Anthropic’s claim that Claude Opus 4.6 uncovered more than 500 previously unknown high-severity vulnerabilities in open source libraries is impressive. The more important question is how that impacts software security.

What makes Claude Opus 4.6 interesting is the way it approaches analysis. Instead of relying purely on pattern matching or brute-force fuzzing, the model reasons about code in a way closer to how experienced researchers work.

In Anthropic’s examples, Claude examined commit history to identify changes that introduce bugs, reasoned about unsafe patterns, and constructed targeted inputs to validate its findings. In other cases, it used an understanding of underlying algorithms to find edge-case code paths that fuzzers rarely exercise.

This is real progress. It suggests LLMs can contribute meaningfully to vulnerability discovery, particularly for memory corruption vulnerabilities.

The harder question is what happens once those findings leave the research environment.

Discovery Isn’t the Only Bottleneck

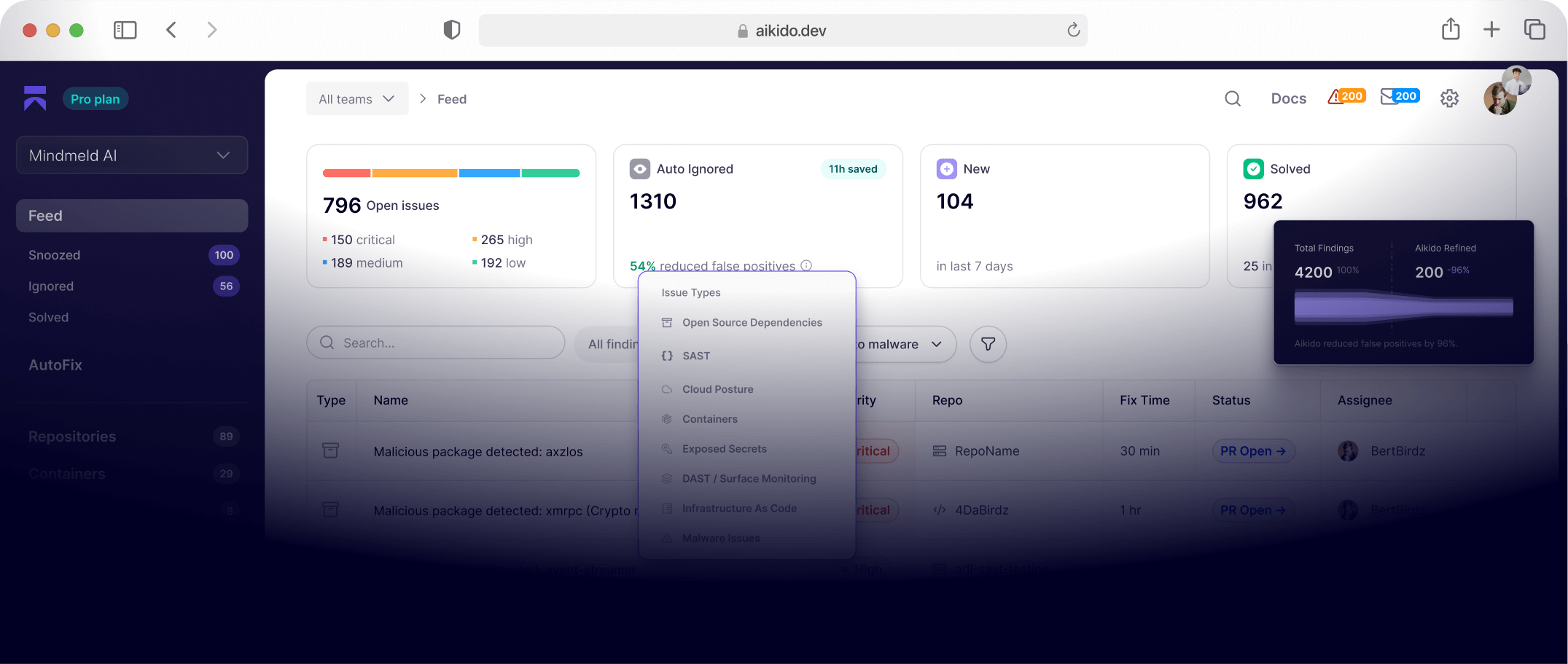

The relevant question is whether this workflow can run inside CI without introducing unacceptable noise or manual review overhead.

