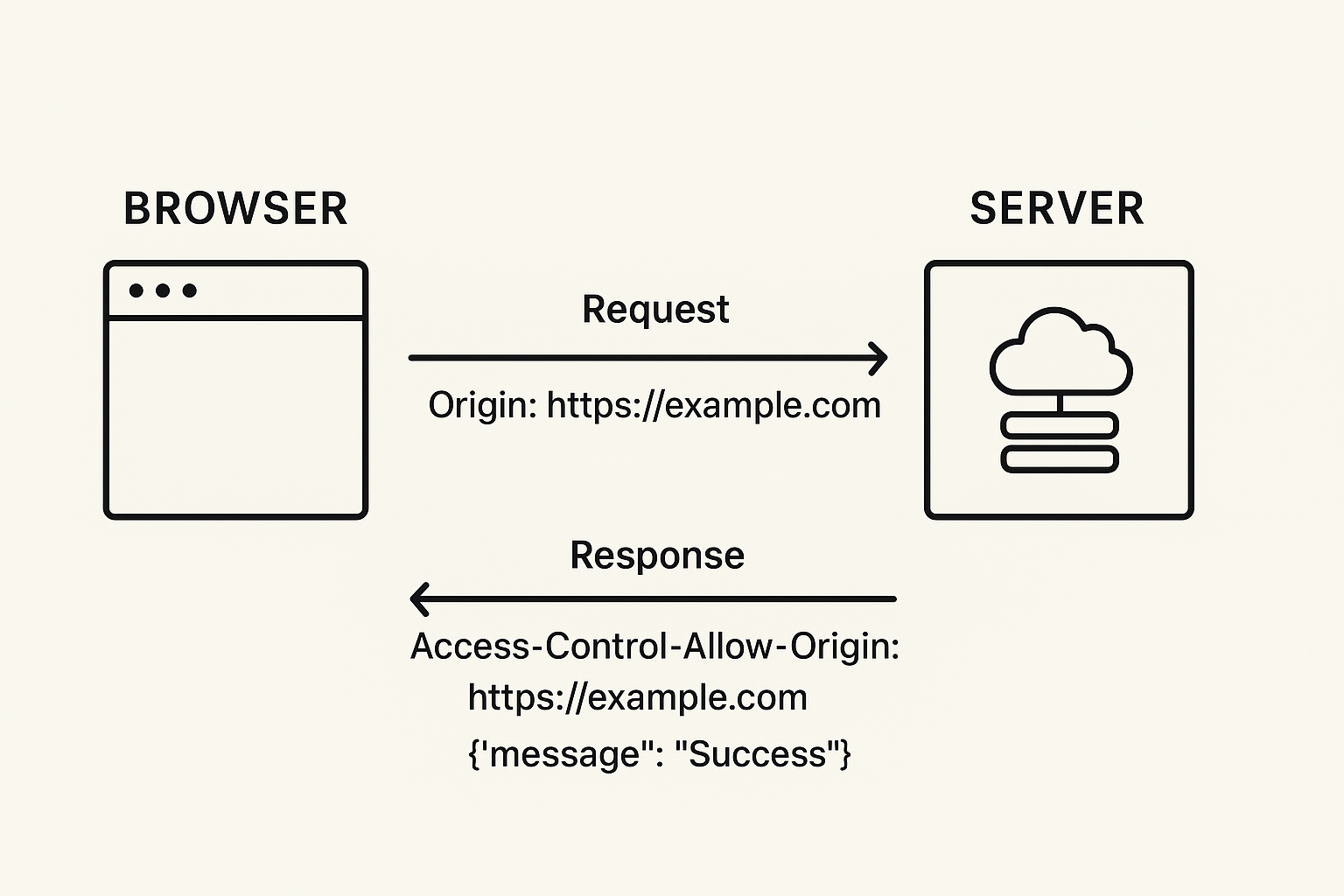

At its core, CORS works through HTTP headers. The browser attaches an Origin header to every cross-origin request, telling the server where the request is coming from. The server then responds with one or more Access-Control-* headers that define what’s allowed.

Here’s a simplified example of that conversation:

# Request

GET /api/data HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example.com

Origin: https://app.example.com

# Response

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://app.example.com

Content-Type: application/json

{"message": "Success"}

In this case, the server explicitly allows the origin https://app.example.com to access its resource. The browser checks this response, confirms the match, and delivers the data to your JavaScript.

But if the origins don’t match or if the response headers are missing or incorrect, the browser silently blocks the response. You won’t see the data, just that frustrating “CORS error” message in your console.

It’s important to note that CORS doesn’t make a server more secure by itself. Instead, it enforces rules of engagement between browsers and servers, a security layer that ensures only trusted origins can access protected resources.

Types of CORS Requests

CORS defines two main types of requests: simple and preflighted. The difference lies in how much verification the browser performs before sending data.

1. Simple Requests

A simple request is the most straightforward type. It’s automatically allowed by browsers as long as it follows specific rules:

- Uses one of these methods: GET, HEAD, or POST

- Includes only certain headers:

- Accept

- Accept-Language

- Content-Language

- Content-Type (but only application/x-www-form-urlencoded, multipart/form-data, or text/plain)

- Doesn’t use custom headers or streams

Here’s what it looks like:

# Request

GET /api/data HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example.com

Origin: https://app.example.com

# Response

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://app.example.com

Content-Type: application/json

{"message": "This is the response data"}In this case:

- The browser automatically adds the Origin header.

- The server must return Access-Control-Allow-Origin with a matching origin.

- If the origin doesn’t match or is missing, the browser blocks the response.

2. Preflight Requests

Things get more interesting with non-simple requests. For example, when you use methods like PUT, DELETE, or custom headers such as Authorization.

Before sending the actual request, the browser performs a preflight check using an OPTIONS request. This step ensures the server explicitly allows the intended operation.

Here’s an example:

# Preflight Request

OPTIONS /api/data HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example.com

Origin: https://app.example.com

Access-Control-Request-Method: PUT

Access-Control-Request-Headers: content-type, authorization

# Preflight Response

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://app.example.com

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: PUT, POST, GET, DELETE

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: content-type, authorization

Access-Control-Max-Age: 3600

# Actual Request (only sent if preflight succeeds)

PUT /api/data HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example.com

Origin: https://app.example.com

Content-Type: application/json

Authorization: Bearer token123

{"data": "update this resource"}In this sequence:

- The browser detects a non-simple request.

- It sends a preflight OPTIONS request, asking permission for the real method and headers.

- The server responds with the methods, headers, and origins it allows.

- If the preflight check passes, the browser sends the actual request. Otherwise, it blocks it.

Handling Credentials in CORS

When dealing with APIs that require authentication like cookies, tokens, or session-based logins, CORS behaves differently.

By default, browsers treat cross-origin requests as unauthenticated for security reasons. This means cookies or HTTP authentication headers aren’t included automatically.

To enable credentialed requests safely, two key steps must align:

1. The client must explicitly allow credentials:

fetch('https://api.example.com/data', {

credentials: 'include'

})2. The server must explicitly permit them:

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

But there’s a catch, and it’s a big one.

When Access-Control-Allow-Credentials is set to true, you can’t use a wildcard (*) in Access-Control-Allow-Origin. Browsers will reject the response if you try.

That’s because allowing all origins to send credentialed requests would defeat the entire purpose of CORS security, it would let any site on the internet access private data tied to a user’s session.

So instead of this:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: trueYou should always use a specific origin:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://yourapp.com

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: trueIf your API serves multiple trusted domains, you can dynamically return the correct origin header on the server side:

const allowedOrigins = ['https://app1.com', 'https://app2.com'];

const origin = req.headers.origin;

if (allowedOrigins.includes(origin)) {

res.setHeader('Access-Control-Allow-Origin', origin);

res.setHeader('Access-Control-Allow-Credentials', 'true');

}This approach ensures your authenticated requests stay secure and intentional, not open to anyone who tries.

How Browsers Determine What Requests Are CORS-Eligible

Before a request even reaches your server, the browser decides whether it falls under CORS rules.