While quite impressive, it was a research-driven process; Claude was placed in a VM, focused on a narrow vulnerability class, and required extensive manual efforts in validation and patch writing. The process was carefully designed to reduce false positives before anything was reported.

That distinction matters because finding a vulnerability is rarely the hardest part of a security team’s job.

What teams actually struggle with are questions such as:

- Do we need to fix this now?

- Is this code path reachable in our environment?

- Is it exploitable in practice?

- Will this patch break production?

- Why did this alert appear today but not yesterday?

Those questions remain even when vulnerability discovery improves. Language models can surface potential issues, but determining impact requires system-level context.

What Actually Changes For Software Security

What actually changes with this new model is the capability of automated vulnerability discovery. LLMs can clearly reason about code paths and logic in ways traditional fuzzers struggle with. That expands the classes of bugs that can be found automatically.

What it doesn’t change is the operational burden of validation, triage, reachability analysis, regression detection, and self-remediation. Those remain system-level problems.

Why Model Upgrades Introduce Risk

Claude’s latest model may well outperform others on vulnerability discovery and reasoning, but for how long?

Some models perform better when making strict binary, yes-or-no decisions, while others handle ambiguous cases more reliably. In some cases, smaller or older models are more stable or predictable for narrow tasks, while open-weight models can be competitive in specific contexts.

There is no single model that performs best across all security use cases. Even in agentic setups where tasks are delegated across models, the problem doesn’t go away. Delegation actually increases orchestration complexity with version drift across agents, compounded error rates, and harder regression detection.

Model outputs also change between versions and different prompt contexts. Without controlled evaluation, it is difficult to detect when a model upgrade reduces detection quality or increases false positives.

If models are part of your security workflow, someone needs to continuously measure performance, compare versions, and detect when behavior changes.

This is an engineering problem that has to be solved somewhere in the stack.

Making model-driven security reliable requires controlled benchmarking, version tracking, and system-level safeguards around detection and remediation. Without that layer, improvements in model capability introduce as much variability as they remove.

While LLMs improve discovery, reliability comes from the system around them.

Reviewing Code Is Not Validating Exploitability

This distinction matters when Anthropic talks about allowing Claude to effectively write and secure itself. Anthropic describes Claude as a competent reviewer or “super tough grader” that can generate code and identify potential flaws in it.

It’s tempting to assume that a sufficiently capable generative model could validate its own output, collapsing code generation and security into a single loop without human intervention.

However, Claude’s vulnerability research highlights the limits of self-review. Reviewing code can identify unsafe patterns. It cannot confirm whether that code is reachable in production, whether it runs in your deployed version, or whether it can actually be exploited. Those answers require execution context, not just reasoning.

Security becomes reliable when detection is tied to validation in real environments. A model that reasons about source code is useful. It does not remove the need for runtime validation, reachability analysis, and controlled remediation. Reasoning improves discovery. It does not replace system-level verification.

What Actually Changes for Teams

Anthropic's work confirms that LLMs can reason about code well enough to find real vulnerabilities, including classes of bugs that traditional tools tend to miss. That capability will keep improving.

But as discovery numbers climb, the more useful question for security teams isn't how many vulnerabilities a model can find. It’s about how reliably those findings can be validated, prioritised, and acted on in the context of their own systems.

In practice, this means embedding continuous evaluation, reachability analysis, and exploitability validation directly into the security pipeline, rather than relying on raw model output. Either way, it’s interesting to see how quickly language models are developing.