This decision depends on the origin of the request and whether it targets another domain, port, or protocol.

For instance:

- Requesting https://api.example.com from a page served at https://example.com: ✅ CORS applies (different subdomain).

- Requesting https://example.com:3000 from https://example.com: ✅ CORS applies (different port).

- Requesting https://example.com from the same domain and port: ❌ CORS does not apply.

If the browser detects that a request crosses origins, it automatically includes the Origin header in the request:

Origin: https://example.com

This header tells the server where the request came from and it’s what the server uses to decide whether to allow or block access.

If the response lacks the right headers (like Access-Control-Allow-Origin), the browser simply blocks access to the response, even though the server technically sent one.

That’s an important distinction: the browser enforces CORS, not the server.

Internal Security Checks, XMLHttpRequest vs Fetch, and Browser Differences

Not all browsers handle CORS the same way, but they all follow the same security model: never trust cross-origin data unless explicitly allowed.

What differs is how strictly they enforce the rules and which APIs they apply them to.

1. The internal CORS security check

When a browser receives a response to a cross-origin request, it performs an internal validation step before exposing the response to your JavaScript code.

It checks for headers like:

- Access-Control-Allow-Origin: must match the requesting origin (or be * in some cases).

- Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: must be true if cookies or authentication tokens are involved.

- Access-Control-Allow-Methods and Access-Control-Allow-Headers: must match the original preflight request if one was sent.

If any of these checks fail, the browser doesn’t raise an HTTP error, it simply blocks access to the response and logs a CORS error in the console.

This makes debugging tricky, because the actual network request still succeeded, but the browser hides the result for safety.

2. XMLHttpRequest vs Fetch

Both XMLHttpRequest and the modern fetch() API support CORS, but they behave slightly differently when it comes to credentials and defaults.

With XMLHttpRequest:

- Cookies and HTTP authentication are sent automatically if withCredentials is set to true.

- Preflight behavior depends on whether custom headers are added.

With Fetch:

- Credentials (cookies, HTTP auth) are not included by default.

- You must explicitly enable them using:

fetch("https://api.example.com/data", {

credentials: "include"

});- fetch also treats redirects more strictly under CORS, because it won’t follow cross-origin redirects unless allowed.

So, while fetch is cleaner and more modern, it’s also less forgiving when you forget a header or miss a credential rule.

3. Browser differences and quirks

Even though the CORS spec is standard, browsers implement it with subtle differences:

- Safari can be overly strict with cookies and credentialed requests, especially when third-party cookies are blocked.

- Firefox sometimes caches failed preflight responses longer than expected, leading to inconsistent results during testing.

- Chrome enforces CORS on certain redirect chains more aggressively than others.

Because of these differences, a configuration that works perfectly on one browser can fail silently on another.

That’s why it’s critical to test CORS setups across browsers, especially when credentials or redirects are involved.

Server-Side Handling of the Origin Header

While the browser enforces CORS, the real decision-making happens on the server.

When the browser sends a cross-origin request, it always includes the Origin header. The server’s job is to inspect that header, decide whether to allow it, and return the correct CORS headers in response.

1. Validating the Origin

A typical request might come in like this: Origin: https://frontend.example.com

On the server, your code needs to check whether this origin is allowed. The simplest (and safest) approach is to maintain an allowlist of trusted domains:

const allowedOrigins = ["https://frontend.example.com", "https://admin.example.com"];

if (allowedOrigins.includes(req.headers.origin)) {

res.setHeader("Access-Control-Allow-Origin", req.headers.origin);

}This ensures that only known clients can access your API, while others receive no CORS permission.

Avoid returning Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * if your API handles cookies, tokens, or other credentials.

2. Handling Preflight Requests

For OPTIONS preflight requests, the server must respond with the same care as for main requests.

A complete preflight response includes:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://frontend.example.com

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET, POST, OPTIONS

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type, Authorization

Access-Control-Max-Age: 86400These headers tell the browser what’s allowed and how long it can cache that decision. If any of them are missing or incorrect, the browser will block the follow-up request even if your endpoint itself works fine.

3. Dynamically Setting CORS Headers

In large systems (like multi-tenant platforms or APIs with multiple clients), the allowed origins may need to be dynamic.

For example:

const origin = req.headers.origin;

if (origin && origin.endsWith(".trustedclient.com")) {

res.setHeader("Access-Control-Allow-Origin", origin);

}This pattern allows all subdomains of a trusted domain while still filtering out unknown sources.

Just ensure you validate origins carefully and don’t string-match on user input without constraints, or attackers could forge headers that look valid.

4. Why “It Works in Postman” Doesn’t Mean It’s Configured Correctly

One of the biggest CORS misconceptions is this: “It works in Postman, so it must be a browser issue.”

Postman doesn’t enforce CORS at all, because it’s not a browser.

That means even a completely open API with no Access-Control-* headers will respond fine there, but fail immediately in Chrome or Firefox.

So if your API works in Postman but not in your web app, your CORS headers are likely incomplete or misconfigured.

Common CORS Misconfigurations (and How to Avoid Them)

1. Using Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * with Credentials

This is the most frequent and dangerous mistake.

If your response includes both:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true…the browser will block the request automatically.

The CORS specification forbids using wildcards when credentials are included, because it would let any site access user data tied to cookies or authentication tokens.

Fix: Always return a specific origin when credentials are used:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://app.example.com

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true2. Forgetting to Handle Preflight Requests

Many APIs respond correctly to GET and POST but forget about the OPTIONS preflight request.

When that happens, the browser never reaches your actual endpoint, and it blocks the main request after the failed preflight.

Fix: Explicitly handle OPTIONS requests and respond with the right headers:

if (req.method === "OPTIONS") {

res.setHeader("Access-Control-Allow-Origin", req.headers.origin);

res.setHeader("Access-Control-Allow-Methods", "GET,POST,OPTIONS");

res.setHeader("Access-Control-Allow-Headers", "Content-Type,Authorization");

return res.sendStatus(204);

}3. Misaligned Request and Response Headers

Another subtle issue: your preflight request might ask for certain headers, but the server doesn’t explicitly allow them.

For instance, if your request includes:

Access-Control-Request-Headers: Authorization, Content-Type

…but the server only responds with:

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type

…the browser blocks it. Both lists must match exactly.

Fix: Make sure your Access-Control-Allow-Headers includes every header the client might send, especially Authorization, Accept, and custom headers.

4. Returning Multiple Access-Control-Allow-Origin Headers

Some misconfigured proxies or frameworks send multiple Access-Control-Allow-Origin headers (for example, one static * and one dynamic origin).

Browsers treat that as invalid and block the request entirely.

Fix: Always return a single, valid Access-Control-Allow-Origin header.

5. Forgetting About Method Restrictions

If you don’t include all allowed methods in Access-Control-Allow-Methods, browsers will reject legitimate requests.

For example, an API might support PUT, but your preflight response only allows GET and POST.

Fix: List every supported method or dynamically match your API routes to ensure consistency.

6. Ignoring Cached Preflight Responses

Modern browsers cache preflight results for performance.

But if your server or CDN caches responses without varying by Origin, you could accidentally send the wrong CORS headers to another client.

Fix: Use the Vary: Origin header to ensure responses are cached separately per origin.

CORS issues rarely come from one big mistake. They’re usually the result of several small mismatches between browser expectations and server configuration. Understanding these patterns helps you avoid endless “CORS error” debugging cycles.

CORS Isn’t the Enemy, Misunderstanding It Is

At first glance, CORS feels like an unnecessary barrier, or more like a gatekeeper that breaks your requests and slows development.

But in reality, it’s one of the most important browser security features ever built.

Once you understand how it works, you stop seeing “CORS errors” as random failures, but instead, they become signals that your client and server need to align better on trust, headers, or credentials.

Whether you’re building a single-page app or a distributed API ecosystem, CORS is your ally in keeping users safe while enabling secure cross-domain communication.

So the next time you hit that familiar console message, don’t reach for the wildcard. Read the headers, trace the logic, and let your understanding, and not a random hack, guide the fix!